A Convenient Scapegoat for the Loan Industry

Blog Post

Oct. 20, 2008

The Bush administration and lawmakers from both political parties are continuing to look for ways to help struggling student loan providers. While students haven't experienced any problems obtaining federal loans, lenders are still having trouble coping with the turmoil in the financial markets.

Before providing any additional help, however, policymakers should take a step back and consider how we got into this mess. For years, student loan providers have relied on the asset-backed securities market to finance their loans. That market has become dysfunctional and now most lenders are only able to continue making Federal Family Education Loans with liquidity provided by the government.

The student loan industry is not completely blameless for the breakdown of investor confidence in student loans. While the greatest damage was done by mortgage lenders securitizing faulty subprime mortgage loans, student loan companies dumped plenty of high-risk private loans onto the marketplace (sometimes bundled with safer federal loans), knowing full well that some of this debt was likely to go into default.

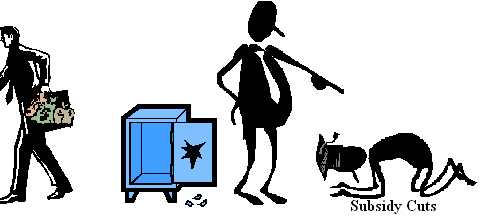

While many lenders have gratefully accepted the government's help in financing their loans, they still don't want to shoulder any responsibility for their actions. Instead, they have identified a convenient scapegoat for their problems -- the sharp cuts Congress made to lender subsidies last year. As we've noted before, the loan industry has repeatedly tried to use the panic created by the credit crunch to pressure lawmakers into revisiting the subsidy cuts.

Nowhere has this line of argument been made more openly than by Higher Education Washington Inc. (HEWI), a pro-student loan industry publication that was founded by the chief counsel to the Consumer Bankers Association. Back in March, HEWI exulted "about increasing signs that at least some in Congress will attempt to revisit the College Cost Reduction and Access Act -- specifically, the elimination of $18 billion in subsidies to private lenders." Last month, the publication took a more somber tone, noting that recent revelations about the 9.5 percent student loan scandal would "make any effort to restore liquidity to the market by restoring subsidies to lenders...that much more difficult." [It's actually pretty silly to suggest that rescinding the subsidy cuts would somehow alleviate the problems posed by such extraordinary credit markets. The size of the subsidy cuts pale in comparison to the effects that the credit crunch has had on financing costs for the student loan market.]

While the loan industry has not made much headway in these efforts on Capitol Hill, they have been pretty successful in spreading this message through the news media. Reporters almost routinely cite the subsidy cuts as one of the causes of the lenders' problems when writing about the student loan crunch. Meanwhile, the conservative editorial board of The Wall Street Journal has had a field day attacking the Democratic-led Congress for imperiling students, "What's now clear is that Congress didn't merely wring the profits out of student lending," an editorial in April stated, "It's blown up the entire student loan market." [Gee, never mind that the entire banking system has suffered as a result of the credit crunch, which The Wall Street Journal has thoroughly covered in its news pages.]

But these arguments are largely specious. Don't get us wrong. Of course, some lenders stopped participating in FFEL because of the subsidy cuts. But that was to be expected, as any reduction in subsidies will shake out the least efficient providers.

The real source of the loan industry's troubles, however, is the overall lack of available credit in the financial markets. For years, lenders financed student loans by securitizing them. Just like mortgage companies, they bundled their loans together (sometimes including both federal and private student loans) and sold them to investors to raise capital. When the securitization market froze up largely as a result of the subprime mortgage crisis, student loan providers found themselves without the money they needed to make new loans.

But don't take our word for it. In a recent report on the student loan credit crunch, the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA), a group we don't always see eye to eye with, provided one of the clearest explanations for its origins that we have seen. "The student loan crunch originated with problems in the subprime mortgage industry," the report stated, adding:

[The failure of these subprime mortgage loans] made investors extremely wary of all asset-backed securities, even extremely safe investments like student loans, which are backed by the federal government. It became exceedingly difficult for lenders to auction bundles of loans because no one wanted to purchase them. Eventually, some student loan companies had to suspend lending because they were unable to raise capital to make new loans. The inability to auction bundled loans hit non-bank student loans providers especially hard because they cannot borrow money from the Federal Reserve to make new loans. Over the past six months, dozens of for-profit and nonprofit student loan providers suspended their student loan programs or tightened eligibility requirements, limiting who can borrow from them.

See, no mention of subsidy cuts. Even a group as closely aligned with the loan industry as NASFAA has not bought into this line of argument.

NASFAA's explanation does fudge one point: the student loan industry was not an innocent bystander. Lenders dumped plenty of high-risk private loans on the marketplace and sometimes bundled them with safer federal loans. This left investors understandably wary of investing in student loans, even ones backed by the federal government.

Loan industry lobbyists don't want to look in the mirror. Instead, they are busy looking for scapegoats.

Jason Delisle contributed to this report.