Tutoring Helps Adolescent English Learners in South Carolina Improve Reading Scores

Blog Post

Shutterstock

Oct. 14, 2025

The majority of students identified as English learners (ELs) enter the public education system in kindergarten. Given this fact, it may be easy to assume that most ELs are concentrated in the elementary grades, but in reality, 43 percent of EL students are enrolled in grades 6-12. Students within this age/grade range are considered adolescent ELs, and they are not a homogenous group. Some are considered newcomers which means they have been enrolled in a U.S. school for less than three years. Others have been labeled as long-term ELs (LTELs), meaning they have not been reclassified as English proficient after a certain number of years (often six or seven years).

Adolescent ELs have distinct social-emotional, linguistic, and pedagogical needs from their younger counterparts. For example, research has found that adolescent ELs are overrepresented in special education services by a rate of 3.5 times compared to their non-EL peers. And depending on their journey to the U.S. some newcomers may have experienced interruptions to their formal education. Additionally, a study by prominent EL researcher Karen Thompson found that if an EL student who entered the public school system in kindergarten, does not reclassify by the end of elementary school they “are unlikely to ever do so.” This means ELs in older grades may need more specialized support to help them acquire English proficiency.

In addition to having more complex needs, the clock counting down adolescent students’ time in the K–12 system is ticking. This means adolescent ELs have less time remaining to develop the English proficiency needed to reclassify and exit EL services, and every minute of instructional time counts. However, it is not always clear how to make the best use of this time in a way that balances both their language and academic needs.

The need to strengthen adolescent ELs literacy was an issue that Richland School District Two in Columbia, South Carolina was grappling with. In 2024, the school district partnered with Off2Class, a digital English as a Second Language (ESL) curriculum provider [1], to implement an intervention designed to improve literacy and English Language Proficiency (ELP) among its adolescent ELs. The intervention’s efficacy was tested through a cluster randomized controlled trial study, an evaluation method where groups or clusters are randomly assigned to an intervention or control group, conducted by Evergreen Analytics, LLc. Participating EL students who met a specific criteria were randomly assigned to one of two program delivery models:

- Teacher-only group (TO), where teachers delivered Off2Class’s Foundational Literacy lessons during English Language Development (ELD) classes. Eligible students were taught in a small group for 30 minutes twice a week. Students who were not participating in the study worked independently. Outside of the Foundational Literacy lesson time, all students received the usual ELD instruction.

- Tutor + Teacher intervention group (Tutor+), participated in online lessons with a professional online tutor who delivered lessons for groups of up to three students. This tutoring took place during their ELD class which allowed their teacher to monitor their behavior and engagement while they were online. When no tutoring was scheduled students received teacher-led instruction as usual. If there were students in the class not participating in the study, the teacher led instruction for them while the others worked with their tutors.

A total of 158 ELs in grades 6 through 12 with low literacy (as measured by the Reading domain on the WIDA ACCESS) across 11 schools participated in the study. Participating ELs were enrolled in an ELD class with a certified English as a Second Language teacher, and most ELD sections included students with different ELP levels. Spanish was the most prevalent language among participating students (117 students), 101 students were classified as economically disadvantaged, 24 students were also classified as having special learning need/s, and 100 of the students were newcomers.

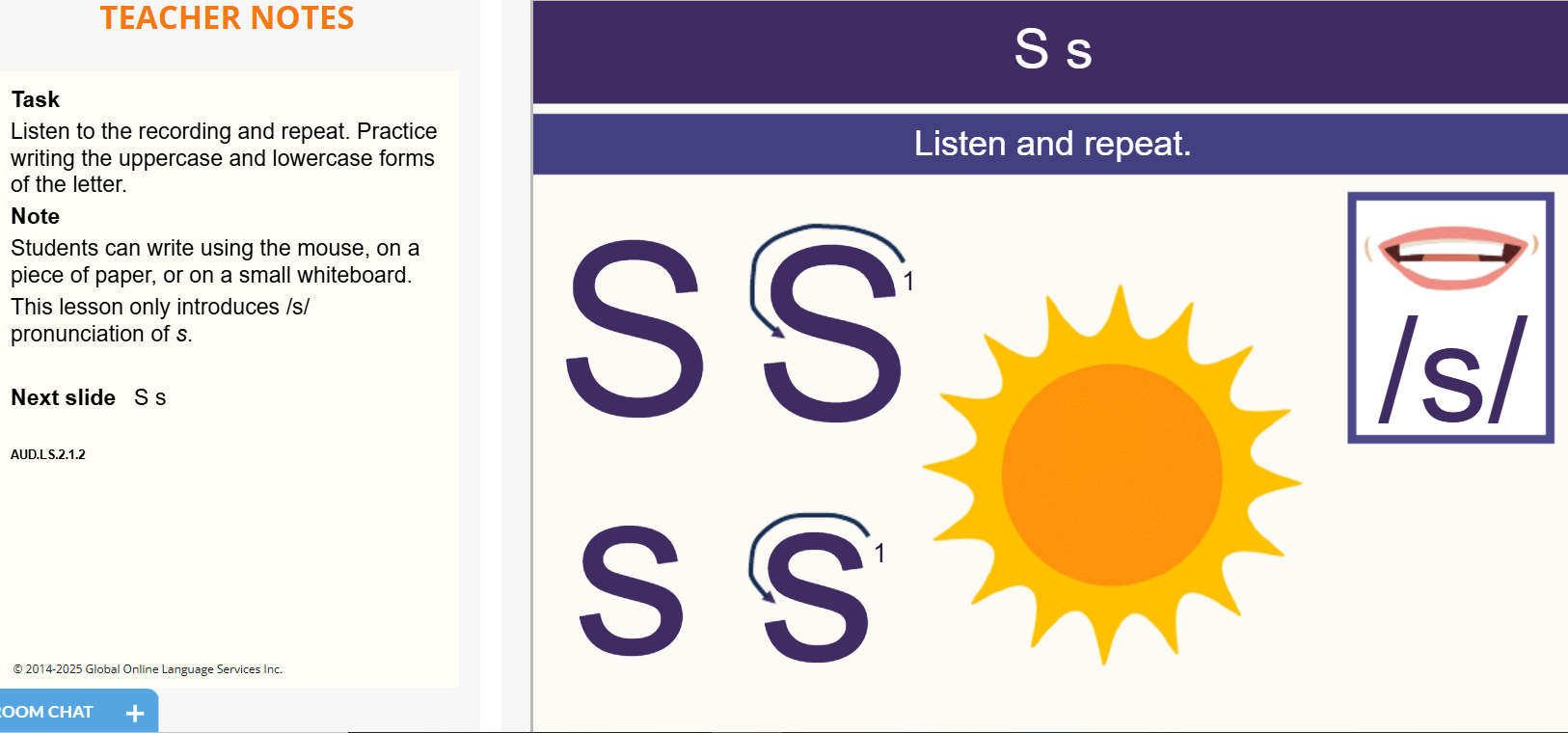

All students started with foundational literacy lessons guided by the teacher focused on explicit literacy instruction that were based on the Science of Reading and age-appropriate for adolescent learners.

Figure 1. Example of a Foundational Literacy Lesson

Source: Off2Class

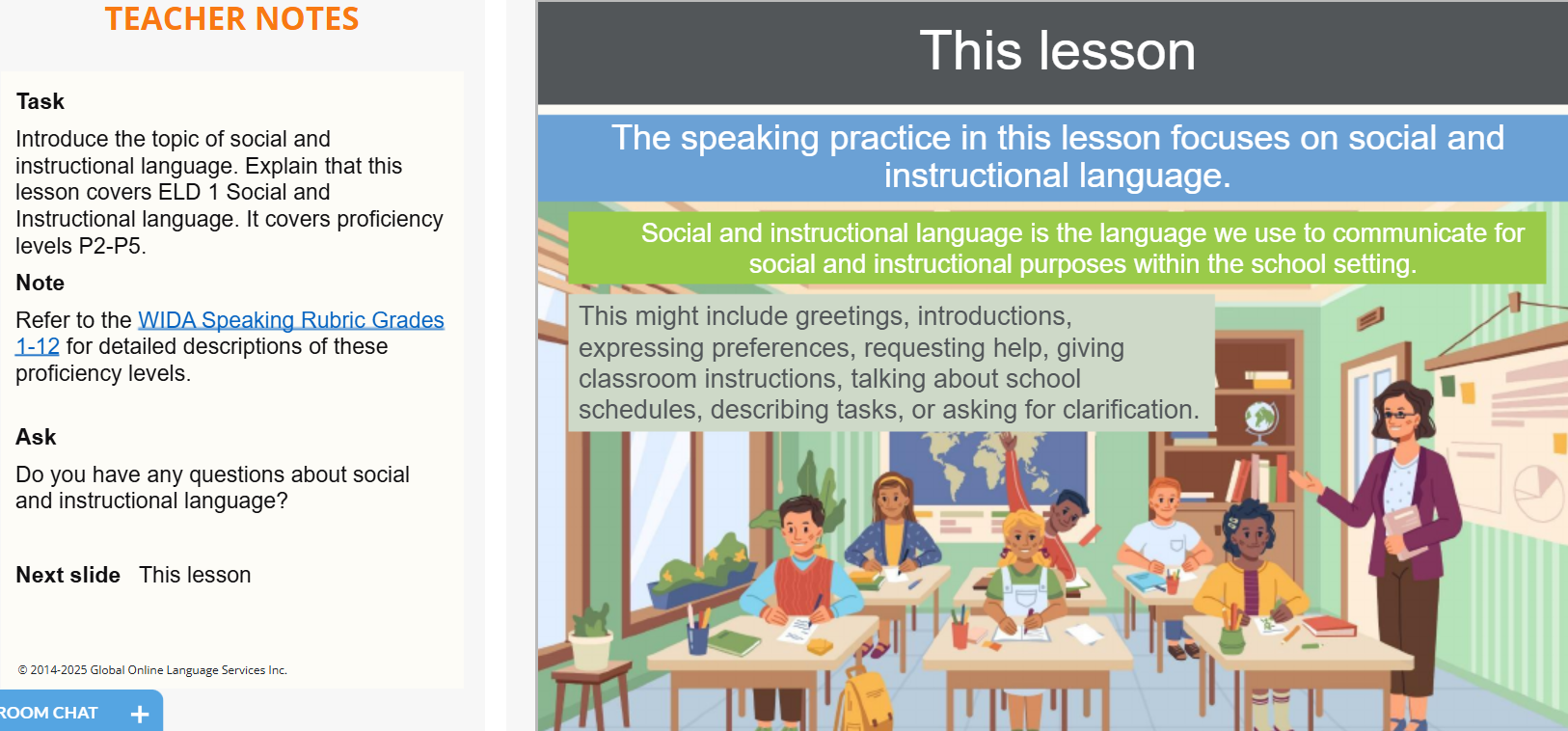

Most groups worked through these lessons and moved on to Newcomer ELD curriculum lessons focused on practicing all four language domains (reading, writing, listening, speaking), in an integrated manner with a focus on school environment vocabulary. And some groups advanced even more to WIDA practice lessons.

Figure 2. Example of Newcomer ELD Lesson

Source: Off2Class

Figure 3. Example of WIDA Prep Lesson

Source: Off2Class

Of students assigned to the Tutor + group, 77 percent advanced to content beyond the Foundational Literacy curriculum before their last lesson. Additionally, 53 percent of students received lessons that covered skills to prepare for the WIDA ACCESS assessment during tutoring sessions. On average, students covered 17 unique lesson skills in total during their tutoring sessions.

The goal was for participating ELs to receive 1,080 minutes (or 18 hours) of lessons through 30 minute lessons delivered twice a week for 18 weeks—though this target was not met. Students in the Tutor+ intervention group, received 618 minutes of tutoring on average, or about 57 percent of the intended dosage. The study found that students who received between 550 – 700 minutes of tutoring, or about 18–20 lessons experienced the largest positive effects. According to the report, busy schedules limited options for providing students with the full dosage time and rescheduling missed lessons was not always possible. Interruptions included teacher absences, school closures, emergency drills, assemblies, holidays, a conference, standardized testing days, and an e-learning day, among other reasons. Class period length also affected the amount of time available for intervention lessons. Although the intended dosage was not met, the intervention model did have a positive impact on participating ELs’ literacy scores. And

On average, participating students about doubled their expected annual ELP gains compared to national averages. More specifically, while students in both models saw their WIDA ACCESS Reading scores improve, the Tutor+ students (81 students) outpaced ELs in the TO model (77 students). High school school students performed marginally better than middle school students on the reading portion of the ACCESS. Non-economically disadvantaged students, LTELs, and students with special learning needs made higher gains than their direct counterparts as well (i.e. LTELs compared to non-LTELs, etc.).

As the authors of the study noted, the growth observed was on par with the type of improvement typically only seen among first-year newcomer students. This scale of growth is notable because the average number of years that students had been receiving EL services was five years. And according to study, the growth associated with being assigned to the Tutor+ represented about 1.2 to 1.8 years of ELP progress, based on national averages.

The estimated cost of the intervention was $104,994.16, or about $665 per EL, which is lower than the estimated costs for other high-impact tutoring programs. This estimate includes costs such as personnel, technology, and in-kind donations from the school district like staff time and building space (please see pages 31-32 of the study for a detailed expenditure table). However, this cost would have represented about one-third of funding the district typically receives from the state and Title III for ELs. (Note: this study was privately funded by Accelerate, which means the school district did not have to take on the cost of implementing the described intervention).

Previous research by Ilana M. Umansky, Karen D. Thompson, James Soland, and Amanda K. Kibler on understanding newcomer ELs’ language development needs found that the programs and services that have been shown to support robust linguistic development “may be particularly critical in middle and high schools.” Unfortunately, as the current study notes, adolescent ELs often find themselves in classes where “literacy and English language proficiency (ELP) are expected rather than explicitly taught.” This new research provides promising evidence on how personalized tutoring can help adolescent ELs build their literacy and English language skills. Future research could test the effectiveness of this intervention in different contexts, and examine the impact of the intervention on the amount of time it takes adolescent ELs’ to reclassify.

[1] This blog post provides an overview of a research study examining Off2Class and is not an endorsement of their products.