Incorporating Anti-Racist Principles into Preschool Classrooms

How educators in Oakland Unified School District are working to disrupt patterns of racism and center and celebrate BIPOC children.

Brief

Image courtesy of Sarah Jackson

April 5, 2022

Introduction: Making Schools Places of Celebration and Hope for BIPOC Children

In a webinar last April, Oakland preschool teacher Nini Humphrey told fellow educators about a boy who transferred into her classroom in the middle of the year. The young Black preschooler had been labeled “challenging” by his previous teacher and Humphrey soon understood why. He threw chairs, swore, and called the teachers names. But instead of punishing him or calling his parents to come pick him up, as previous teachers had done, Humphrey, who is also Black, did the opposite. She gave him leadership roles in her classroom. She worked to set routines and establish trust. “The transition was immense,” Humphrey said. “By the end of the year, the child was able to thrive without feeling like he was ‘the bad child.’”

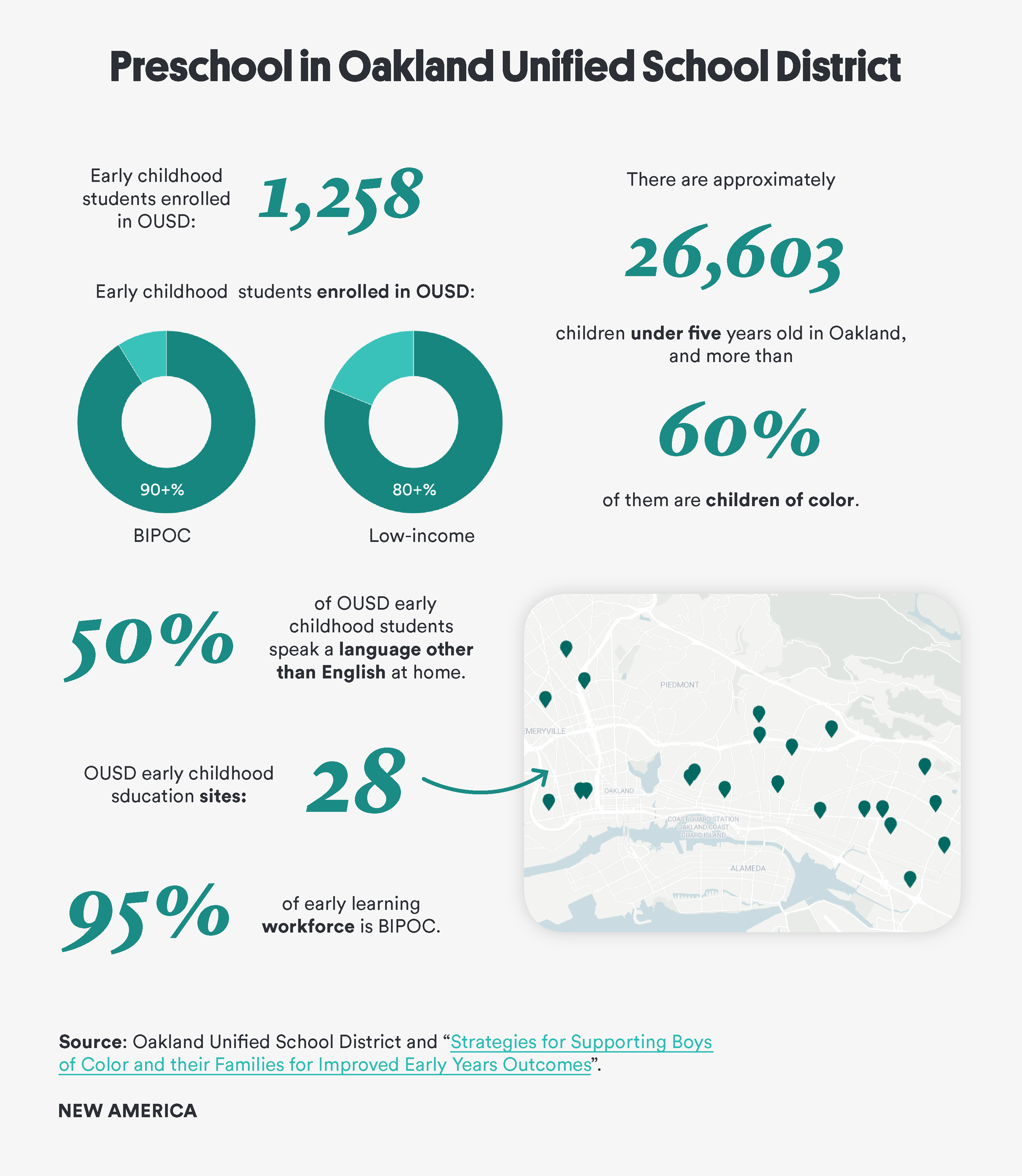

Until recently in Oakland Unified School District (OUSD), as in many places in the country, strategies like Humphrey used were too often the exception. Though the California Department of Education does not require school districts to track suspension or expulsion in preschool [1], experts say that BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) families are too often discouraged from keeping their children enrolled in state-funded preschool programs. Families are pushed out in a myriad of ways, including by educators who ask families to pick up their child early multiple times a week due to behavior challenges, suggesting that perhaps this program is not a good fit for their child or that their child's needs are beyond the support the school can offer.

These experiences, scholars say, are often the beginning of both overt and mundane racism that BIPOC children and their families experience in schools. BIPOC children are subject to surveillance and punitive discipline beginning in their early childhood years. Research has shown that young Black children specifically are disciplined at higher rates than their peers, are both over and underrepresented in the special education population, and are more likely to be chronically absent than White children.

As in many places, these have all been long-standing problems in Oakland, where the curriculum and pedagogy available to the district privileges whiteness and centers European cultural content and perspectives. Implicit and explicit bias in classrooms impacts the way BIPOC children are treated and the way they and their families experience school. This systemic racism impacts how children in Oakland see themselves as learners and their trajectory as they proceed in school.

However, since 2014, OUSD and its partners have been engaged in work to reform their early childhood systems with a focus on children and families most impacted by social and economic inequity. It is a focus that, evaluators say, is paying off.

This brief examines ongoing work in Oakland to create structures, cultures, and conditions in its schools that will disrupt patterns of racism and transform classrooms into those that center and celebrate BIPOC children. We focus on work the school district and its partners have done to incorporate anti-racist* principles in early learning settings and to change practices. Other communities and school districts can learn from Oakland’s work in four key areas: using partners and conveners; explicitly naming an approach to racial equity; working horizontally and vertically across the school district; and engaging in a racial equity audit. Collectively, these approaches disrupt the pattern and pathology that pushes out BIPOC children and work to make schools places of celebration and hope.

*All terms marked with an asterisk are defined in the glossary.

The Value of Anti-Racist Work in Early Childhood Classrooms

Research shows that how children begin their school experience can impact how they persist in school and how they finish. Families are, of course, part of the ecosystem that impacts children’s success. If the start is rocky, if children or their families feel pushed out or unsupported by the school system early in their academic careers, if they do not feel a sense of belonging or have access to high-quality early learning, children will start to disengage. Conversely, if children’s racial identity or home language is celebrated in their classroom, children feel a sense of belonging and are likely to blossom.

Taji Brown, who works in OUSD’s Office of Equity, said that too often for young Black children, their early experiences in school systems are traumatizing, isolating, and deficit-driven. BIPOC children are often labeled as troublemakers or as deficient and their families' cultural knowledge not included in the curriculum. As a result, BIPOC children can lose confidence in their ability to succeed and begin to withdraw from school.

OUSD’s Early Childhood Education Department, with the help of many partners, is working to change the culture and pedagogy in their classrooms. They aim to disrupt these deficit narratives, to create environments where BIPOC children can be celebrated and successful, and where teachers can develop trusting relationships with BIPOC children and their families.

Oakland’s Path to Decolonizing Classrooms: Collaboration, Training, and Teacher Development & Coaching

OUSD’s Early Childhood Education Department is taking a multi-pronged approach to reforming its systems and classroom practices. These include: collaboration, training, coaching, and staff development. Their goal is to be intentional about doing anti-racist work in their department throughout all of their system building and classroom practices.

Collaboration

OUSD’s Early Childhood Education Department has made collaboration a key part of its anti-racist work. Educators work closely with partners throughout the community, the school district, and within their own department.

Since 2014, OUSD has helped to develop and lead Oakland Starting Smart and Strong (OSSS), funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Oakland Starting Smart and Strong is a unique community partnership designed to build a strong early childhood system. Leadership is shared between the school district and local community-based nonprofits, philanthropy, and government.

The group’s Boys of Color workgroup recommends and supports the development of effective practices, programs, and policies for people working with young boys of color. The group runs workshops, publishes research, and has published an action toolkit that includes 10 promising practices in early learning for Black boys. The toolkit was created by education content experts along with a panel of Black male educators and practitioners.

10 Promising Practices in Early Learning for Black Boys

- “Learn about and value children’s lived experience and their families’ cultural assets.

- Implement culturally and linguistically responsive practices that represent the diversity of the boys of color in a program/school, including high-quality curriculum and instructional approaches that reflect the images and lived experiences of young boys of color.

- Build meaningful, trusting and reciprocal partnerships with families of boys of color, and include parents and caretakers in all aspects of project and program planning.

- Secure community partnerships to support boys of color and their families.

- Build educator knowledge of structural racism, oppression, power and racial equity, and how these factors disproportionately affect boys of color.

- Strengthen educators’ self-awareness of positionality (social categories of identity); their cultural values, assumptions and beliefs; and their understanding of the role that conscious and unconscious bias plays in their work with young boys of color.

- Learn and use evidence-based strategies to interrupt conscious and unconscious bias.

- Collect data to identify progress made on equity goals for Black boys and disrupt inequitable outcomes before they occur.

- Audit existing policies, procedures, and practices through a racial equity lens in order to build programs, schools, agencies, and systems that improve outcomes for boys of color.

- Use trauma-responsive, resilience building, and healing-engaged approaches and practices to inform relationship-building, policies and procedures, instruction, and communication.”

Source: Oakland Starting Smart & Strong, “10 Promising Practices in Early Learning for Boys of Color,” 2022.

New Collaborative Approach: Child Study Teams

OUSD’s Early Childhood Education Department began convening child study teams in the 2021–22 school year as a way to support educators in addressing challenging behaviors. The teams bring together administrators, special education staff, mental health professionals, and specialists like speech pathologists to help support teachers in adapting practices or classroom routines to better support individual children. Meetings are usually initiated by a teacher. The team meets once or twice for 45 minutes each and aims to provide teachers with a “think tank of specialists” to help them reflect on their instructional approaches and offer new strategies. Families often provide critical information that helps the team come up with new ways of meeting the child's need.

Typically, said Alesia Eutsler, an early learning principal with OUSD, when a teacher is concerned about a child and suspects they may have a learning difference or behavioral challenge, she makes a referral for an assessment through the District’s preschool diagnostic center. “The main difference about this approach, I think, is that the teacher is so much more directly involved,” Eutsler said. “It puts the teachers in the driver's seat.” The teacher will present briefly to the group on the child’s strengths and gifts as well as the challenges.

Eutsler said that this approach gives the teacher extra tools to help her support children and families and a brain trust to help her understand a particular child’s behavior. Because the team is not giving any kind of diagnosis, it can be convened quickly. Teachers can also—at the same time—request a more formal assessment or wait to see if that becomes necessary down the line. The approach, Eutsler said, is working. A mental health consultant can come and observe the classroom and make suggestions for the teachers, for example, without saddling the child with unnecessary diagnoses or paperwork. “It’s a beautiful model,” she said.

Training

OUSD’s strategic plan calls for educators to “resist assumptions and biases and see the gift of every student and adult.” The Early Childhood Education Department at OUSD has a professional development plan that focuses on decolonizing* its schools to center children of color and their experiences starting in preschool. The training has included adoption of a new curriculum; training in anti-racism, anti-bias, and anti-hate; book groups; culturally responsive teaching; and making sure all educators are equipped to respond to children and families through a trauma-informed lens.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, as most instruction moved online, teachers in the department had more flexibility in their schedules. The department took advantage of this time by hosting professional learning groups on Zoom and professional learning days where teachers could share experiences, unpack their own feelings about race, and discuss their pedagogic goals.

The department’s goal was to go beyond the usual diversity, equity, and inclusion models and instead to be explicitly anti-racist. Administrators aimed to help educators disrupt dominant colonial pedagogies and deficit narratives about BIPOC children and communities and move to more abolitionist teaching* strategies. These strategies, as defined by educator Bettina Love, argue for giving BIPOC children educational experiences that place BIPOC families, communities, and cultural knowledge at the center.

OUSD adopted a version of the equity framework designed by Gholdy Muhammad that includes intellect, skills, criticality, identity, and joy. The department aims to work with teachers to nurture academic excellence by centering joy as the gateway to learning based on children’s and families’ hopes, dreams, and aspirations.

The department adopted The Creative Curriculum and helped train preschool teachers to adapt content and classroom approaches in ways that affirm and mirror children’s identities. Facilitators of the training were BIPOC and representative of the educator and student community and in terms of diversity in race and language. Facilitators told teachers that the approach they take in the classroom should be anti-racist, anti-bias, and anti-hate. Facilitators and administrators worked with educators in large and small groups and individually on how to take this approach. Discussions included topics like centering joy; instructional approaches that use positive images and narratives of BIPOC children, families, and communities; and creating mirrors that reflect BIPOC children’s experiences and windows so they can peer into other people’s experiences.

Early Learning Principal Alesia Eutsler discusses her work at Yuk Yau Child Development Center in Oakland’s Chinatown. In the height of the pandemic and during the Black Lives Matter protests, one Black parent declined to have her daughter participate in a community helpers unit on the police. Eutsler discusses how the primarily Asian American staff handled this conversation and her own work and role as a White administrator.

Trauma-Informed Classroom Practice

In addition to the training in culturally responsive teaching and anti-racism, anti-bias, and anti-hate, OSSS and OUSD developed an ongoing program to support teachers with classroom-based trauma-informed practices. This work began before the pandemic and included training for educators in how to use a trauma-informed approach. In partnership with the City of Oakland Head Start, New Teacher Center, and others, OSSS and OUSD host group training, monthly professional learning communities, and classroom coaching designed to build teachers’ knowledge and skills to help children who have experienced trauma. The program also supports educators in coping with their own traumatic experiences and teaches self-care strategies.

The group training sessions focus on the emotional development of children exposed to toxic stress* as well as those experiencing trauma, how to create a healing environment, and how to support families. The training includes information about race, systemic oppression, implicit bias, and the importance of culturally responsive teaching practices.

The department brought in local trainer Julie Kurtz, founder of the Center for Optimal Brain Integration, to co-facilitate a series of training during the pandemic on healing and trauma-informed care alongside Julie Nicholson, co-founder of the Center for Equity in Early Childhood Education, and district leadership.

Organizers named the project Resilient Oakland Communities and Kids and worked to impart a strength-based approach that focuses on community resilience and leaves judgment at the door. The team also used the work of Shawn Ginwright to inform its approach. Ginwright’s work emphasizes the psychological experiences of BIPOC youth and healing from what he calls the “toxic pathologies of a racialized social caste system that placed some on the margins within a hierarchical system.”

Ginwright emphasizes the fact that because trauma is often collectively experienced in BIPOC communities, addressing it must include considering the environmental context that caused the harm in the first place. He recommends not treating trauma as an individual pathology, but instead focusing on strengthening individual and collective well-being.

Leaders in Oakland also acknowledge the fact that many educators are dealing with their own stressors and need support so they can work effectively. This became even more true during the pandemic, as BIPOC communities experienced high levels of COVID-19 related economic impact, illness, and death. “Trauma is compounded,” Oakland Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell said in a webinar in 2021. “And we've got many folks at work in our schools that are in the same community that many of our students and families are coming from.” Johnson-Trammell, who was herself raised in Oakland, said she wanted to make sure her staff had the support they needed to heal from their own pandemic trauma in order to be able to respond fully to children and families.

Teacher Development and Coaching

Early Literacy Kings

The Early Literacy Kings project is an emerging strategy in OUSD that brings young men of color, ages 18 to 24, into prekindergarten classrooms to improve literacy skills. The pilot project, situated inside OUSD’s office of African American Male Achievement, began on a very small scale just before the pandemic and is working on slowly expanding.

“Our goal,” said program manager Taji Brown, “is to make pathways for men of color to become teachers in Oakland.” Early childhood education is still widely viewed as a women’s field, and there are almost no men in the district’s early learning workforce. Research shows that BIPOC children have fewer unexcused absences and are more likely to graduate from high school and go to college when they have had a teacher of color. The program provides a higher education stipend and training in literacy instruction, in addition to hourly pay. Early Literacy Kings is too new to have rigorous evaluation results yet, but the district is committed to evaluating and improving as the program grows.

“Our goal is to make pathways for men of color to become teachers in Oakland.”

- Taji Brown, Program Manager, Early Literacy Kings

Brown emphasizes that the value of the Early Literacy Kings program is not just about academics. He is most proud of the program’s ability to help build relationships, and to help young Black boys learn to navigate the culture of school and to eventually help change that culture from within.

Recruiting, Brown said, has been challenging, partly because young Black men in Oakland do not see themselves as teachers and the pay is low. But recruiting has also been challenging because many young Black men bring their own trauma with them from their time in school, when they were assumed by the adults in charge to be troublemakers, angry, deficient, or “less than” in some way. Men describe being victims of both implicit bias and overt racism, Brown said, and are not eager to return to those environments.

But slowly, Brown said, the program is growing. And its effects have been powerful. “It shows them that you can do this,” he said. “Because I'm here. If I'm here, you can be here. It shows them that since I'm here, I've made it here. You belong. This is reachable. This is attainable.”

New Teacher Center

Oakland’s Early Childhood Education Department also has a six-year long partnership with the New Teacher Center. The effort, which has been largely foundation funded, provides coaching support to early learning teachers and leaders, much of it centered around equity. The center is piloting a new platform called Direct to Educator that pairs coaching with online content that teachers complete on their own time on topics like identity, microaggression, and culturally responsive teaching. The platform, developed by the New Teacher Center, includes reflection questions, videos, and self-directed activities.

Coaches discuss these with teachers and can help debrief, answer questions, and challenge them to think in new and different ways, according to Melissa Luc, one of the coaches in Oakland. This “deep thinking,” Luc says, is a key part of strengthening teacher practice and disrupting the “predictability of inequities” with which American students have always been faced.

One of the most important parts of anti-racist work in classrooms, says Luc, is “this inner work that we do, thinking about who we are, what our beliefs are, our experiences, recognizing our biases, and thinking about the way we show up as educators and doing something about it.”

“As a coach, I go in and I meet with teachers and talk about their life experiences,” Luc said. “I ask, ‘What made you think this?’ and ‘What kinds of biases do we walk into the classroom with?’ And, ‘How does that affect your teaching? How does it affect how you work with families?’ Things like that are not always easy to talk about, but really impactful.”

Luc says the work in classrooms and in leadership team meetings has led to some powerful conversations that will impact classroom practice and lead to a more inclusive learning environment that is supportive of all students.

Melissa Luc, a program consultant with the New Teacher Center, discusses her conversations with teachers in Oakland around race, bias, and systemic inequity in our school systems.

Conclusion & Recommendations

Data show that Oakland’s work to reform the systems that serve young children are having an impact. And, researchers say, it is likely that OUSD and its partners’ consistent focus on equity and anti-racist practice is a large part of that. A 2019 retrospective study of the Starting Smart & Strong initiative saw improvement at the student, classroom, and school levels after three years of coaching. Evaluators found that the site-based, differential coaching model led to improvements in student outcomes, teaching quality, and classroom quality for teachers who participated in coaching for three years.

“The gains that we are seeing [in Oakland] are really remarkable.”

- Erika Takada, Senior Consultant, Engage R+D

“The gains that we are seeing are really remarkable,” said Erika Takada, a senior consultant with Engage R+D and one of the authors of the study. “Observationally, Oakland has had an equity and anti-racist approach since the beginning of this initiative and, while it’s hard to disentangle the data, this has clearly been a key ingredient in the improvements we are seeing.”

There is no prescribed approach to starting this work. It is ever dynamic, evolving, and reflective of the voices of children, families, and educators who tell us the system is not working. How Oakland chose to do this work is a reflection of Oakland’s school and community context. Another early learning system may look very different, for all the reasons it should. Each school community will have different children, family, and educator demographics; thought-partners and thought-leaders; and perceptions about the role of race and racism in its history and future.

However, for school districts considering this work, we share the following four recommendations:

- Use partners and conveners. Key partners like Oakland Starting Smart & Strong centralize a system of support and collective solutions to help Oakland think about varied initiatives for the social and academic well-being of Oakland’s youngest children.

- Name your purpose and approach. Formally and explicitly name your approach to race equity in your early learning system starting with core values, educational policies, and strategic plan.

- Work horizontally and vertically. Use a parallel process whereby administrators and department leaders work alongside educators to unlearn colonial content and instructional approaches based on deficit narratives of BIPOC children and their families.

- Audit your school’s published curriculum. Engage in a race equity audit of the published curriculum adopted by your early learning program and ask how BIPOC children and families are made visible in it [2]. How are positive images and narratives of children and families reflected and celebrated?

After June 2020, at the height of the pandemic and after the murder of George Floyd, OUSD leaders saw a need for affinity spaces to help educators to do their “inner work” to help disrupt racism. As Melissa Luc described above, this inner work may, for example, mean examining one’s own biases, privileges, and the ways these may maintain the status quo of white supremacy culture* in early learning program sites and classrooms.

Affinity spaces took place as monthly gatherings for educators and anyone else who wanted to join. The groups took place on Zoom, facilitated by New Teacher Center coaches and OUSD teachers. Participants discussed, for example, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work on “intersectionality," which had been introduced previously in a department-wide professional development day, or how systems of oppression overlap to create distinct experiences for people with multiple identity categories. The spaces made room for refuge, vulnerability, bravery, and the opportunity to release both pain and joy in adopting a race equity lens in the classroom.

This is the kind of work that over time, alongside other interventions, can make a critical difference in unlearning patterns of behavior and attitudes that harm BIPOC children and families, educators and researchers say. It is the work that all spaces that serve BIPOC children and families need to spend much more time on. Centering them, using curriculum that celebrates their strengths, hiring and training educators who are from the community and who understand all there is to celebrate about this community—all of this is making a difference in building structures, cultures, and conditions that disrupt patterns of racism and transform classrooms.

Notes

[1] Preschool is defined here as any district early childhood program. The Oakland Unified School District Early Childhood Education Department administers the California State Preschool Program (CSPP) through 28 center-based early childhood sites, as well as the Transitional Kindergarten (TK) program. TK is the first year of a two-year kindergarten program available at most OUSD elementary schools.

[2] For examples of this kind of audit see The National Association for the Education of Young Children’s Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education position statement (2019) and the Culturally Responsive Curriculum Scorecard Toolkit from NYU’s Education Justice Research & Organizing Collaborative.

Additional Resources

- Center for Equity in Early Childhood Education. Co-Founders and Co-Directors LaWanda Wesley and Julie Nicholson. https://ceece.org/

- Kerry-Ann Escayg. “Anti-racism in U.S. Early Childhood Education.” Sociology Compass 14, no. 4 (April 2020). https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/soc4.12764

- Evidence Brief—Ideal Learning Environments for Young Children. Washington, DC: Trust for Learning, 2022. https://trustforlearning.org/evidence-brief/

- Shawn Ginwright. “The Future of Healing: Shifting from Trauma Informed to Healing Centered Engagement.” Medium, May 31, 2018. https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c

- Sarah Jackson. “Seeing a Birth of Hope: Training Teachers in Trauma-Informed Classroom Practice.” EdCentral (blog), New America, July 3, 2019. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/seeing-birth-hope-training-teachers-trauma-informed-classroom-practice/

- Sarah Jackson. Lessons from Three California Communities on Strengthening Early Childhood Education. Washington, DC: New America, June 25, 2018. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/lessons-three-california-communities-strengthening-early-education/

- Terry Kawi. “Decolonizing Our Classrooms Starts With Us.” PBS Teachers Lounge (blog), PBS Education, August 3rd, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/education/blog/decolonizing-our-classrooms-starts-with-us

- Bettina L. Love. We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Boston: Beacon Press, 2019.

- Gholdy Muhammad. Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. New York: Scholastic, 2020. An example of Muhammad’s equity framework that, in part, inspired our equity classroom approaches is found at https://docs.google.com/document/d/12p7UNQoGlLbECjbR4vfBj1Jaaum2nvG30zlVL3u7kEo/edit?usp=sharing

- Being Black Is Not a Risk Factor: A Strengths-Based Look at the State of the Black Child. Washington, DC: National Black Child Development Institute, 2013. https://www.nbcdi.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/Being%20Black%20Is%20Not%20a%20Risk%20Factor_0.pdf

- Julie Nicholson, Priya Shimpi Driscoll, Julie Kurtz, Doménica Márquez, LaWanda Wesley. Culturally Responsive Self-Care Practices for Early Childhood Educators. Routledge, 2020.

- Julie Nicholson, Jen Leland, Julie Kurtz, LaWanda Wesley, Sarah Nadiv. Trauma-Responsive Practices for Early Childhood Leaders. Creating and Sustaining Healing Engaged Organizations. Routledge, 2021.

- Fikile Nxumalo. Decolonizing Place in Early Childhood Education. Routledge, 2019.

- Oakland Unified School District (website). “African American Male Achievement,” welcome page. https://www.ousd.org/Page/495

- Oakland Starting Smart & Strong (website). “Promising Practices Portfolio: Nurturing Educational Joy for Young Boys of Color.” https://www.oaklandsmartandstrong.org/promisingpracticesportfolio.html

- Oakland Starting Smart & Strong (website). “BLM Event Highlights Oakland Efforts to Center Young Black Children.” April 22, 2021. https://www.oaklandsmartandstrong.org/blog/blm-event-highlights-oakland-efforts-to-center-young-black-children

- Oakland Starting Smart & Strong. “Centering Young Black Children in Oakland.” April 1, 2021. YouTube video, 1:27. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=woYZlI0rWGk

- Oakland Starting Smart & Strong (website). “Resilient Oakland Communities & Kids (ROCK): Trauma Informed Classroom Practices.” https://www.oaklandsmartandstrong.org/rock.html

- Tema Okun. “white supremacy culture.” dRworks. https://www.dismantlingracism.org

- Nadiyah Taylor. “Centering Blackness in Early Education.” Exchange, May/June 2021.

https://www.childcareexchange.com/files/2021/05/Taylor.pdf - Truss Leadership. “Dismantling White Supremacy in Schools Culture Conference.” https://culturallyresponsiveleadership.com/

- Brian L. Wright and Shelly L. Counsell. The Brilliance of Black Boys: Cultivating School Success in the Early Grades. New York: Teachers College Press, March 2018. See here.

Glossary of Terms

Anti-racist

Someone who supports an antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea.

For more see https://www.ibramxkendi.com/how-to-be-an-antiracist

Abolitionist Teaching

Teaching strategies that give BIPOC children educational experiences that place BIPOC families, communities, and cultural knowledge at the center.

For more see: https://bettinalove.com/

Decolonize

The process of deconstructing colonial ideologies that privilege White western thought and approaches over indigenous knowledge and approaches. In education and early learning, specifically, decolonization means disrupting pedagogy or curriculum that erase or essentialize Black, Brown or indigenous people and cultures.

For more see: Fikile Nuxumalo’s work here and here and here.

Toxic Stress

According to the Harvard Center for the Developing Child: “Toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship—without adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years.”

For more see: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-toxic-stress/

White Supremacy Culture

According to the National Education Association, White Supremacy Culture is “a form of racism centered upon the belief that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds and that whites should politically, economically, and socially dominate non-whites.”

For a more in-depth discussion see the following articles by Tema Okun and colleagues:

https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/

https://www.dismantlingracism.org/uploads/4/3/5/7/43579015/okun_-_white_sup_culture.pdf

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the many educators inside and outside of Oakland Unified whose work we draw on in this paper and who spent time with us: Alesia Eutsler, early learning principal; Christie Herrera, executive director of early learning, Early Childhood Education Department; Drew Giles, director of quality enhancement and professional development, Early Childhood Education Department; Taji T. Brown, program manager, Early Childhood Education and chair of the OSSS Boys of Color Workgroup; the Office of Equity, Oakland Unified School District; Melissa Luc, program consultant, New Teacher Center; Priya Jagannathan, director, Oakland Starting Smart and Strong; Clare Nolan, Erika Takada, and the team at Engage R+D; and so many others. Their work provides inspiration and a road map to a just future for all of us and our children.

We would like to thank the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for its generous support of this work. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, its officers, or its employees.