Transforming Lives with Child Care and Community Engagement: A Two-Generation Approach

A New Head Start Center in Ohio Offers a Model to Benefit Children and Parents

Brief

Lina Kivaka/Pexels

Dec. 17, 2024

For families in East Dayton, Ohio, the lack of high-quality child care keeps parents out of work. But a history of distrust and poverty means that the community engagement and input into the process of constructing and opening a new Head Start center will be crucial for families to utilize it. In addition to providing high-quality child care and promoting kindergarten readiness, the new Head Start center will have wrap-around community services, including health care and adult education opportunities, which are part of a two-generation approach to break the cycles of poverty and political disengagement that have persisted in East Dayton, as compared to surrounding neighborhoods, where quality child care is more prevalent and poverty less rampant. Key takeaways include:

- The lack of high-quality, accessible child care keeps many families out of the workforce. For families at or below the poverty line, the second income they are forced to forgo without child care options could make a significant difference for family economic stability and well-being. If we want to create pathways out of poverty, establishing strong, affordable, and high-quality community-based child care options are crucial.

- Creating a new child care center in the midst of a lower-income area that has traditionally not had access to or relied on child care outside of the home requires community input and democratic, inclusive forms of engagement. This type of engagement is most effective with the trusted community connections that come from repeated interactions, opportunities for feedback and collaboration, and incorporating such feedback in the final results.

- The two-generation approach to combating poverty begins with child care, but also requires additional wrap-around services, such as access to health care, social services, and opportunities for connection. The advantage of a new Head Start facility that includes community services with accessible transportation options can provide that.

- Access to quality early childhood education will allow more children, especially those from impoverished and under-resourced communities, to be more prepared for kindergarten. Kindergarten readiness is a crucial factor in long-term positive educational outcomes and has the potential to help disrupt generational cycles of poverty.

Where Brandon and Edie live, they don’t have access to child care.

For Edie, it’s a matter of trust. She works as a shift supervisor at Panera Bread, “one of the best jobs” she’s ever had, she tells me. She is the sole breadwinner for their family. She and her longtime partner Brandon have three boys at home, ages 14, 16, and three. Her kids have been in child care before. Edie recalls a time when her middle son was in child care: She and Brandon would walk him to child care before continuing to walk to their jobs—which was then cleaning at a local hotel. This walk was five miles roundtrip when neither of them had a car.

But the woman who ran the child care center was someone Edie didn’t fully feel comfortable leaving her child with at the time, and she didn’t have access to any other child care options in the area, given the scarcity of high-quality options available.

“I just got a vibe from the lady [working there] that she was lazy,” Edie said. “I came outside and my son was crying and she was yelling, ‘Be quiet.’ She acted like I didn’t hear that. When I went back in after I heard her yelling, she said he was just crying because he dropped his pacifier, but he doesn’t take a pacifier.”

“I’m scared more than anything,” she says. The fear runs through a lot of their daily living activities—she describes the neighborhood they live in as a place where, by their description, drug-addled “zombies” walk around the street. On the day that I visit, they reference the one that is lurking outside their home, and, as we drive, they point out another man passed out in the street. There is also the need for transportation. For years they didn’t have a car, until a friend of a friend donated one, but even then there are few places to go. They don’t trust the neighborhood parks, they don’t feel comfortable walking around the street, and their older two boys are in an online homeschool through Dayton Public Schools—so they, too, rarely leave.

Brandon currently doesn’t have paid work. He has struggled to find a position he could keep for a stretch of time. He worked part-time at Panera with Edie until August, because they struggled to have child care coverage with both parents needing to work in set shifts. So Brandon, who made less money of the two, quit to become the primary child care provider for their three boys, monitoring their home school and trying to help the youngest learn his ABCs. For Brandon, being a stay-at-home dad is really important to him, both to strengthen his relationship with his own kids but also because his father was largely absent. He sees his work as a role model for them, and as a testament to the type of family life he and Edie are building together—one that is stable and loving.

Edie says she prefers this arrangement where Brandon stays home because there is no one she trusts to watch her children while she works.

But they both know that a second income would make a significant difference. It would repair the old car they have, purchase clothes for their growing kids, allow them to access quality medical care for lingering injuries and dental work, and even buy better shoes and clothes for themselves. As Edie explains it, “We go without for just about everything.”

A New Head Start, and a Child Care Opportunity

For Brandon and Edie, a change may be coming. Nearby, a half mile away, a new Head Start building is opening to serve the East Dayton community.

They’ve seen the new building go up—the construction effort stands out in a neighborhood of mostly vinyl-sided homes. It’s a $13 million dollar facility, with a community space, health clinic, and the type of investment in high-quality child care that has the ability to be transformative for communities.

The official name for the building is the Miami Valley Child Development Centers in Ohio (MVCDC) Lincoln Hill Head Start. The building will have 14 classrooms—five infant toddler (Early Head Start) classrooms and nine preschool (Head Start) classrooms. Berta Velilla, the CEO of MVCDC, estimates they will be able to serve 250 students, with both full-day and part-day options available. A ribbon cutting is planned for March 2025, a soft opening scheduled in April, and the center will be fully operational in July 2025. According to current data from the Center for American Progress, the area of East Dayton is both high poverty and lacks access to quality child care.

In a program like Head Start, providers often receive better pay and benefits than in the regular child care marketplace. Head Start teachers are expected to have, at a minimum, an associate’s degree in early childhood education, and Early Head Start teachers will have a Child Development Associate’s degree. Starting pay is $17 an hour for an assistant teacher, with lead teachers being able to earn $28–$29 an hour, depending on their experience. This is far higher than Ohio’s minimum wage, which is going up to $10.70 per hour in January 2025, and also higher than the average child care worker pay in Ohio, which is $12.89 per hour. By being connected to Head Start, the teachers are eligible for benefits like medical insurance, retirement, tuition reimbursement, and professional development opportunities.

A History of Exploitation and a Cycle of Poverty

East Dayton has one of the lowest rates in accessing early child education, as measured by Preschool Promise, the local nonprofit that works to increase access and quality in early childhood care. “In the 2022–2023 period approximately twice as high a percentage of four-year-olds in West Dayton than in East Dayton were enrolled in Preschool Promise, (43 percent vs. 22 percent) and attending a Preschool Promise affiliated site,” said Richard Stock, the director of the Business Research Group at the University of Dayton who estimates preschool enrollment as part of his evaluation work for Preschool Promise, which is affiliated with most child care sites in Dayton.

“You can’t break the cycle of poverty and political disengagement without kids getting a good education,” says Jan Lepore-Jentleson, executive director of the East End Neighborhood Development Corporation. She explains that historically, East Dayton has had fewer child care options than nearby neighborhoods in North and West Dayton. Some of this is because of the deep Appalachian history in the area, which had a “cultural carry-over that kids should stay home with mom until they are five, and when you turn five you are ‘ready’ for kindergarten, as opposed to other parts of town.”

Elizabeth Gish, a senior program officer for democracy and community at the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, has long studied the Appalachian history of East Dayton in the post-World War II migration and the way the longstanding mistreatment and exploitation of the Appalachian community has led to this cycle of poverty and addiction.

“Appalachians have a long history of being fiercely independent and mistrusting of outsiders. This is due in part to the geography of the mountains: Families and communities tended to be more isolated and disconnected because of terrain. But it also comes from a long history of exploitation,” Gish said.

“There is this great song by Tyler Childers, a popular Appalachian singer, titled ‘Coal.’ He says: ‘And in my darkest hour, I cry out to the Lord. He says, ‘Keep on minin,’ boy. ‘Cause that’s why you were born.’”

“There is this recurring theme in the history of the Appalachian people that somehow this is what Appalachian people are for: Our people, our land, our homes, our children, and our stories are just there for the taking. ‘That’s why you were born,’” Gish said. “They have long been exploited for their land, labor, or for how many pills they can buy from Purdue Pharma. So you can see why there might be a trust issue with child care.”

East Dayton has been one of the hardest hit areas of the opioid epidemic. “Of the 566 deaths in Montgomery County [Dayton] in 2017, half of them were in East Dayton,” says Lepore-Jentleson. She says 2017 was the “worst year in history for this community,” though things have gotten better since then. She credits the widespread availability of Narcan and rehabilitation with those improvements, but the problems of opioid addiction still persist, as does the lack of trust in institutions, politics, and outsiders.

The lack of trust in child care by perceived outsiders has created low demand, and the lack of demand means high-quality child care won’t have a market to succeed. This lack of quality child care in East Dayton has led to even further marginalization of the families that live there from labor systems, educational systems, electoral systems, and pathways to affordable, stable housing. It keeps parents like Brandon from working and making a second income that would help lift his family out of poverty. A public program like Head Start allows providers who want to go into early care and education to do so at a more competitive pay rate.

For Lepore-Jentleson, the lack of high-quality child care means that more kids head to kindergarten unprepared for their education, as evidence shows that quality early education provides improved readiness for kindergarten.

“‘Kindergarten readiness’ is a whole lot more than just turning five,” said Lepore-Jentleson. “Right now so many of the kids who come to Ruskin [the local elementary school] can be two to three years behind cognitively and socially.” She cites examples of kids who prefer to cower under their desks or have a lot of tears transitioning to school. “We see this with kids who have not had high-quality preschool. If they fall behind grade level with their peers, it can be hard to catch up,” she says.

Gish adds that “high-quality child care is an essential piece of the puzzle if we want families to have the bandwidth to take part in their communities and be a part of a more broadly inclusive democracy beyond just keeping their heads above water.”

From Bowling Alley to New Multi-Million Dollar Facility

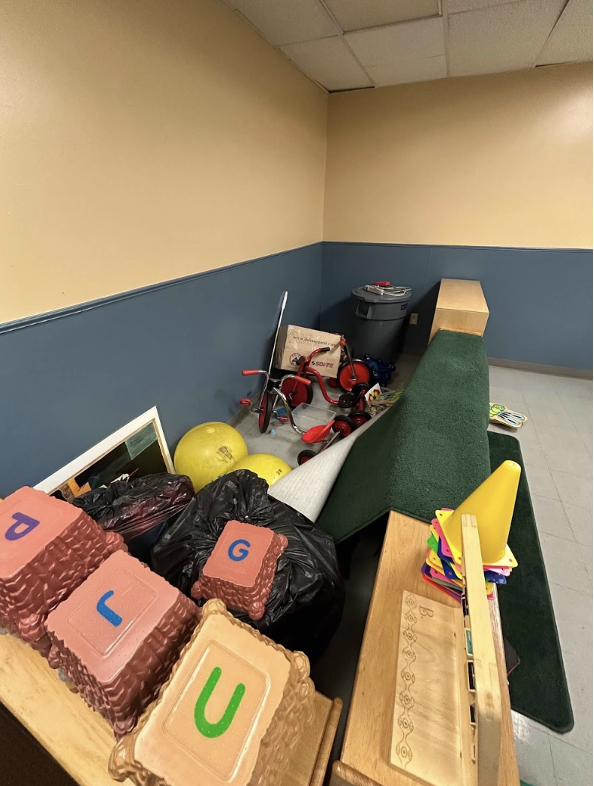

Currently, there is only a single licensed child care facility in East Dayton, as defined by the 310 zip code. It’s located in a former bowling alley, with several classrooms dedicated to serving children in the Head Start program. The landlord is a church, whom Berta Velilla, the CEO of MVCDC, describes as supportive. But traditional child care centers are not designed to fit into bowling alleys, nor is the church able to pay for sufficient upkeep. One side of the main room is cordoned off because the floors are sinking in, with shelves of toys propped up as barricades so that kids stay away from that area. Outside, the bottoms of the metal doors are rusted through. Above the entrance is a framework for an awning, but only fragments of cloth remain. Since there is no adjacent playspace, the kids have to walk down the block and cross a quiet street to go to a playground, which lacks modern playground equipment. When we approach this playground, the dog next door barks and snarls. In a pile of trash on the ground, a hypodermic needle sticks out.

The current playspace in the single licensed child care option in East Dayton.

Source: Rebecca Gale/New America

There is only one licensed child care center in East Dayton, and part of the floor is sinking in. The center has cornered off the space so that children do not play there.

Source: Rebecca Gale/New America

The back entrance to the only licensed child care center in East Dayton, in which the door is rusted and rotted through.

Source: Rebecca Gale/New America

Community advocates and organizers and those who work in early education knew that East Dayton needed to have more high-quality child care facilities available, but the market itself would not solve the problem. The goal, explained Velilla, was to create a facility that would both increase the number of high-quality early child care spots and do so in a way that allowed for wrap-around services such as health care, early intervention specialists, and support with housing, bills, and transportation.

In 2013, a five-acre property where the Lincoln Hill Elementary School had been located was put up for sale by Dayton Public Schools. As Lepore-Jentleson explained, the building was built in the ’30s and nearing 100 years old with declining enrollment; the neighborhood didn’t have enough students to support two schools, so the decision was made to tear Lincoln Hill down rather than repair or rehabilitate it. East End Community Services made a bid for the property, and in 2014 purchased it for $35,000. Child care hadn’t been the initial goal though. Originally the East End Community Services group viewed this as a potential option to build affordable housing. But the topography of the area made it challenging to build on, and they were not able to come up with a plan that would provide a sufficient number of housing units to qualify for housing subsidies.

So what should it be instead? The question was put out to the community—with the understanding that any social services option would be best utilized if the community could weigh in directly on how they space should be used. “We leafletted the neighborhood,” explained Lepore-Jentleson. They had people that could go door-to-door around the perimeter of the block and invite people to the meeting, which was held at a local community center down the street from the East End Neighborhood Development Corporation.

“We did a tag team,” Lepore-Jentleson said, referring to working with Mary Burns, who was then the director of MVCDC. “We had a really good turn out and said: ‘Here is what we are thinking, community. Are you in favor of this? What are your concerns?’”

This sort of community building approach was successful because East End Community Services has a long track record of actually listening to the community, trusting neighbors, and keeping promises, explains Gish. “You can’t just show up and leaflet out of the blue and say ‘Oh we’re here to do a survey and have a listening session.’ People do not have time for another pro forma community engagement effort. A key reason I see this as having worked is because the folks leading the efforts were willing to be patient, were committed to East End over decades, and really honored and elevated the knowledge and expertise of the people in the neighborhood. They know their lives and situations, and Lepore-Jentleson and her team are there to facilitate pathways and connections to help bring that into being.”

“One of the most difficult things is to get people to come to things,” said Destiny Brown, in a conversation about the challenges connecting to the community. Brown is a community organizer at Advocates for Basic Legal Equality in Dayton and a Kettering Foundation Dayton Democracy Fellow. “People do not have the capacity or the support they need to join in things—they have to make the capacity to deal with one more thing. They will only do it if they think they might actually get change. A lot of times, that doesn’t seem very possible.”

The new Head Start building is designed so that it does not block the neighbors’ view of downtown Dayton.

Source: Photo courtesy of Berta Velilla, used with permission.

The outside of the new Head Start in East Dayton, before its completion expected this spring.

Source: Photo courtesy of Berta Velilla, used with permission.

One of the points of feedback they received was that the community enjoyed seeing downtown without the building blocking their view. So the original plan was to focus the architectural design on the lower half, though a wetlands area changed that plan so the new design had the building below street grade—maintaining the view and giving the community validation that their concerns had been heard. “But everyone thought it was a good use of the space,” Lepore-Jentleson said.

“Change moves at the pace of trust,” said Gish. “I see one of the key factors in this work being able to happen in the East End, as well as the great work with child care and education that is happening with Omega CDC in Northwest Dayton [a nonprofit dedicated to breaking the cycle of poverty], comes from the patience with building relationships that are honest, trusting, and equitable. Where we don’t just give lip service to trusting and honoring the lived experience of impacted people, but we actually do that, realizing that the people who experience disinvestment everyday know what they need. This is not the most ‘efficient’ way to work in the short term, but long term this is what produces results that meet the needs of people in ways that are democratic, sustainable, and scalable.”

A Two-Generation Solution for the Community Begins with Early Care

From its inception, Jan Lepore-Jentleson has understood that for the child care center to thrive, it will need the trust and buy-in of the families in the community, parents like Brandon and Edie who have long been distrustful of the systems that claim to help them. Neither of them have ever voted, nor found a child care arrangement they trust or feel comfortable sending their kids to—even though they both want their kids to learn and thrive in a school setting. The new facility will be welcoming, Lepore-Jentleson says, and the fact that the neighborhood provided input will further help families take part in those services and experience the benefits of early child education firsthand.

Many parents in East Dayton have their own childhood traumas and not all have had a chance to process them, explains Lepore-Jentleson. Without education and intervention, such patterns can be passed along to their children. This is one of the reasons why Lepore-Jentleson is a strong advocate for the two-generation approach, referring to the wrap-around services that benefit both the parents and children.

The two-generation collaborative involves a group of organizations and community leaders that are committed to working together to build systems that take seriously the importance of engaging both parents and children. It provides education, support, access to wrap-around services, and the chance to build community for parents—structures that will allow them to form stronger bonds within the community, take advantage of the services available, and more be present and involved in their own children’s life and education. It begins in early childhood and then goes through elementary school. Lepore-Jentleson’s goal would be to expand the program and support through middle school.

For Lepore-Jentleson, a new Head Start building doesn’t solve everything, but it is an essential piece of the trust, care, and education puzzle. Two-generation programs that focus on early education, like Head Start, as the places where parents can come together and access the resources and community that allow them to build the sort of healthy and stable families that Brandon and Edie work so hard to create. “That’s where the change is going to happen,” she says.

For Edie and Brandon, that change will begin with trust. One thing they are scared of—and continue to come back to in our conversations—is that other people will judge them. They’ve had rough patches in their lives—a stretch of time without a home where they stayed with a relative who was involved with drugs and had a “scary” lifestyle. A time where they were separated from their kids, and then shamed by the local hospital when they went to get help. They have been shamed about jobs they’ve lost, and even have shame about the school situation, where it seems like there is no good option for their children.

But there is no shame connected to the Head Start. To Edie, it seems like a trustworthy option for sending their youngest—and they both acknowledge that a place like that could open up educational opportunities for the entire family. “It’s an option,” Edie admits. “At least for our youngest. I’d be willing to give it a look.”

Acknowledgments

Support for this brief on community engagement and care was provided by the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, which works to inspire and connect individuals and organizations to advance thriving and inclusive democracies around the globe. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation. Excerpts from this piece have been published in the Dayton Daily News and on the author’s newsletter, It Doesn’t Have to Be This Hard.