Young Adults in Registered Apprenticeship: What New Data Can and Cannot Tell Us

Blog Post

Source: UK Black Tech (Licensed under Creative Commons 2.0)

Sept. 20, 2022

The U.S. Registered Apprenticeship system has been proven to deliver positive outcomes for apprentices and employers alike. In an effort to make those benefits accessible to a larger, more diverse share of U.S. workers, the U.S. Department of Labor has invested heavily in strategies to expand the benefits of apprenticeship to groups who have traditionally been underrepresented in the system, namely women, people of color, and youth ages 16-24.

Last week, our partners at JFF released a timely and important analysis that found participation among this youngest cohort of apprentices has increased an incredible 113% since 2010, a sign that efforts to make apprenticeship more attractive and accessible for young adults is working. However, the brief raises valid questions about how well the system is working for them. Using data from the Registered Apprenticeship Partners Information Database System (RAPIDS), JFF finds that apprentices between the ages of 16 and 24 experience many of the same inequities that have been documented in the Registered Apprenticeship system previously, including racial and ethnic disparities in participation and occupational segregation by both race and gender, as well as the wage gaps that occur as a result.

These patterns are troubling and it’s important we address them as the apprenticeship system continues to expand. To do so, however, it’s also important to be clear about what the data can and cannot tell us: RAPIDS can provide valuable information about young adults in the Registered Apprenticeship system, but it does not provide sufficient information to draw conclusions about youth apprenticeship.

What’s the difference?

Registered Apprenticeship programs can enroll apprentices as young as 16, but they are rarely built to serve young adults, especially teens. Many require a high school diploma or GED for entry and apprentices frequently complete 30 to 40 hours of paid on-the-job training each week. As JFF’s report notes, the Registered Apprenticeship system is designed to serve adult learners. American apprentices are, on average, 29 years old.

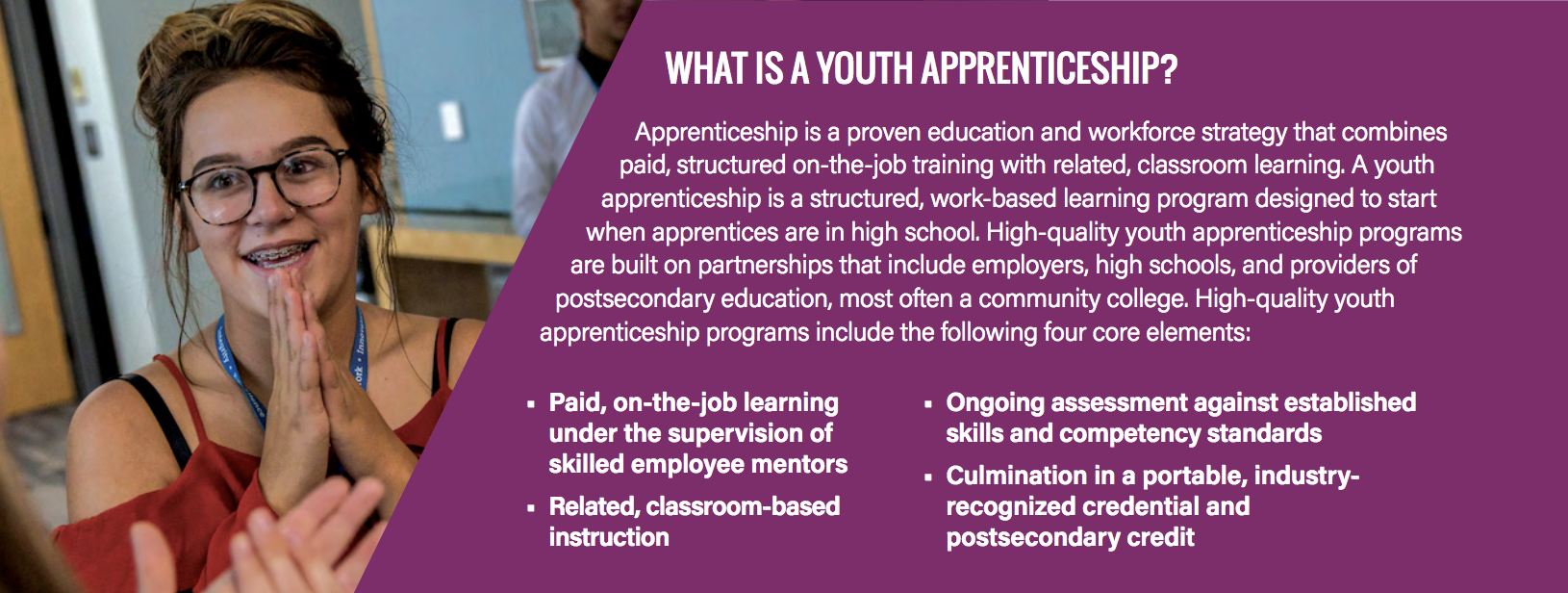

Over the last several years, however, the concept of ‘’youth apprenticeship’’ has emerged as a distinct program model that reimagines traditional apprenticeship by distributing instruction across high schools, postsecondary institutions, and employers, with the goal of creating structured, earn-and-learn pathways to affordable credentials and careers. While some of these programs are part of the Registered Apprenticeship system, many are not.

The RAPIDS system collects demographic data--age, sex, race, ethnicity, etc.--on apprentices in the Registered Apprenticeship system, as well as basic information about apprenticeship programs, including the occupations for which individual apprentices are being trained and starting and ending wages. Currently, youth apprenticeship is not defined at the federal level, and there is no indicator in the RAPIDS system that allows easy identification of programs that would be considered youth apprenticeships. So, while RAPIDS can provide information about young adults in the Registered Apprenticeship system, it cannot provide information about youth apprenticeship programs.

In 2018, New America and several national organizations, including JFF, launched the Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship, an effort to support states and cities seeking to expand apprenticeship as a deliberate equity strategy for youth. As our first collaborative action, we developed a national definition of high-quality youth apprenticeship to introduce clarity and consistency around the use of the term.

Source: Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship, 2018

Informed by months of consultation with practitioners, policymakers, and researchers, PAYA’s definition of youth apprenticeship shares key elements with the federal definition of Registered Apprenticeship, but intentionally provides flexibility around program length and duration and emphasizes credit-bearing college coursework as part of apprentices’ technical instruction as a means to promote postsecondary access and success.[1]

In addition, the PAYA National Partners developed a set of quality principles to establish guidance on the elements necessary to ensure youth apprenticeship models are designed to meet the learning needs of young adults—and especially to guard against inequities we know exist in education, the apprenticeship system, and the labor market.

PAYA’s definition and principles have influenced the development of state definitions and program models. Over the past year, we’ve seen several states grapple with how to define youth apprenticeship so it ‘’fits’’ within the Registered Apprenticeship system, while offering flexibility and support to make apprenticeship work more effectively for young adults, especially teens.

Take Virginia, where youth apprenticeship programs are called Registered Youth Apprenticeships (RYA). RYA programs meet the same criteria as adult-serving Registered Apprenticeship (RA) programs but, because they are designed to start when students are enrolled in high school, there are two key differences: (1) RYA programs can use high school Career and Technical Education (CTE) courses as part of an apprentice’s’ related technical instruction, and (2) youth apprentices’ on-the-job training can be done on a part-time basis until they graduate from high school. Once they’ve earned a high school diploma, RYAs can advance to a full-time workload and finish their coursework at a technical or community college, similar to the traditional apprenticeship model. Subtle as the differences may seem, the distinction between program models allows the state to provide a more supported, seamless pathway from high school into postsecondary education and the workforce—one that not only leverages existing education infrastructure (e.g. CTE courses), but also attends to the distinct constraints high school students face while juggling graduation requirements, technical coursework, paid work, and other realities of teenage life.

Why does it matter?

In the RAPIDS system, there is currently no way to tell if an 18-year old apprentice from Virginia is enrolled in RYA or in a traditional registered program. Even in cases where states collect data that is specific to youth apprenticeship programs--and an increasing number are attempting to do so--once that data rolls up into RAPIDS, the distinction is lost.

As a result, we can't know how many of the 40,000+ young adults in the Registered Apprentice system in 2020 were in youth apprenticeship programs. Complicating matters further, it is also difficult to know how many youth apprenticeship programs are operating outside of the registered system and missing from the data entirely.[2] As such, any attempt to use RAPIDS data to make conclusive statements about youth apprenticeship as a model is problematic.

But the fact that we cannot is equally so. Without it, we won't know if new models designed to better serve youth (and recent public investments to support those models) are yielding better, more equitable results for this fast-growing cohort within the Registered Apprenticeship system.

Is there better data elsewhere on youth apprenticeship?

States including Delaware, Michigan, and Maryland are beginning to collect and report information on youth apprenticeship programs, and many local and regional programs collect their own data, too. Though enrollment in most youth apprenticeship programs remains small, early results suggest that they can attract and support a diverse pool of young adults, when they are intentionally designed to do so. The Charleston Regional Youth Apprenticeship Program in South Carolina, led by Trident Technical College, is one example: of the 535 students that have entered the program’s registered youth apprenticeship pathways to date, 45% have been non-White and 37% have been female.[3] Likewise, CareerWise Colorado’s most recent cohort of youth apprentices is 66% female, 28% male, and 2% non-binary, a designation that RAPIDS does not allow. Nearly half identify as Hispanic, while about 15% are Black or African American. Some, but not all of CareerWise Colorado’s programs are registered with the U.S. DOL.[4]

And in North Carolina, which has invested in infrastructure to support the growth of youth apprenticeship, data from Apprenticeship NC's 2020-2021 annual report shows that the breakdown of industries hiring youth apprentices looks significantly different than the breakdown of industries hiring adult apprentices, with higher shares of youth apprentices in fields like advanced manufacturing, IT, and logistics that offer good jobs and pathways for advancement.

These data are not meant to challenge the finding that young adults in the Registered Apprenticeship system, as a cohort, are facing many of the inequities that have been well-documented in the system as a whole. That is undeniable. But these data do suggest that youth apprenticeship programs, when designed to intentionally support the learning needs of young adults, are capable of disrupting some of those patterns, at least in terms of participation by race and gender, and in the industries in which young adults complete their apprenticeships. While outcomes data on youth apprenticeship programs is still emerging, early data from leading programs like these offer reason to be optimistic.

Where do we go from here?

To better understand recent the recent growth in the U.S. Registered Apprenticeship system, we need better data to identify meaningful differences between apprenticeship programs to understand if, how, and why different models produce different outcomes, and for whom. Without this information, it will be difficult to identify promising approaches and to make informed decisions about how to support or replicate them. While this is true across the Registered Apprenticeship system, when it comes to young adults, we need--at a minimum--to be able to identify youth who are in youth apprenticeship programs in federal data.

That’s easier said than done, of course. But a good first step would be to adopt clear definitions about different program models that are emerging and improve the data we collect about them at every level of the system. State and local program leaders have taken steps to build and connect systems that collect better data on youth apprenticeship. But leaving this process entirely to states could lead to a patchwork of program definitions and data, further complicating our understanding of what programs work, for whom, and why.

A federal definition of youth apprenticeship could provide needed clarity to the field, while allowing necessary flexibility for states, and paving the way for improvements in data collection and availability. This could be achieved through a regulatory process led by the U.S. Department of Labor, or legislatively, such as through a reauthorization of the National Apprenticeship Act. The National Apprenticeship Act of 2021 (H.R. 447), which was passed by the House of Representatives last year before stalling in the Senate, would require state registration agencies to compile and submit to the U.S. DOL annual reports that include performance data disaggregated by program type (i.e., apprenticeship, pre-apprenticeship, youth apprenticeship, all defined in the bill) and by participant race, ethnicity, sex, age, and barriers to employment.

This new approach would represent a huge improvement over the current system, providing more, and more useful data to inform future investments in the fast-growing Registered Apprenticeship system. Until then, we must continue to monitor the gaps and trends RAPIDS can reveal, while being mindful of its frustrating limitations as a source of information about specific program models and characteristics.

To learn more about the Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship and to find resources to support the launch and growth of high quality youth apprenticeship programs, please visit PAYA’s ‘’Our Resources’’ page.

[1] Many states use dual or concurrent enrollment funding to cover the cost of youth apprentices’ college courses, giving them a free or nearly free head start toward degrees, should they wish to continue their education as they advance in their chosen fields.

[2] It is worth pointing out that Wisconsin has had a youth apprenticeship system operating at some scale since the early 1990’s. In FY 2020-2021, the system enrolled an all-time high of 6,414 youth apprentices. However, none of these youth apprentices would appear in the RAPIDS data, because Wisconsin’s youth apprenticeship model requires fewer hours of on-the-job training and technical instruction than is typical of Registered Apprenticeship. The Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development has taken steps to build pathways that would allow youth apprentices to transition directly into Registered Apprenticeship programs, where they would receive credit for the skills and competencies earned in the high school-connected youth program.

[3] Data provided by Trident Technical College.

[4] Data provided by CareerWise Colorado.

Enjoy what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates on what’s new in Education Policy!