A New Look at Tuition Tax Benefits

Blog Post

Nov. 3, 2015

Our new analysis, A New Look at Tuition Tax Benefits, gives the critics more reasons to be wary. It might even cause policymakers to think twice before voting to extend and expand these benefits over other types of student aid.

We used nationally representative survey data, the quadrennial National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), to estimate the optimal tax benefits undergraduates were eligible to claim, going all the way back to 1999. This differs from prior research that relies on income tax data. We show how eligibility for tax benefits is distributed among all undergraduates and how that has changed over time; the characteristics of students and families who cannot claim benefits; how eligibility and benefit amounts differ based on the type of school a student attends; and how tax benefits interact with other forms of financial aid. We also compared how tax benefit eligibility changes if the AOTC had expired by the 2011-12 school year.

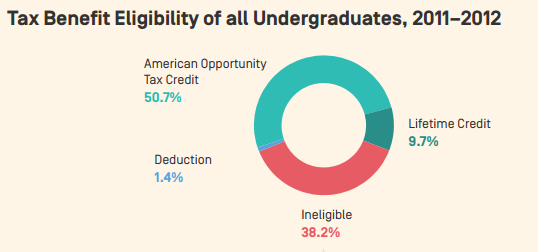

Our approach reveals surprising findings. For example, nearly 40 percent of undergraduates in the 2011-12 school year were ineligible for tuition tax benefits, but not because their incomes were too high. Rather, most of them did not pay any tuition or fee expenses net of other grants and scholarships and therefore had no qualified expenses to offset -- although they did incur living expenses that cannot be used to claim a tax benefit. Policymakers will surely be surprised to learn that the refundable feature of the AOTC did not meaningfully add to the number of students eligible for a tax benefit, and most of the benefits it did provide (55 percent) flow to students attending for-profit schools.

The analysis also uncovers a bizarre feature of federal student aid. Pell Grants generally phase out for families earning between $30,000 and $65,000, which is a perfectly acceptable way to target scarce resources. But now consider that for each $1 policymakers reduce in Pell Grant eligibility from those families, they replace it with more than $1 in tax benefits for the same families.

Lastly, the deduction for tuition and fees, which expired this year, could still be reinstated if Congress acts in the coming weeks. Our analysis shows that only 1.4 percent of undergraduates would benefit from choosing this tax benefit over one of the others. Who does that leave to claim it? The name should be appended with “for graduate students only.”

There are many more facts and figures in A New Look at Tuition Tax Benefits that are sure to change how policymakers see one of the largest sources of federal support for higher education. "