How People Become Terrorists

Weekly Article

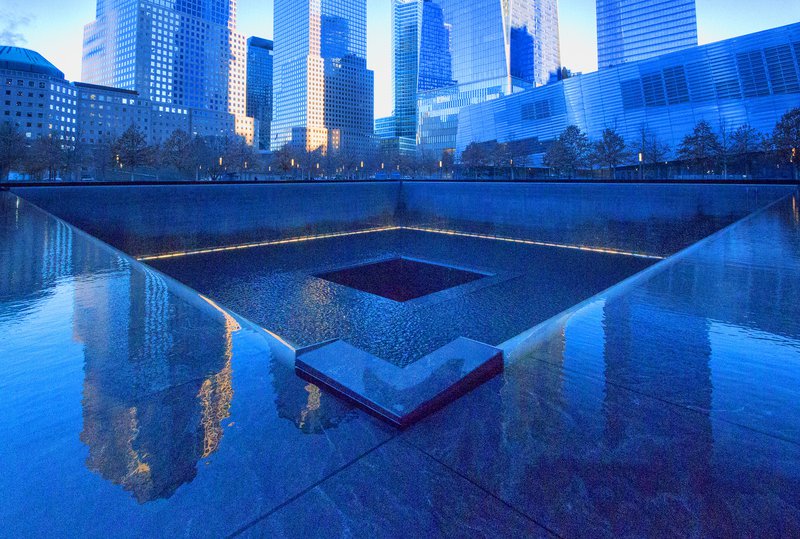

Flickr Creative Commons

March 2, 2017

We may be thinking about terrorism all wrong. Is it an act against something or by someone? Terror expert Marc Sageman would argue it’s an expression of political violence. To divorce it from that context and to try to build a profile of a terrorists based on stable, personal characteristics—such as religion or country of origin—is to continue to make the same mistakes over and over again.

Take, for example, the case of Jamal al-Harith, a British IS suicide bomber who killed himself in Iraq in late February. Born Ronald Fiddler in Manchester, al-Harith converted to Islam in his 20s and traveled widely throughout Muslim-majority countries pre-9/11, before returning to the United Kingdom in 2004. Ten years later he would leave for Syria to join ISIS.

The story could end there, a cut-and-dry case of religious radicalization. al-Harith was picked up by the United States on suspicion of terrorism and spent two years in Guantanamo Bay, leading a former counter-terrorism adviser to the United States to tell the BBC that the death of al-Harith demonstrated the fact that “some of the people in Guantanamo Bay were up to no good.”

But as Sageman made clear, at a New America event Wednesday, that narrative ignores the nuances of what, exactly, political violence is. Sageman argued that the fundamental issue with the way we look at terrorism is that the people studying and observing the phenomenon have never been terrorists, and rarely speak to people who actually commit acts of political violence.

“We define ourselves in contrast to what we call terrorists,” he said. “That means that what we think about when we think of terrorists are really just stereotypes of what we are not.” So our definitions of terrorism not only end up reflecting our own biases against outsiders, but they also fall victim to fundamental attribution error: the human tendency to explain someone’s behavior based on internal factors, such as personality or mental illness, and to underestimate the influence that situational influences can have on another person’s behavior.

The sort of error is why when you forget to return someone’s email, it’s because you were busy. But when someone else forgets, it’s because she’s inconsiderate. It’s the basis for state policies such as no-fly lists and Muslim registries, and it underpins a lot of traditional radicalization studies. And according to Sageman, it points to why profiles of terrorists that rely on characteristics such as ideology, mental illness, or criminal background will continue to be ineffective. Interviews with over 30 perpetrators of violent acts and research covering 34 campaigns of political violence spread over four continents and 230 years led Sageman to propose a new approach to identifying indicators of extremism in his book, Misunderstanding Terrorism.

Yet even with all of this knowledge, the first step to committing an act of political violence is something that we all do: self-categorize. We have a well-researched tendency to make sense of our world by dividing it into social categories, identifying ourselves with others who share our particular qualities (the “ingroup”) and stereotyping those who do not (the “outgroup”). The shift from individual to social identification is what makes collective behavior possible: It’s the basis of both patriotism and systematic racism. Social identities in and of themselves are quick and natural, an emotional and effortless associative process that is neither good nor bad.

The danger lies in when those identities become politicized.

The activation of a politicized social identity starts with a grievance. Sageman used an example of students protesting due to bad food and bad teaching, their passive identity as students now politicized to agitate for change. The grievance creates a political protest community, which is still not inherently dangerous. Most Western liberal democracies were founded through political protest—peaceful or otherwise.

No, the threat of political violence begins not with the protestors, but with the escalation of the conflict by the out-group—in the example of the students, this would be the school administration. If the dean of the school panics and calls the police, who then respond with force against an otherwise peaceful protest, then the conflict is no longer over the food, but the rapid escalation of behavior—and violence. This is why, Sageman argued, it’s impossible to understand al-Qaeda or the Taliban or ISIS without first understanding the colonial and imperialist violence perpetrated by the West that predated those groups.

“The state’s contribution to the emergence of violence is missing from the literature,” he said, adding that it’s partially because the scholars writing the literature tend to identify with the state that’s paying them. The study of political violence has to analyze interactions of both groups involved in the conflict, otherwise we fall into the trap of pathologizing the behavior of a group as an indicator of terrorism.

In the case of al-Harith, his two-year detention at Guantanamo began after he had already spent time in a Taliban prison—under suspicion of being a British spy. When he landed in the hands of American military forces, he thought he had been saved. Instead, they imprisoned him for two years for the sole reason, according to his Guantanamo file, that “he was expected to have knowledge of Taliban treatment of prisoners and interrogation tactics.” His release was recommended within a few months of arriving in Cuba, but he was nonetheless detained because it had been decided that he had been involved in a terrorist attack against the United States—though he had never been questioned about one. Allegedly, he was awarded £1 million in compensation once he was released, on the basis that the British government knew he was being mistreated. But the damage had already been done.

Radicalization continues when ingroup victims have no effective legal redress and start to become disillusioned by the established political process. Political violence, perpetrated by a few who feel like the political machine is moving too slowly, often erupts at the tail end of legal political protest campaigns, explained Sageman. Moral outrage at perceived—or real—egregious outgroup aggression is the next step, followed by the activation of a militarized social identity to protect an endangered political protest community.

The key point here is that all social identities, whether through race or gender or sports affiliation, are vulnerable to radicalization. Political violence is the consequence of human nature, and it requires a constant vigilance to prevent the natural tendency to escalate conflict. It requires states to actively work to keep calm in the face of non-violent challenges and not to confuse legitimate protest with extremism. It requires fair police conduct and an effective means to address real grievances.

It requires, in short, a return to the basic tenets of democracy.