Will President's Proposal Fix TEACH Grants?

Blog Post

Feb. 20, 2012

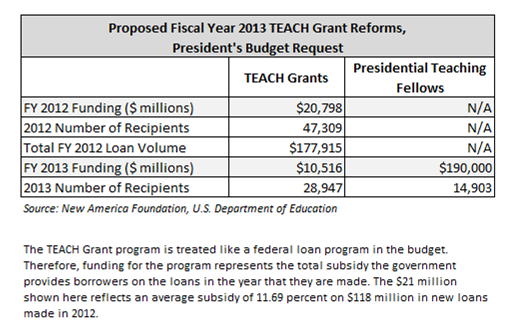

The federal government funds several programs that seek to improve the quality of teachers in low-income schools, focusing mostly on training, compensation, and evaluation. But few of these programs provide a benefit directly to teachers. The president’s budget request, released last week, would phase out and replace one such program, TEACH Grants, with a new one called Presidential Teaching Fellows. Under the proposal, the Department of Education would provide funds to states via a formula and states would then distribute the grants to students at eligible, high-quality teacher training programs. It would cost significantly more than the TEACH Grant program – mainly because the Administration expects it to be more successful (more on that below) – but it would give awards to only a third as many students.

The Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grant program, which was created by the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007, provides up to $4,000 annually in grants for full- or part-time undergraduate students (capped at $16,000) or graduate students (capped at $8,000) who agree to teach high-need subjects like mathematics and science in high-need schools. Students must maintain a 3.25 GPA to remain eligible. TEACH Grant recipients who don’t complete the full service requirement – teaching for at least four years within eight years of graduating – have to pay back their grants as loans, including interest calculated from the time the award was issued.

But TEACH Grants have a mixed record of success, which explains the administration’s efforts to replace the program (the president also included the proposal in his fiscal year 2012 budget request). According to the Department of Education, as many as three-quarters of TEACH Grant recipients do not complete their required terms of service. This means they either do not complete four years in a high-need subject at a high-need school or do not go into teaching at all. So for the vast majority of recipients, the program simply functions as another student loan program and adds to student debt.

The new Presidential Teaching Fellows program, says the Department of Education, would address a few of the root causes of the largely-unsuccessful TEACH Grants. While TEACH Grant recipients are eligible for awards in any year of their undergraduate educations, the Presidential Teaching Fellows program would be available only during their final year of an undergraduate or master’s teacher preparation program, when students are better able to commit to a specific teaching placement.

Additionally, the Presidential Teaching Fellows program reduces the service requirements for recipients to three years in a high-need subject and school within the first six years after graduation. Like TEACH Grants, the Presidential Teaching Fellows awards would still convert to a federal Unsubsidized Stafford loan should a recipient fail to complete his service requirement.

And whereas the maximum TEACH grant is $4,000 per year, the maximum annual Presidential Teaching Fellow award would be $10,000 under the president’s plan. Though the overall maximum benefit for students is lower under the president’s proposal ($10,000 for Fellows in their senior year versus $16,000 for undergraduate students receiving four years of TEACH grants), more money during that one year may provide a bigger incentive for students who need to finance their final year of their training program.

But perhaps the most powerful inspiration to replace the TEACH Grant program comes from the administration’s ongoing efforts to improve teacher and teacher-preparation programs. Under the Presidential Teaching Fellows Program, states are only eligible to participate in the program if they agree to measure the quality of teacher-preparation programs, shut down low-performing ones, and provide awards only to students at the state’s most effective teacher preparation programs. This would likely limit the number of students eligible for the program, but hopefully would also increase the number of recipients who become successful teachers.

But the Presidential Teaching Fellows program is unlikely to be an automatic slam-dunk in Congress. In an era of budget-cutting and fiscal constraints, the president has suggested replacing a program that cost $21 million in fiscal year 2012 with a new one that will cost $190 million (plus another $11 million for continued awards to 2012 TEACH recipients) in the next fiscal year. The five-year cost totals $563 million. While this new funding is meant to make a federal program work better, it’s still more spending.

The Presidential Teaching Fellows proposal would cost more than the TEACH Grant program it would replace because the Department of Education is assuming more students will complete their service requirements. That is, the administration expects that the program will be more successful in recruiting teachers to high-need schools, thereby increasing its costs. In many respects, the TEACH Grant program is really a student loan program that provides borrowers with upfront loan forgiveness that they forfeit if they do not complete the service requirement. If more students complete the service requirement, the government must provide more loan forgiveness, increasing costs. It’s also important to note that funding for both programs is outside the annual appropriations process (i.e. mandatory or entitlement funding), so the indefinitely-funded program wouldn’t compete for annual funding like most education programs.

And there is no guarantee that more Presidential Teaching Fellows would complete their full term of service than TEACH Grant recipients currently do. A shorter required term of service (albeit with a smaller overall award amount) may not be enough to recruit top students or retain them in the field. Targeting and concentrating the assistance to a student’s final year of education may not prove more effective in rewarding more committed prospective teachers, either. And while the program would require states to evaluate their teacher training programs, there is no guarantee that those evaluations will be of high quality or will result in real improvements. There is a lot of room for the White House to make its case on these arguments, if Congress ever agrees to hear them.