Federal Student Aid

A Background Primer

Blog Post

March 16, 2015

As the price of a college education has risen, an increasing number of students and their families have come to rely on assistance from the federal government to pay for their education. In the last decade alone, after adjusting for inflation, the federal government’s share of all funds used to pay for postsecondary education has grown from 62.3 percent ($93.4 billion) in 2003-2004 to 66.3 percent ($164.5 billion) in 2013-2014.

While student aid in various forms has increased across all sectors—federal, state, institutional—over the last ten years, federal student aid has grown at a faster rate. Between 2003-2004 and 2012-2013, federal student aid through Pell grants increased 109 percent (from $16.1 billion to $33.7 billion). During the same period, state grants for postsecondary education grew only 21 percent (from $7.8 billion to $9.5 billion), and institutional grants grew 92 percent (from $25.2 billion to $48.2 billion).

The mix of aid through grants, loans, work study and tax benefits varies between undergraduate and graduate students, especially in the breakdown between grants and loans. Historically, graduate students have received a larger percentage of financial aid through loans rather than grants, while undergraduates received a larger percentage through grants rather than loans. In recent years undergraduate assistance has shifted toward more loans, largely as a result of the inability of Pell and other grants to keep up with increases in the price of college that well outstrip the rate of inflation.

Types of Federal Assistance for Postsecondary Education

There are four main types of federal assistance for students and their families to fund a postsecondary education—grants, loans, education tax benefits and work study. Of the federal aid available in 2013-2014 for both undergraduate and graduate study, 37 percent was in the form of grants, 50 percent was in the form of loans, 12 percent was in the form of tax benefits and about 1 percent was in the form of work study.

The following table outlines the various federal programs and benefits for financial assistance for postsecondary education.

The remainder of this primer will concentrate on Federal grants, loans, and work study provided under the Higher Education Act. Due to the number and complexity of higher education tax benefits, those are handled in a separate PNPI Primer.

Qualifying for Financial Assistance under the Higher Education Act

Students must first meet certain basic eligibility requirements to receive a Pell grant, federal student loan or other federal financial assistance under the Higher Education Act. These include:

- Be a U.S. citizen or eligible non-citizen.

- Have a valid Social Security Card.

- Be registered with the Selective Service, if applicant is male.

- Be enrolled or accepted for enrollment as a regular student in an eligible degree or certificate program.

- Maintain satisfactory academic progress while in school.

- Have a high school diploma or recognized equivalent.

- Not be in default on a federal student loan nor owe money on a federal student grant.

After meeting these basic eligibility requirements, each student and/or family must complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). The information submitted through the FAFSA helps determine how much federal aid a student may receive. Students are either dependent or independent students when filling out the FAFSA. Applicants who are considered dependent students must provide financial information for themselves and their parents, while those who are considered independent students must provide financial information only for themselves and a spouse if applicable.

A student is considered independent if he or she is one of the following: at least 24 years old, married, a graduate or professional student, a veteran, a member of the armed forces, an orphan, a ward of the court, an individual with legal dependents other than a spouse, an emancipated minor or an individual who is homeless or at risk of becoming homeless.

The FAFSA collects information related to students’ and their families’ adjusted gross income, earnings, untaxed income, assets and investments, receipt of various federal benefits (e.g., SSI, food stamps, TANF, WIC, free or reduced price lunch), as well as information on the number of people in a household and the number of family members in college. Then, a formula set by the government is used to determine a student’s expected family contribution (EFC).

The EFC is an index that is used to measure students’ and families’ financial strength. A lower EFC indicates a greater need for financial assistance toward the cost of college. The EFC is used to determine student eligibility for the need-based federal student aid programs: Pell grants, Subsidized Stafford loans, Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, Federal Work Study and Perkins Loans.

The calculation for determining the amount of need-based aid for which a student is eligible is: Cost of Attendance – Expected Family Contribution = Financial Need

Cost of Attendance is determined by individual schools and includes: tuition and fees; an allowance for books, supplies, transportation, student loan fees and miscellaneous personal expenses; an allowance for room and board; an allowance for dependent care; reasonable costs associated with study abroad (when applicable); and an allowance for expenses related to a student’s disability (if applicable). For students attending school less than half-time, allowances for miscellaneous personal expenses and room and board are not included in the cost of attendance.

Students and families who do not qualify for need-based financial aid or who need to borrow more funds than are available to them through the need-based programs may qualify for the two loan programs not based on financial need: Unsubsidized Stafford Loans and PLUS Loans. The calculation for determining non-need-based aid is:

Cost of Attendance – Financial Aid Awarded So Far = Eligibility for Non-need-based Aid

Pell Grants

The Pell grant is considered the foundation of federal need-based aid for undergraduate students. Among the federal grant programs authorized under the Higher Education Act (HEA), the Pell Grant program is by far the largest, constituting 96 percent of federal grant aid in 2013-2014. The additional, much smaller grant programs authorized under HEA are the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (SEOG), the Leveraging Educational Assistance Partnerships (LEAP), Academic Competitiveness Grants (ACG) and SMART Grants. In recent years, the array of grant programs outside of Pell has shrunk. No new ACG or SMART Grants were available effective July 1, 2011, and lawmakers have not provided the LEAP program with any funding since fiscal year 2010.

The origin of today’s Pell Grant program was the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant (BEOG), which was created by Congress in 1972. In 1980 the BEOG program was renamed the Pell Grant program in honor of Senator Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island. Then, as now, the Pell Grant program provides need-based financial aid to undergraduate students. Unlike a loan, a federal Pell grant does not have to be repaid. The maximum Pell grant awarded for the 2014-2015 academic year is $5,730, with the amount of individual awards determined by financial need, total cost of attending a particular school, and full-time or part-time status.

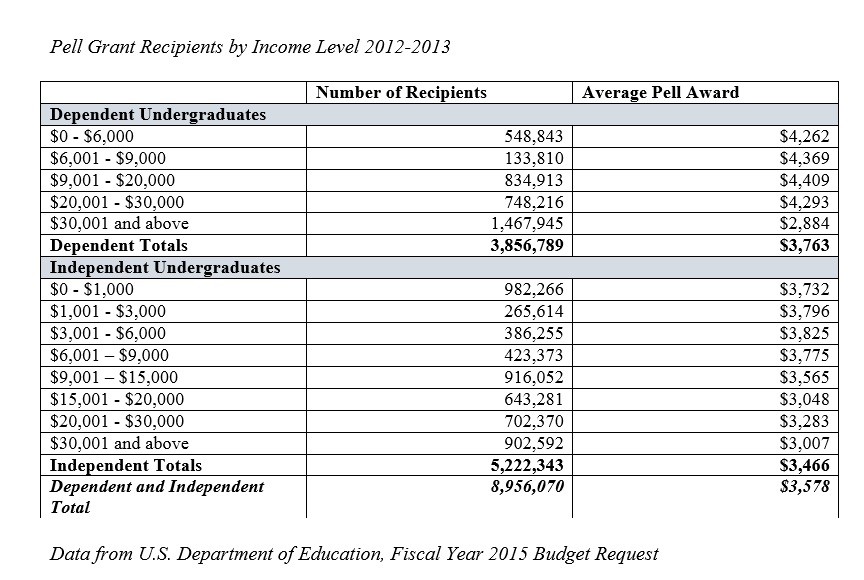

In the 2012-2013 academic year, roughly 8.7 million students received Pell grants and the average Pell grant award was $3,578. The number of recipients declined from a peak of 9.4 million in the 2011-2012 academic year, but the number is projected to grow slightly each future year. Approximately 27 percent of all undergraduates receive a Pell grant that they use at 5,400 participating schools across the nation. Of those receiving Pell grants in 2012-2013, 42 percent were dependent students and 58 percent were independent students.

Beginning in 2008, the number and cost of Pell grants rose significantly. The number of Pell recipients grew 70 percent, from 5.5 million recipients in 2007-2008 to 9.4 million recipients in 2011-2012. The cost of the program increased similarly, by 83 percent from a cost of $18.0 billion in fiscal year 2008 to $33.0 billion in fiscal year 2014.

This increase in the cost of the Pell Grant program was partly due to the downturn in the economy, which sent more individuals back to school and caused more individuals in school to have financial need. In addition, lawmakers made changes to the program in 2007, 2008 and 2009 that expanded eligibility and benefits in the program, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 increased the maximum Pell grant, which Congress has been hesitant to roll back.

To pay for these increasing costs in the Pell Grant program without reducing the maximum Pell grant, Congress has scrambled in recent years to find savings in other federal aid programs and within the Pell program to cover current costs. These savings have meant the elimination of Subsidized Stafford Loans for graduate students, the end of year-round Pell grants which could be used for summer course sessions, a decrease in the income limit to qualify automatically for a maximum Pell grant, and a reduction in the number of semesters for which a student is eligible to receive a Pell grant. At present, no long-term plan has been enacted to address the possibility of further program increases.

However, recent economic and enrollment trends have lessened the budgetary pressure on the program. Enrollment has declined from its peak in 2011 and is expected to grow only modestly going forward, and economic gains have led to reduced eligibility for Pell grants. Moreover, past Congressional Budget Office projections overestimated the program’s future cost. The Pell grant program can therefore be expected to operate at existing levels of appropriations until fiscal year 2017. At that point, it is expected that Congress will need to increase the annual appropriation by $2.3 billion to maintain the existing benefit levels.

Federal Student Loans

Given the ever-rising cost of postsecondary education, students and their families have increasingly come to rely upon federal student loans to pay for college. New federal student loan volume (not including consolidation loans) has risen sharply since 1992 from less than $19 billion in fiscal year 1992 to $101 billion in 2014. As part of the Higher Education Amendments of 1992, Congress introduced unsubsidized student loans—loans not dependent on financial need, which helped drive the increase in loan volume. Further, in the last decade, the percentage of undergraduates taking out federal loans to pay for college has risen.

Stafford, PLUS and Consolidation loans are the Federal government’s three primary loan programs to assist students and parents pay for a postsecondary education. A fourth and smaller loan program, Perkins, is discussed in the following section on campus-based aid programs.

Until recently, there were two federal loan programs for the origination and administration of Stafford, PLUS, and Consolidation loans – the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program and the Direct Loan program. Under the FFEL program, private lenders provided the loan capital to originate student loans. In return, lenders were provided with an interest subsidy as well as reimbursements for most costs of defaults. Under the Direct Loan program, the federal government provides the capital and institutions and private companies contracted by the U.S. Department of Education handle origination and loan servicing. With very few exceptions, the terms and conditions of loans made under the FFEL and Direct Loan programs are the same.

As part of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, the FFEL program ceased making new loans effective July 1, 2010. All new Stafford, PLUS, and Consolidation loans today are made under the Direct Loan program.

Stafford Loans

Stafford Loans are the primary federal student loans and are available both to undergraduate and graduate students. Stafford Loans come in two types – subsidized and unsubsidized.

Subsidized Stafford: Subsidized Stafford loans are based on a student’s financial need. While a student is in school and during grace and deferment periods, the federal government pays the interest on the loan. Until July 2012, Subsidized Stafford loans were available to both undergraduate and graduate students; however, after July 1, 2012, Subsidized Stafford loans are now exclusively available to undergraduate students.

Unsubsidized Stafford: Unsubsidized Stafford loans are available to undergraduate and graduate students without regard to financial need. Unlike Subsidized Stafford loans, the federal government does not pay the interest on these loans while a student is in school. Although students need not make payments on their Unsubsidized Stafford loans while in school, the interest accrues and is capitalized when they enter repayment.

PLUS Loans

PLUS loans are available to parents of dependent undergraduate students (Parent PLUS) and to graduate students (Grad PLUS). Like Unsubsidized Stafford loans, interest accrues on PLUS loans while the student is in school and is capitalized upon entering repayment. Typically, PLUS loan borrowers cannot have an adverse credit history to be eligible for the program.

While Parent PLUS loans have been part of the federal loan program since the 1980s, Grad PLUS loans are relatively new. The federal government began offering these loans to graduate students on July 1, 2006 out of concern that many graduate students, having hit the borrowing limits under the Stafford loan program, were taking out high-cost private student loans to finance their graduate education. Since they were first offered in the 2006-2007 academic year, the annual total dollar amount borrowed, adjusted for inflation, of Grad PLUS loans has grown steadily from $2.4 billion in 2006-2007 to $8.0 billion in 2013-2014.

Consolidation Loans

Consolidation loans allow borrowers to combine all their existing student loans into one loan, thus avoiding the need for multiple monthly student loan payments. Most federal student loans are eligible for consolidation. Private educational loans are not eligible for consolidation.

Loan Limits

Not wanting students to leave school with too great a debt burden, the federal government has set both annual and aggregate loan limits for Stafford loans. Annual loan limits apply to the maximum principal amount that may be borrowed plus any fees that the borrower is required to pay. The aggregate loan limits are the total amount of outstanding Stafford Loan debt (i.e., unpaid principal) that undergraduate, graduate, and professional students may accrue.

Historically, Congress has been reticent to raise Stafford loan limits. The Higher Education Amendments of 1992 increased the annual Stafford loan limits, beginning in the 1993-1994 academic year, for sophomores, juniors, seniors and graduate students, along with increases in the aggregate limits. No additional increases occurred until the 2007-2008 academic year when the Higher Education Reconciliation Act of 2005 increased the annual Stafford limits for freshmen, sophomores, and graduate students, but not the aggregate limits.

The last increase to Stafford loan limits occurred as part of the Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loans Act of 2008 (ECASLA) through which both annual and aggregate Stafford unsubsidized loan limits were increased for undergraduate students, beginning in the 2008-2009 academic year. Although aggregate Stafford limits for graduate students did not increase under ECASLA, in July 2006, Grad PLUS loans became available, thereby opening up additional loan availability for graduate students.

Two special circumstances apply to the loan limits above. Dependent undergraduate students whose parents are unable to qualify for a Parent PLUS loan may borrow at the levels set for independent undergraduate students. Graduate and professional students in certain high cost health profession programs, e.g., medical school students, may have higher annual and aggregate unsubsidized loan limits. The total aggregate loan limit for these students is currently $224,000.

PLUS Loan Limits

Although both annual and aggregate loan limits existed in the PLUS loan program in the 1980s ($4,000 annual; $20,000 aggregate), those limits were eliminated by the Higher Education Amendments of 1992. The annual amount a parent or graduate student may borrow under the PLUS loan program is the cost of attendance (as established by the school) minus any other financial assistance the student has received. There are no total aggregate loan limits under the PLUS loan program.

Interest Rates

The interest rates on federal student loans have changed multiple times over the history of the program. In each case Congress sets the rate, either in law or using a formula based on market interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities (“T-bills”). Originally, the interest rates on federal student loans were fixed. Then in the 1990s, loans other than Consolidation loans carried variable rates (resetting once per year) with interest rate caps. Consolidation loans continued to carry fixed interest rates, and borrowers could convert variable loans to a fixed rate by taking out a Consolidation loan. In the early 2000s, Congress opted to make interest rates on all federal student loans fixed once again, beginning with new loans issued after July 1, 2006. These rates were set by Congress.

Then in 2013, lawmakers enacted a new formula for setting fixed interest rates on federal student loans. Each year, the fixed rate on newly issued loans is set according to a formula based on the 10-year Treasury note. This policy change also established different rates on Unsubsidized Stafford loans for undergraduate and graduate student borrowers. Historically, those rates were always the same. 98

Student Borrowing

As the cost of college has continued to increase and grant aid has not kept pace, more students and their families have turned to federal student loans to finance their education. The number of students borrowing and the total amount they borrow in federal loans on an annual basis has increased significantly in the last decade. Among all Stafford loan borrowers, the number of undergraduate students borrowing has risen from 5.5 million in the 2003-2004 academic year to 7.8 million in the 2013-2014 academic year. The total dollar amount, adjusted for inflation, undergraduates borrowed under the Stafford program in that same time period has risen from $33.3 billion to $51.8 billion. Stafford loans for undergraduates are subject to annual and aggregate limits, which keeps borrowing lower than it would otherwise be. Policymakers have raised those limits twice in the last 10 years.

As the numbers above reflect just one year of borrowing at the undergraduate level, it is also helpful to look at the distribution of student loan balances to see how these add up throughout a student’s higher education. According to the Federal Reserve’s 2012 4th Quarter Household Debt and Credit Report, 40 percent of student loan borrowers have balances that are less than $10,000 and 3.7 percent have balances that are greater than $100,000. These figures reflect all borrowers at any point in repayment, and those who pursued all ranges of education from a certificate program to medical and law school. Some may be recent graduates and some may be about to fully repay their loans.

The distribution of loan balances when borrowers leave school offers another perspective on student debt loads. The most recent U.S. Department of Education survey of postsecondary students provides the best reference for such a measure. It shows that for undergraduates who completed their programs (certificates, associates and bachelor’s degrees) with debt in the 2011-2012 academic year, the median federal student loan balance was $18,000. About 55 percent of students left school with federal student loans. Seventy-five percent of borrowers left school with less $28,742 in federal loan debt. Twenty-five percent of borrowers left with $8,906 or less.

Student Loan Repayment

There are multiple plans available to students and parents for the repayment of federal student loans. These multiple plans cover an array of financial situations during which a borrower may need relief from the amount owed under the standard repayment plan. Under standard repayment, borrowers pay a fixed amount every month until the loan is paid in full. There is a minimum monthly payment of $50 and the borrower has up to 10 years to repay the loan. Alternatives to standard repayment include the following:

Graduated repayment: Under graduated repayment, loan payments are lower at first and then increase, usually every two years, as a borrower’s income typically rises after graduation from college. Like standard repayment, the loan term under graduated repayment is 10 years.

Extended repayment: Under extended repayment, loan payments are either fixed or graduated and may be repaid over a period of 25 years. While extended repayment allows for lower monthly payments, the borrower will pay more in interest since the loan is repaid over a 25-year period.

Income-based repayment: Under IBR, a borrower’s monthly loan payments are capped at 15 percent of the borrower’s monthly discretionary income. Discretionary income is the difference between adjusted gross income and 150 percent of the federal poverty line. If a borrower repays under the IBR plan for 25 years and meets other requirements, the borrower may have any remaining balance of the loan cancelled.

Pay As You Earn: In 2010, Congress passed legislation creating the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) repayment program, which is similar to IBR. Effective December 2012, PAYE lowered the IBR cap from 15 percent to 10 percent and made the remaining loan balance eligible for cancellation after only 20 years. PAYE is only available to borrowers with older loans (those who borrowed before October 2007 or who have not borrowed since October 2011). In June 2014, President Obama signed an Executive Order to expand PAYE eligibility to borrowers with newer loans. These provisions are expected to be implemented by December 2015.

Income-contingent repayment: Income-contingent repayment (ICR) calculates a borrower’s monthly payments each year based on the borrower’s adjusted gross income, family size, and the total amount of loans. The maximum repayment period is 25 years, and if the borrower has not repaid fully after this time, the unpaid portion is discharged. ICR is not available for FFEL loans. It is not available for parent PLUS loans unless the loans are converted to Consolidation loans, in which case they are fully eligible for ICR.

Income-sensitive repayment: Under income-sensitive repayment, a borrower’s monthly payment is based on annual income and payments change as income changes. However, unlike IBR and ICR, the loan term under income-sensitive payment is 10 years. The income-sensitive repayment plan is available only for FFEL loans and does not apply to Parent PLUS loans.

Borrowers may select or be assigned a repayment plan when they first begin repaying their federal student loans. Borrowers can change repayment plans at any time. Scheduled payments are usually made monthly and the amount owed depends upon the type of loan received, the amount borrowed, the interest rate, and the selected repayment plan.

In addition to the multiple repayment options above, borrowers having difficulty with repayment may also be temporarily granted a deferment or forbearance. A deferment is a postponement of payment on a loan that is allowed under certain conditions during which interest does not accrue on subsidized Stafford and Perkins loans. Under forbearance, monthly loan payments are temporarily suspended or reduced, but interest continues to accrue.

If a borrower fails to make scheduled payments on student loans, the borrower is in default. There are actions that the student’s school, the financial institution that granted the loan, the loan guarantor and/or the federal government can and will take to recover the money the borrower owes. These actions include reporting the default to consumer reporting agencies, wage garnishment, offsetting social security benefits for the amount owed, deeming the borrower ineligible for further federal student aid and filing a civil lawsuit.

Finally, to encourage individuals to enter certain, often lower-paying professions, the federal government offers a number of loan forgiveness programs. Included among those programs are Teacher Loan Forgiveness and Public Service Loan Forgiveness. Under Teacher Loan Forgiveness, teachers who teach for five consecutive years in certain low-income schools may be eligible for up to $17,500 in loan forgiveness. Under the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, borrowers who work full-time in certain public service jobs may, after having made 120 payments under certain repayment plans (IBR, ICR, Standard Repayment Plan and any other DL Program repayment plan), have their outstanding loan balance forgiven.

Campus-Based Aid Programs

Outside of Pell and federal student loans, there is a trio of need-based aid programs administered by the U.S. Department of Education and commonly referred to as campus-based aid: Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, Federal Work Study and Perkins loans. Unlike Pell and federal student loans, funds for campus-based aid are distributed directly to participating schools, who then distribute them to students, and these schools must provide matching funds for loans through these programs. Historically, the campus-based aid programs have been very popular among participating schools due to the greater flexibility and control schools have to package this aid for individual students on their campuses.

While schools favor the flexibility of the campus-based aid programs, many believe that the formulas used to determine a school’s allocation are flawed and inequitable. A substantial share of the funds under the campus-based programs is allocated in proportion to what schools received in prior years, not current enrollment of needy students. Funds are first distributed to schools based on what they received as their base guarantee in fiscal year 1999. Newer schools and schools that have experienced growth in their enrollments, especially among students qualifying for need-based financial aid, are significantly disadvantaged by the current hold harmless requirement in the campus-based programs.

Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants

The Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (SEOG) program is among the oldest of the federal financial aid programs for undergraduate students and is one of the origins of the Pell program. Originally simply named the Educational Opportunity Grant, the program was renamed with the Higher Education Act Amendments of 1972.

At present, roughly 3,800 schools participate in the SEOG program. To participate in the program, schools are required to provide a 25 percent match to the federal funds they receive. SEOG funds are distributed among participating schools via a statutory formula, and appropriations for the SEOG program have remained relatively flat over the last few years. For fiscal year 2014, SEOG was funded at $733 million.

The maximum SEOG grant a student may receive is $4,000. As required by the Higher Education Act, schools are to award SEOG funds first to undergraduate Pell grant recipients who demonstrate exceptional need, (i.e., students with the lowest expected family contribution). If any funds remain after meeting the needs of these students, school may then distribute funds to undergraduate students who are not Pell recipients.

In the 2011-2012 academic year, approximately 1.6 million undergraduates (around 6 percent of all undergraduates) received SEOG awards. The average award students received was $588. Among dependent undergraduates, 68 percent of SEOG recipients in 2011-2012 came from families with an income of less than $30,000. Among independent undergraduates, 78 percent of SEOG recipients had incomes of less than $20,000.

Federal Work Study

The Federal Work Study (FWS) program is also one of the oldest higher education assistance programs, originating in the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, then incorporated into the original Higher Education Act of 1965. The FWS program helps students finance their education by providing part-time employment for both undergraduate and graduate students who demonstrate financial need. Under the program, students may work at their school of attendance, a government agency (federal, state, or local), a private nonprofit organization, or a private for-profit organization.

The U.S. Department of Education allocates FWS funding directly to institutions that then select students for employment. FWS funds are distributed among participating schools via a statutory formula. Congressional appropriations for the FWS program in fiscal year 2014 were $975 million.

As with all campus-based aid programs, the FWS program requires a financial match from the institution. Generally, schools and employers must provide 25 percent of a student’s earnings under FWS. For private, for-profit employers the match is 50 percent. Under certain circumstances, the match for private nonprofits and government agencies may be lowered to 10 percent. Student wages under FWS must equal or exceed the current federal minimum wage.

In the 2011-2012 school year, approximately 3,400 schools participated in the FWS program and provided financial assistance to 704,211 undergraduate and graduate students. The vast majority – 92 percent – of FWS recipients were undergraduate students. Among undergraduates, 80 percent were dependent students. The average FWS award in 2011-2012 for dependent undergraduates was $1,605; for independent undergraduates the average award was $1,911; and for graduate students the average award was $2,459.

Federal Perkins Loan Program

The oldest of the campus-based aid programs is the Federal Perkins Loans Program. These loans, originally called National Defense Student Loans, were the first federal student loans and were created as part of the National Defense Education Act of 1958. The loans were renamed Perkins loans in the Higher Education Act Amendments of 1986.

Perkins loans are available to undergraduate and graduate students with exceptional financial need. There are approximately 1,700 schools participating in the Perkins loan program. Like the other campus-based aid programs, schools’ financial aid offices administer the Perkins loan program and have great discretion in deciding the size of a student’s Perkins loan. Schools make Perkins loans out of a federal revolving loan fund held at individual participating schools that consists of federal capital contributions, school matching funds, student loan repayments and reimbursements for Perkins loans public service loan forgiveness.

In the 2011-2012 academic year, the program disbursed $949 million in new loans. About half of the loans were made at private, not-for-profit institutions. Public four-year institutions issued about 45 percent of Perkins loans. Two-year public institutions and for-profit institutions issued less than 5 percent of Perkins loans.

A student eligible for a Perkins loan may borrow up to $5,500 for each year of undergraduate study, and the total a student may borrow as an undergraduate is $27,500. Graduate students may borrow up to $8,000 per year, and the total a student may borrow as a graduate is $60,000, including amounts borrowed as an undergraduate.

Perkins loans carry a 5.0 percent fixed interest rate and the terms are typically more generous than Stafford and PLUS loans. Perkins loan borrowers make no payments and accrue no interest on their loans while in school and during grace and deferment periods. Additionally, borrowers may have their Perkins loans cancelled in exchange for going into certain field of public service including teaching in a low-income school, in content areas of teacher shortages (e.g., math, science, special education), or a HEAD start center; Peace Corps service; working in law enforcement, corrections or as a public defender; working as a nurse or medical technician; or particular types of military service.

In the past, public service loan forgiveness was one of the features of Perkins loans that distinguished them from other federal student loans. However, as public service loan forgiveness options have been added to Stafford loans, the distinctions between the two loan programs have begun to blur, leading some to question the need for separate loan programs.

In the 2011-2012 school year, 484,656 undergraduates and graduate students took out Perkins loans. Of all students receiving Perkins loans in 2011-2012, 86 percent were undergraduates. Among undergraduates, 77 percent were dependent students. The average Perkins loan amount in 2011-2012 for dependent undergraduates was $1,808; for independent undergraduates the average loan was $1,789; and for graduate students the average loan was $2,953.

In conclusion, federal student aid programs have assisted students and their families in paying for college since the 1950s. As the needs of borrowers, the landscape of institutions of higher education and the policy priorities of Congress have changed over the years, changes have been made. A keen understanding of the history and details of these programs can aid policymakers as they consider future changes to the programs.