Deal or No Deal?

How Higher Education Shortchanges Unprepared Students

Blog Post

Dec. 7, 2007

Community colleges enroll nearly half of all new undergraduates each year. Yet these two-year institutions receive a much smaller proportion of public funding than their peers in the four-year sector, particularly when compared to state "flagship" universities. Recent research on the relationship between the quality of higher education and student achievement suggests that this allocation of resources is misplaced. Community colleges, it turns out, have the potential to produce the largest return on the nation’s higher education investment.

The American higher education system is built like a gigantic pyramid, with a handful of small, fabulously wealthy institutions sitting at the top and enrolling only the most qualified or wealthy students. The next level is still relatively narrow, but a little bigger, less rich, and less exclusive. And so it goes, down the ranks of money, status, and exclusivity to the wide, flat bottom of the community college sector.

This structure is an artifact of history. Most community colleges were established in the mid-20th century as an inexpensive way of getting large numbers of students through the first two years of higher education. While exclusive four-year institutions served the children of the upper class, two-year institutions disproportionately served middle- and lower-income students. These schools also received far fewer resources than private or public four-year institutions.

Few questioned the wisdom of this arrangement. The upper-echelon schools, which housed premier centers of scholarship and research, trained the best and brightest students, the nation's future innovators and leaders. Thus, it was smart to invest in these students. Or, so it seemed.

But new findings from the bottom of the pyramid suggest that these priorities are misplaced. High-quality higher education, it turns out, matters most for the students who arrive in college with the fewest resources and lowest levels of preparation. In an information-age economy where an ever-growing number of workers will require advanced skills and credentials to compete, where the last to arrive in the middle class are in danger of becoming the first to leave, the higher education resource pyramid may be exactly upside-down.

The research was conducted by the Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE), a University of Texas at Austin-based organization that administers an annual survey to students in hundreds of community colleges nationwide. The survey focuses on best educational practices, like the level of student-faculty interaction, the frequency of writing projects and class assignments, the quality of student services, and the supportive nature of the campus environment.

Recently, CCSSE commissioned a series of studies examining the link between the responses students give on the survey and their subsequent academic success.1 Not surprisingly, best practices matter—the higher the engagement level, the more likely students were to get good grades, progress through college, and graduate. These effects held even after controlling for external factors that influence student success, such as age, race, gender, the number of years since the completion of high school, the number of credits taken per semester, and pre-college test scores (given to determine if students need remedial instruction) in reading, writing, and math.

CCSSE also analyzed the effects of different dimensions of student engagement—class assignments, student-faculty interaction, etc.—on student performance, as well as the effects of engagement on different kinds of students. Chart 1 shows one such analysis.

Using regression analysis, a statistical procedure that estimates the relationship between variables, the researchers analyzed the link between survey questions related to "Class Assignments" and students' grade point averages.2 The analysis focused on over 2,000 students who enrolled in Florida community colleges as freshmen from fall 1996 through fall 2004. The grade point averages were based on the students' first three terms in college. The "Class Assignments" survey questions focus on how often students make in-class presentations, prepare two or more drafts of papers or assignments, and work on papers or projects that require integrating ideas or information from various sources.

In keeping with the overall findings, the relationship was positive—the more students were exposed to challenging, engaging class assignments, the better they did in class. That's why the lines on Chart 1 go upward from left to right; as the engagement level rises, so do grades. This was true even after controlling for the various external factors that influence student success described above.

The researchers then examined how this relationship varied among students who entered college with different levels of academic preparation, as measured by their College Pre-Test (CPT) scores in reading, writing, and math. While community college students on the whole enter college with less preparation than four-year students, there are big differences in preparationwithin every entering class, particularly in states like Florida, where community colleges enroll the majority of all college freshmen statewide.

Not surprisingly, students who entered college with higher levels of preparation earned better grades. But the degree of difference varied substantially, depending on the quality of class assignments students received.

For the most prepared students, engagement didn't seem to matter very much. This is indicated by the top line on Chart 1, which represents students who entered college with the highest CPT scores. Regardless of whether the quality of class assignments was low, high, or somewhere in between, those students on average earned about the same GPA, and always did better than their less-prepared peers.

This stands in sharp contrast with the bottom line on Chart 1, which represents students who entered with the lowest CPT scores. When these students experience low levels of student engagement, the results are disastrous: "C" averages or worse, which are strongly correlated with a risk of dropping out of school altogether. Clearly, students who enter college without adequate preparation and are then exposed to sub-standard teaching are in a world of trouble.

Unlike their most prepared peers, however, the least prepared students turned out to be highly responsive to changes in classroom practice. As the engagement scores on Chart 1 increase, the GPAs of the least prepared students increase sharply. The same pattern can be seen with the students at intermediate levels of preparation, between the top and bottom lines: the lower the initial preparation, the greater the returns of engagement for academic success.

While students of different preparation levels are separated by more than a full grade point when they experience the lowest level of engagement, that difference narrows to only .3 grade points at the highest level. The researchers also examined engagement measures other than "Class Assignments," such as "Academic Challenge" and "Student Effort," and found a similar pattern: As engagement increases, disparities between students who enter with different levels of preparation decline.

These findings suggest that the current policy of providing the most higher education resources to the most prepared college students is inefficient. The fewer social, financial, and intellectual resources students bring to college, the more they need fromcollege. Yet the present system is designed as if the opposite were true.

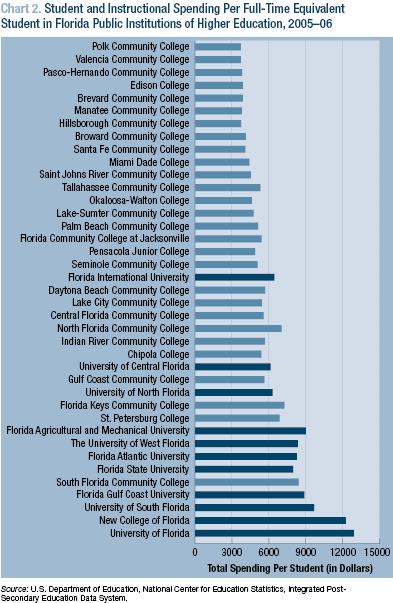

The end result of this system can be seen in Chart 2, which shows spending per full-time equivalent student on instructional and student services (not research) in Florida public higher education institutions.

The dark blue bars show four-year institutions, while the light blue bars show community colleges. The most selective institution, the University of Florida, at the bottom of the chart, spends three times as much money educating its students as the large group of community colleges at the top. These calculations don't include additional huge disparities in spending on sports, facilities, research, etc.

To be sure, high-quality higher education is about more than just money. But resources matter in higher education just like they matter everywhere else. Facilities, staffing, support services, and a host of other important things that impact education quality flow from public budget allocation decisions, which disfavor community colleges. More prestigious, selective institutions also have far more capacity to raise money independently through tuition, fundraising, and the like.

In the long run, American higher education will serve the nation better if both policymakers and institutions recognize that the students who arrive in college with the fewest resources, least preparation, and highest risk of not succeeding are also the students who stand to benefit the most from a high-quality education.

Endnotes

1. Kay M. McClenney and C. Nathan Marti, Exploring Relationships Between Student Engagement and Student Outcomes in Community Colleges: Report on Validation Research (Austin, TX: The Community College Survey of Student Engagement, The University of Texas at Austin, December 2006).

2. This analysis was conducted by a team at the National Centerfor Higher Education Management Systems led by Peter Ewell. They describe the analytic process as follows:

"Because conditional effects have appeared intermittently in previous studies examining the relationship between CCSSE … responses and actual outcomes, a particular effort was made in this study to look for such effects in two areas: student academic ability and minority status. At issue was whether engagement matters more or less for students who enter with differing levels of academic ability or for minority students vs. white students. To investigate these questions, two sets of interaction variables were computed for all CCSSE clusters by multiplying each cluster by total CPT score and by minority status. Each of these interaction variables was then entered into a regression on overall GPA together with all previous controls and the CCSSE cluster to which the interaction variable corresponded… No significant results were uncovered for the minority interaction variables in either sample, but a number of independent significant interaction effects were revealed for entering ability in both of them. Consistent with previous studies, these showed that higher levels of engagement boosted GPA for students with low CPT scores, but not for students with high CPT scores."

This work by Education Sector is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Education Sector encourages the free use, reproduction, and distribution of our ideas, perspectives, and analysis. Our Creative Commons licensing allows for the noncommercial use of all Education Sector authored or commissioned materials featured on this site. We require attribution for all use. Link to and credit Education Sector as the original publisher of the work and, if applicable, also credit a particular author.