Cosmetology Without Accountability: Failures of a Beauty School Accreditor

Brief

Dennis MacDonald via Shutterstock/Natalya Brill/New America

Oct. 16, 2025

A year ago, a small, for-profit beauty school in Texas was informed it was losing its accreditation.

Accreditation is supposed to signify that a college has met certain quality standards—that a school has proven to an outside entity, the accreditor, that it has the staff, finances, facilities, and academic track record to educate students. Accredited colleges are the only institutions that can accept federal financial aid, such as Pell Grants and student loans, which taxpayers fund.

This arrangement is meant to ensure that student and taxpayer money doesn’t reach predatory, fraudulent, or underperforming institutions. Accreditation, therefore, is a consumer safeguard, at its core. And many students choose a school assuming an accreditor has already vetted it. That’s why federal regulations require colleges to accurately disclose their accreditation status, as well as actions accreditors take against them.

This Texas college, however, did not divulge, on either its website or public course catalogue, that its accreditor had moved to withdraw accreditation in October 2024. Pearlands Innovative School of Beauty staff also does not disclose this fact.

We posed as prospective students, as part of a secret-shopping effort to test whether colleges sanctioned by their accreditor would accurately describe their accreditation status. We spoke to two Pearlands staff members by phone in spring 2025. Neither official shared the school’s problems when asked about its accreditation. They also provided different answers about the entity accrediting the institution. One said the state of Texas, the other the U.S. Department of Education.

Neither response is correct.

Pearlands’s accreditor is the National Accrediting Commission of Career Arts and Sciences, or NACCAS, an agency specializing in beauty schools. NACCAS has existed for decades. But its practices, revealed in this analysis, call into question its efficacy as an accreditor. It has routinely failed to enforce federal regulations and its own rules requiring colleges to accurately publicize their accreditation standing. More than a dozen institutions that NACCAS placed on probation in the past year or so failed to meet that basic transparency mandate, our research found.

NACCAS’s oversight methods undermine the premise of accreditation as a consumer protection. It permits colleges with ongoing compliance issues to continue enrolling students and drawing down federal financial aid, even when NACCAS has repeatedly punished them or moved to revoke their accreditation entirely.

The problem lies in how NACCAS evaluates rule violations. Instead of assessing a college’s full record, NACCAS treats each infraction as a stand-alone matter. This piecemeal approach obscures the severity of persistent problems at its schools. For example, NACCAS issued a “show-cause” order to a school called Arizona Academy of Beauty in October 2024, according to a public database. A show-cause order in accreditation is an indication of a serious rules infraction that could lead to loss of accreditation. Arizona Academy had failed to submit audited financial statements, which NACCAS relies on to determine whether a college has sufficient funding to deliver a quality education. Two months after NACCAS issued the order, it sought to revoke Arizona Academy’s accreditation. However, in February, while the school appealed that decision, NACCAS sent another show-cause order for another violation—the school again hadn’t provided its financial statements. But NACCAS’s choice to even send another show-cause order was nonsensical, as it had already started to pull the school’s accreditation over the same issue.

By addressing one transgression at a time, NACCAS enables institutions to maintain their accreditation even as problems proliferate. For instance, a college on sanction might have a year to correct a problem. But if a new issue arises during that period—and the college resolves the original one on time—it essentially gets an extension, even for the same issue. Schools can cycle through violations this way for years. They are technically sanctioned, but still open, still enrolling students, and drawing federal aid despite ongoing rule violations. This approach is at odds with expectations in federal regulation and with how other accrediting agencies address colleges that aren’t meeting the rules.

At their most egregious, NACCAS institutions can lose their accreditation more than once for multiple consecutive violations yet remain up and running for months while they appeal. Students who attend these colleges almost certainly lack the policy literacy to untangle NACCAS’s web of rules and penalties, especially when those institutions aren’t publicly sharing their problems.

Congress and the U.S. Department of Education have the power to correct this problem. Lawmakers should more clearly outline an accreditor’s obligations when colleges violate their rules. The Education Department, the agency that screens and approves which accreditors can unlock financial aid, should investigate whether NACCAS demonstrates the capacity and willingness to hold institutions accountable. If the department finds that it does not, it could strip NACCAS’s authority to oversee colleges. The Education Department could also strengthen its rules guiding the sanctions accreditors use and the time institutions have when they don’t meet standards.

How Accreditation Is Supposed to Work

The federal government invests vast amounts of taxpayer money into financial aid for students’ postsecondary education, distributing more than $120 billion annually in grants, loans, and work-study funds. To help safeguard this federal largesse from underachieving colleges—and outright scammers—the government taps outside organizations, called accreditors, to appraise institutions.

Accreditors judge whether colleges meet education quality standards, typically by visiting campuses and reviewing troves of materials the schools provide, including financial audits and a self-assessment of how they operate. Accreditors dig into factors like faculty qualifications, curriculum, and financial stability. By law, accreditors function separately from the Education Department, which cannot interfere with how they craft their standards or whether they punish colleges in their purview. However, the Education Department does decide which accreditors meet federal standards to serve as gatekeepers to financial aid.

Today, the department recognizes over 60 accreditors. Nearly 40 of those agencies accredit entire colleges, which allows institutions to participate in federal aid programs. The other recognized accreditors only approve specific degree programs, which makes them eligible for other federal funds, such as U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grants. Some accreditors approve both institutions and programs.

Every five years, the Education Department reviews each accreditor in a process that typically spans two or so years. This is to ensure that department-recognized accreditors are continuing to meet specific federal requirements. Accreditors must submit a report to the department detailing how they apply their standards across different areas. The department also shadows an accreditor during campus site visits and observes one of its meetings where policies are set and sanctions considered. A federal advisory board, the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, or NACIQI, also recommends whether to renew an accreditor, but an Education Department official makes the final call.

The Education Department has recognized NACCAS since 1970. It was known as the Cosmetology Accrediting Commission, created from a merger of two other accreditors, until 1981. NACCAS accredits more than 740 schools receiving federal money, which is roughly one out of every seven institutions eligible for federal financial aid, according to Education Department data. Those colleges took in more than $1 billion in federal aid and enrolled 109,000 students in the 2022–23 academic year.

These institutions need strict oversight because research shows that students at beauty schools are far less likely to graduate or find good jobs than those at nearly any other type of federally supported college. Nationally, beauty school students are much more likely than other students to earn less than a high-school graduate after finishing their credential—by $5,000 to $14,000 on average, according to a New America report published in March. Four years after graduating, the typical cosmetology student makes only about $20,000 and those who borrowed for their education hold $10,000 to $14,000 in federal loans. Unemployment among for-profit cosmetology school alumni tops 10 percent, more than three times the national unemployment rate, according to the New America report.

In interviews and focus groups, cosmetology students and graduates told us that their programs were often second-rate, and that they contended with problems ranging from outdated curricula to high instructor turnover. This environment raises questions about whether programs like these are worthy of federal subsidies if their graduates have difficulty landing work and instead could be burdened with crushing student debts. Cosmetology programs often attract more women and students of color, too, meaning heavy debts, for instance, disproportionately fall to them. Women and students of color are more likely to borrow and struggle to repay debt in many industries, too, since they earn less than their white male counterparts. NACCAS’s role as a sector watchdog is critical, but it’s one that it hasn’t fulfilled. It hasn’t protected students.

How NACCAS Approaches Rule Violations Versus Other Accreditors

NACCAS Executive Director Darrin Wallace defended its practices in a letter to New America’s researchers. The accreditor treats every potential rule violation as a “unique process” to ensure that colleges receive due process, he wrote, in response to a question about why the agency would levy new penalties when a school is already on the same sanction for a different problem. “Among other things, this approach explains the existence of concurrent processes that, absent that context, might appear incongruous,” Wallace wrote.

NACCAS maintains a complex sanction system. It might place colleges that run afoul of its policies on a range of “probation or equivalent" processes, which can include anything from actual probation to monitoring according to its 172-page NACCAS handbook. It also can place a college on a formal “probation” status, and while an institution can only be on one probation at a time, that school can accumulate additional violations that are “probation or equivalent.” Institutions can face overlapping punishments at one time, but NACCAS does not rank the severity of infractions, meaning all of them could lead to accreditation loss. In this way, NACCAS lacks clear procedures for addressing concurrent violations. Table 1 outlines the NACCAS sanction system.

Other accreditors employ more comprehensible methods. The Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission, for example, uses progressive sanctions to indicate the seriousness of noncompliance—notice of concern, warning, probation, and show cause—and each level comes with different oversight and restrictions. These sanctions are not issued concurrently.

Similarly, the Middle States Commission on Higher Education uses progressive sanctions. Each action explains what problems have been fixed, what issues remain, and what new violations have been found, rather than creating separate sanctions with different timelines or in a way that extends deadlines.

Accreditors that issue one sanction and adhere to one timeline provide clarity to policymakers, the public, and most importantly, students. Using one sanction instead of multiple concurrent ones also provides the opportunity to escalate the severity of action and the resulting limitations on an institution when it is out of compliance.

On disclosures, NACCAS’s policies resemble those of other accreditors. But some accreditors go further. The Higher Learning Commission, or HLC, for instance, asks its colleges to send it the language of how they will disclose accreditation status, for approval. HLC also has created digital icons that colleges place on their websites that advertise their accreditation status. These icons link to HLC’s website, which explains why a college may have been sanctioned and what that means for students.

Wallace did not respond to our questions about whether NACCAS checks if colleges accurately disclose their accreditation status and the sanctions against them. He did not say if there are consequences for schools that fail to accurately disclose their status. He only noted that as a private entity, NACCAS has no power to compel colleges to comply with its rules once they no longer have accreditation.

No Disclosures, Many Problems

Many of NACCAS’s colleges are violating both federal requirements that mandate that students receive accurate information about accreditation status and NACCAS’s rules about how colleges must publicize their standing.

If a college publishes its accreditation status, federal regulation mandates that its accreditor ensure that information is correct. Under another regulation, accreditors must verify that colleges under their watch notify current and prospective students when they are placed on probation or issued a similar sanction.

NACCAS’s policies likewise demand that colleges correctly advertise their accreditation status, including any penalties against them, anywhere institutions display this status: on their websites and social media, for example, or in their course catalogs. NACCAS reiterates this obligation in the formal letters it sends when sanctioning schools.

As part of our analysis, we reviewed the websites and virtual course catalogues of more than two dozen NACCAS-accredited beauty schools that the accreditor put on probation between April 2024 and April 2025. We found that schools often failed to note on either their websites or course catalogues that they had been placed on probation. Even when institutions accurately reported their accreditation status in one place, they often omitted it elsewhere. For instance, they might disclose their probation status in a course catalogue but not on their website, leaving both current and prospective students with incomplete or misleading information.

One example of this is La’ James International College, a for-profit beauty chain based in Iowa with a history of legal and government scrutiny. Several lawsuits, including a couple from the state attorney general, accused it of misleading students about financial aid and the quality of its programs. NACCAS has moved all of the school’s campuses to probation. However, the only acknowledgement on the school’s website of this fact is buried in a school catalogue footnote. Its website states that La’ James is NACCAS-accredited but does not mention the probation.

La’ James was among several schools, including Pearlands in Texas and the Arizona Academy of Beauty, which failed to disclose NACCAS’s sanctions when we contacted them as part of our secret-shopping research. Two to three New America researchers participated in secret shopping over several months. While one of us posed as a student, another would take notes on their conversations, ensuring that none were recorded without permission.

Carey White, owner of the Arizona Academy of Beauty, told one of us who was posing as a prospective student, that the school was accredited—in May, the same month NACCAS had started withdrawing its accreditation. This “gives you the opportunity to qualify for grants and loans,” White said, failing to share that the school was on probation, and that it was on the verge of losing accreditation. That information is also missing from the school’s website, which states that it is accredited. Arizona Academy formally lost accreditation in July. It’s unclear if, or how, it communicated these developments to its students.

In another example, in February, NACCAS started revoking accreditation for Albany Beauty Academy, a Georgia-based cosmetology school, in February. Albany apparently maintainstwo different websites. Neither of the websites nor the course catalog allude to the probation or withdrawal, which seems to be pending appeal.

Other NACCAS colleges that we reviewed similarly lost accreditation entirely but continued to claim online that they had NACCAS’s endorsement. For example, BJ’s Beauty and Barber College in Tacoma, Washington, was told in May that NACCAS would rescind its accreditation, according to public records, but as of late August, its website advertised NACCAS approval.

NACCAS and other regulators must confront this deception. Accurate communication of accreditation status is not an arbitrary technicality. Accreditation signals that a college meets basic benchmarks and that students can reasonably expect their education investment to lead to career and economic mobility. Colleges that conceal or misrepresent their accreditation status are cheating students, especially those who would have enrolled elsewhere had they known about an institution’s problems.

At cosmetology schools, students might think that they’re working with an accredited institution that will train them to, for instance, obtain licensure and establish a beauty career. Under NACCAS’s laissez-faire oversight, beauty schools can essentially claim that their programs have been vetted, even if they might not meet accreditation standards.

Students who don’t receive a quality education might not reach licensure, and they won’t be able to work in their chosen profession. Meanwhile, students are eligible for a limited amount of federal grants and loans, meaning they won’t necessarily be able to rely on financial aid if they wanted another credential. Instead, they could be saddled with ruinous amounts of debt. About 90 percent of graduates at for-profit conglomerate beauty schools didn’t earn more than they would have with just a high school diploma, according to the research.

Students’ credits from floundering schools also often cannot transfer to another institution, and so unwittingly enrolling at a sanctioned or unaccredited school can mean wasted money and stalled careers, a loss of opportunity for students who can least afford it.

(Not) the Sum of Its Parts

When a college doesn’t meet accreditor standards and can’t come into compliance with them in a timely way, that institution shouldn’t be able to cash in on students’ financial aid. Federal regulations support this concept. These rules require accreditors to prove they can identify and track problems with the schools they green-light. If an accreditor discovers issues, then an institution gets a set period, tied to the length of its programs, to resolve them or risk losing accreditation.

NACCAS’s tactics, however, essentially allow their institutions to be out of compliance indefinitely. Because of its methods of evaluating each potential rule violation as a separate problem, NACCAS colleges can hold onto their accreditation, continue enrolling students, and collect federal aid for years, even while failing to meet multiple benchmarks.

Pearlands, the Texas school, faced financial turbulence before NACCAS started to repeal its accreditation in October 2024. NACCAS twice sanctioned it in 2023, with a penalty known as monitoring, and gave it until August 2024 to fix the financial issues or possibly lose accreditation. NACCAS treated the monitoring as equivalent to probation. Under NACCAS rules, a college can have more than one action against it that is equivalent to probation but can carry only one probation. In June 2024, NACCAS formally put Pearlands on probation for the still-unresolved financial problems. Four months later, NACCAS moved to rescind Pearlands' accreditation. But according to the NACCAS website, as of fall 2025, inexplicably, it had renewed Pearlands’ accreditation, with no public explanation as to why. An Education Department database does not show if or when Pearlands appealed the accreditation withdrawal.

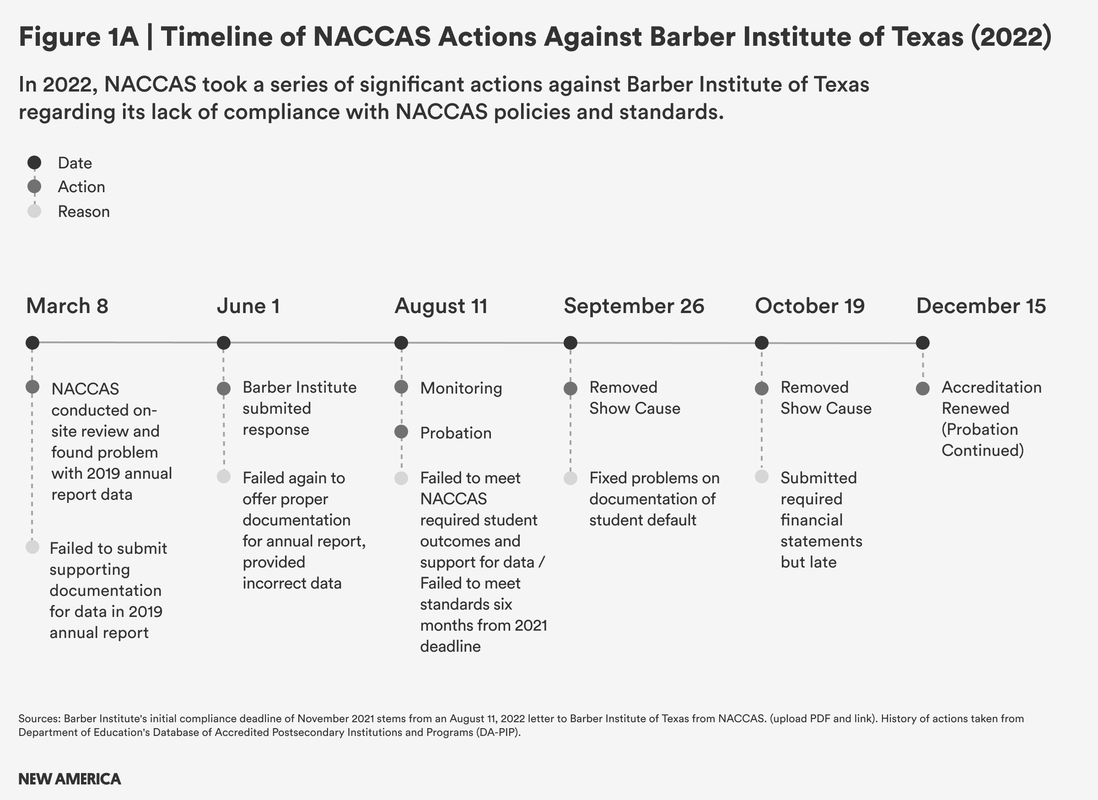

Another example of NACCAS’s problematic approach is its handling of the Barber Institute of Texas, which lost accreditation in December 2024. NACCAS demands that college programs graduate at least 50 percent of students, that 70 percent pass licensure tests, and that at least 60 percent find jobs after leaving school.

But NACCAS, after a March 2021 visit to the school’s campus, found it couldn’t verify the veracity of its 2019 student achievement data. NACCAS gave the school additional time to pony up that data. It didn’t. As a result, NACCAS began monitoring the school, setting a November 2021 cutoff to address the problem. Except NACCAS informed the school of this 2021 deadline in a letter in August 2022—almost a year after the institution was supposed to have rectified its data.

That same day it issued a deadline, NACCAS formally placed the Barber Institute on probation for coming within six months of the deadline that was already in the past. But it created no clear new timetable for compliance, effectively leaving the school without one. NACCAS calculated that the school should have had no more than a year to correct its problems before it lost accreditation in August 2023. But the school’s problems continued to pile up through the end of 2024.

In response to questions from us about setting compliance deadlines that have already passed, Wallace, the NACCAS executive director, wrote a letter in which he explained that it previously assigned a school placed on low-outcomes monitoring the same deadline it would have received if it self-reported noncompliant outcome rates. However, the accreditor no longer uses this methodology, after concluding that “prospective deadlines provide clarity, consistency, and fairness” with “a clear window of time to demonstrate compliance,” Wallace wrote.

Source: Graphic by Natalya Brill

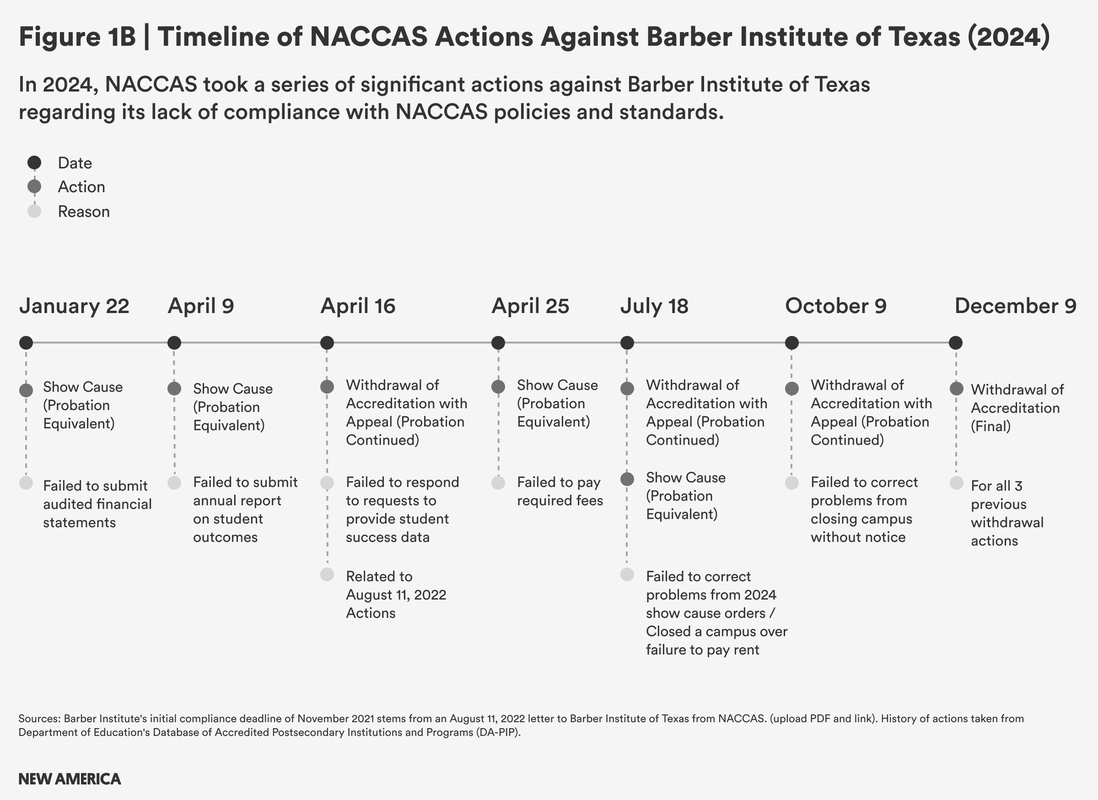

Source: Graphic by Natalya Brill

Between late 2022 and 2024, NACCAS issued multiple show-cause orders to the Barber Institute over missing financial statements, unpaid fees, and failure to report accurate performance data. It moved to withdraw accreditation three separate times in 2024, but on each occasion, the process dragged on as the school appealed. During this period, one of the school’s locations closed after the landlord changed the locks over unpaid rent, but the Barber Institute attempted to keep students enrolled by shifting them to another site.

In December 2024, NACCAS officially withdrew the institution’s accreditation. Over the course of the years NACCAS was investigating the school, Barber Institute kept enrolling students, many of whom needed financial aid to pay for a school with an extended list of problems. Students likely never learned about NACCAS’s sanctions because the school never revealed them on its website, according to an archived version.

The Barber Institute’s students don’t seem to be faring well, either. About two-thirds of Barber Institute students who took on loans from 2020 onwards were more than 90 days delinquent in paying them, according to New America’s analysis of Education Department data, which was published in July.

NACCAS has justified its procedures by pointing to the need to provide schools with due process. Unless accreditors reconcile the gap between procedural fairness and timely accountability, however, institutions like Barber Institute will continue to test the limits of federal rules requiring entities like NACCAS to set a firm deadline for loss of accreditation for failing schools. NACCAS’s approach is at odds with the spirit, if not the letter, of the rules that expect noncompliance to be limited to a set amount of time.

Four Recommendations

NACCAS’s practices prove that, in the American higher ed accountability system, oversight without enforcement is no oversight at all and comes at the expense of student well-being and public dollars. If NACCAS cannot meet the responsibilities entrusted to it, policymakers must act. To that end, we recommend that:

NACCAS Revise its Policies.

The accreditor is routinely failing to hold schools under its stewardship accountable. NACCAS should make explicit that all institutions must accurately advertise and inform students of their accreditation status, including when schools are subject to probation, show-cause orders, or loss of accreditation but subject to appeal. NACCAS should follow up with schools to ensure they’re carrying out this directive. NACCAS should mandate that schools share exactly how they are informing current and prospective students about accreditation status.

NACCAS should also revise its approach to concurrent sanctions. A school is either in compliance with all NACCAS policies and standards, or it’s not. A school shouldn’t get multiple sanctions on the same day for nearly identical issues, like missing required paperwork or financial troubles. There should be one sanction with a single deadline to prove the school can meet both administrative and financial standards. Otherwise, students are left enrolling at a school that clearly isn’t following the rules. When a school racks up multiple sanctions, NACCAS should escalate its response, imposing absolute limits, like enrollment caps or additional monitoring and reporting, until the school proves itself.

Finally, NACCAS should cut down on how long schools can remain on appeal after losing accreditation. An institution should not continue operating long after accreditation was withdrawn, enrolling students and taking their financial aid dollars.

The Education Department Investigate NACCAS.

The Education Department has the power to determine whether an accreditor is a reliable gatekeeper to federal aid. NACCAS’s record raises serious doubts about this policing power. This example shows that lack of strong enforcement can allow chronically underperforming colleges to continue enrolling students and drawing taxpayer money. The Education Department must formally review NACCAS’s policies, judging not only whether it meets federal standards on paper, but also whether in practice it is helping safeguard students from institutions with persistently poor outcomes. If NACCAS cannot demonstrate the capacity and willingness to hold its schools accountable, the Education Department should limit its ability to accredit new schools until it can prove it’s enforcing its standards or remove its recognition altogether. When the Education Department is evaluating other accreditors, it should make sure that they too are enforcing disclosure policies.

The Department Draft More Precise Accreditation Rules.

Federal regulations already require accreditors to set enforceable timelines for institutions to correct violations or otherwise lose accreditation. But NACCAS’s methods expose the gaps in how those rules are written. The Education Department must tighten its regulations to eliminate ambiguity. That means requiring accreditors to consider a college’s complete record of violations together, not one at a time, and to set hard deadlines for resolving problems.

Congress Pass Legislation to Protect Students.

Because students must not be exposed when accreditors fail, federal policymakers must explicitly outline accreditors’ obligations when colleges repeatedly infringe on their standards. The legislation should institute stronger protections for students whose colleges are under accreditor scrutiny, as well as punishments for accreditors that don’t carry out their own rules. Without a statutory backstop, accreditors like NACCAS can continue to disregard systematic problems at their institutions. Clear, enforceable legislation would help restore integrity to the accreditation system.

Accreditation is a system built to protect students and taxpayers. NACCAS has turned it into a shield for failing schools. Its leniency results in public money propping up institutions that the government should have cut off long ago.

Updated on October 21, 2025: This brief has been updated to correct the accreditation status of Pearlands Innovative School of Beauty, which was not current in the U.S. Department of Education's Database of Accredited Postsecondary Institutions and Programs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Gates Foundation for its generous support of this work. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Gates Foundation.