The Power of Shared Data: Building Blocks for Interoperability

Brief

Viaframe via Getty Images

Sept. 4, 2025

Introduction

Imagine having every tool and dataset needed to turn good intentions into measurable impact and solve complex policy challenges—only to find that they can’t connect or work together. Many state agencies face this challenge. Datasets sit isolated, technical standards diverge, and legal or procedural silos prevent meaningful integration. Without shared access to the data, insights can’t flow, programs can’t scale, and potential impact is left untapped.

This is particularly an issue in higher education state data. Unlike K–12 schools, which are largely state-run, higher education involves public and private universities, community colleges, workforce programs, and state agencies. Without linked systems, tracking students across these diverse institutions is extremely difficult. The disconnected systems are unable to inform programs that would improve student outcomes, optimize public spending, and guide institutions toward greater equity.

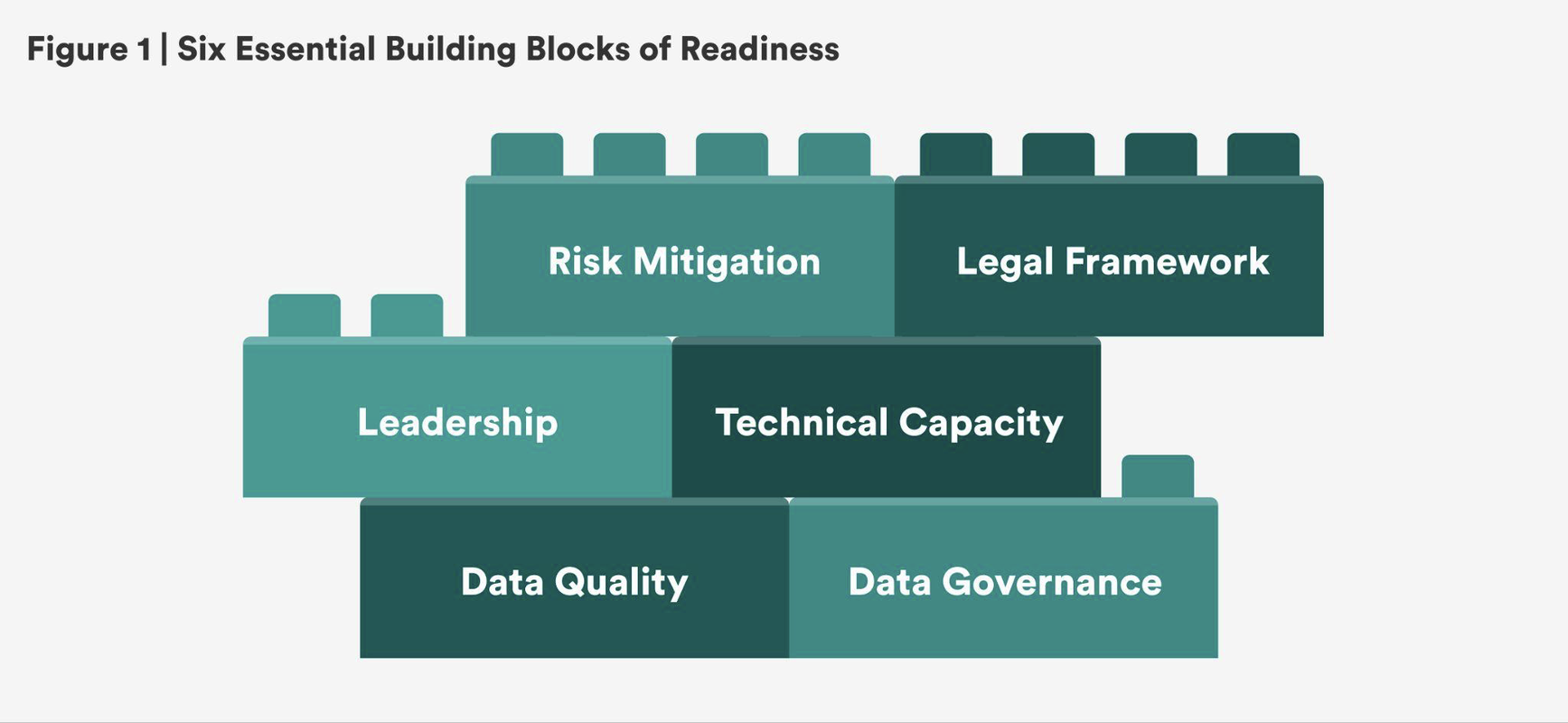

Rather than treating their systems as a collection of isolated parts, agencies can instead approach them as building blocks, with each database designed to fit, stack, and connect to a large structure through shared formats and connective points. This concept, known as interoperability, is the foundation for building systems that can work together effectively.

“Rather than treating their systems as a collection of isolated parts, agencies can instead approach them as building blocks, with each database designed to fit, stack, and connect to a large structure through shared formats and connective points.”

There’s more to this than just making data sharing a priority—true interoperability requires establishing common standards and designing infrastructure so that different databases, tools, and applications can consistently recognize, trust, and interpret one another. It requires structuring data fields and metadata that align across systems and agencies. Most critically, it means viewing data and systems not as a collection of isolated parts, but as a cohesive blueprint that is continually refined.

This brief delineates the challenges and opportunities specific to education data interoperability, though many issues affecting one sector or agency often extend to others. While data is critical to most good policymaking, higher education outcomes—such as graduation, employment, and wage growth—unfold over years or even decades. Disconnected systems make longitudinal tracking almost impossible, undermining policy, funding, and equity analysis, particularly for students who have historically faced barriers. When data flows efficiently and responsibly, policymakers and educators gain a clearer, more comprehensive understanding of who is succeeding, who needs additional resources, and where systemic gaps persist. This understanding empowers targeted interventions that promote fairness, opportunity, and success for all students.

States and institutions are being asked to answer urgent, complex questions: Are public investments translating into real student outcomes? Who is making it to graduation, and who is leaving school without a degree? What happens to students after their studies, and how does that vary by race, income, or geography? The answers can’t be found in a single dataset, or even by a single agency. To fully address them, we need systems that can securely connect education data to workforce, social service, and financial aid data.

Many of our current systems were created before the digital era and weren’t built to support cross-agency interoperability. They were designed to meet internal reporting requirements, not to answer collective questions or adapt to shifting policy demands and technological innovation.

“True interoperability doesn’t start with code—it starts with aligning leadership, legal frameworks, technical infrastructure, and a collective understanding of what good data sharing entails.”

This brief is a guide for how agencies can change that, beginning with readiness. True interoperability doesn’t start with code—it starts with aligning leadership, legal frameworks, technical infrastructure, and a collective understanding of what good data sharing entails. In addition to addressing common barriers, priorities for ensuring readiness, and practical steps to start the process, this brief also introduces a self-assessment tool agencies can use to evaluate their own interoperability.

When done well, interoperability isn’t just efficient—it’s transformative. The goal isn’t to merely replicate datasets and systems or to connect them without a clear purpose—it’s to ensure they fit together in a way that’s useful and sustainable.

Why Interoperability?

Interoperability means the ability to securely and meaningfully exchange data across systems without requiring custom workarounds or constant translation. As Project Unicorn, a K–12 interoperability initiative, puts it, interoperability is the “seamless, secure, and controlled exchange of data between applications.” According to the United Nations’ Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, interoperability also entails the ability to access, process, and integrate data “without losing meaning.” To put it succinctly, interoperability makes data useful beyond its original context.

In practical terms, interoperability means that different databases are either technically connected to each other or structured in analogous ways. For example, while a post-graduate survey can generate some insights into alumni careers, linking student data to workforce outcomes ensures a much larger sample size, allowing the state to better surface disparities and identify necessary changes. Interoperability can also mean ensuring common data formats or standards that align definitions and metadata, enabling different systems to automatically exchange information without manual intervention. For instance, standardized course codes across all levels of education allow K–12 and postsecondary systems to recognize the same course or subject across schools, enabling student progress and achievements to be compared and analyzed consistently. The applications of interoperability are endless: Shared analysis, service delivery, or program evaluation all depend on making sense of fragmented data.

Breaks in the Blueprint: Common Barriers to Interoperability

Agencies and institutions want to make better use of their data. But interoperability can’t be built overnight, and they face real barriers to connecting their data in usable ways. These barriers are more than technical: They’re also institutional, legal, and cultural. Often, they’re hiding in plain sight:

- Legacy systems are one of the most stubborn challenges. Many agencies still run on decades-old infrastructure, patched together to meet past program needs. These systems weren’t designed to connect externally, and vendors don’t always make it easy to change that.

- Manual processes and incompatible platforms compound the problem. From spreadsheets to custom logins, workarounds have piled up in the absence of shared systems. There are often too many tools with too little alignment.

- Data silos are a persistent issue (but not always for the reasons you think). The federal Evidence Act was created to reduce silos and make data more open, accessible, and usable across government. But not all silos are accidental or malicious; data segregation can even be intentional for added safeguards, but these should still be built within interoperable frameworks. Without shared standards or alignment, simply pooling data can still risk duplication, limited utility, and barriers to timely access.

- Legal confusion can be paralyzing. Staff may not know what kinds of data sharing are permitted under federal privacy laws, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). In the absence of clarity, agencies sometimes see inaction as the best way to reduce liability.

- Unclear leadership and misaligned priorities can stall even the best ideas. Limited capacity, unclear authority, and unfamiliarity with new tools can stall initiatives, even when ideas are strong.

- Funding constraints are a common barrier. Interoperability requires real investment in capacity, infrastructure updates, and system updates. Often, a larger initial investment can ensure long-term sustainability and be more cost-effective in the long term than fixing a poorly designed system.

- The lack of a coherent plan is often the biggest obstacle. Interoperability isn’t a feature you tack on at the end—it needs to be part of the blueprint to begin with. Even with the right staff and technical capacity in place, treating coordination as an afterthought can prevent seamless collaboration.

These barriers are real, but agencies can effectively navigate them once they develop high interoperability readiness—that is, the degree to which an organization, agency, or system is prepared to integrate, exchange, and use data across multiple systems securely and consistently.

Defining what “ready” looks like will provide teams with a clear mandate to work across boundaries. The process is more than a technical checklist—it’s a commitment to engaging with the people, policies, and infrastructure that make connection possible.

Prepared agencies and institutions ask questions like:

- Are our systems capable of exchanging data with other internal or external systems without requiring manual workarounds?

- Are key datasets mapped to standardized field definitions and data types across our agency and with sector-wide conventions, ensuring consistent interpretation and integration?

- Do we have metadata and documentation to support shared meaning?

- Do we have formal policies, agreements, or procedures that govern the responsible use and sharing of data, including technical and legal safeguards?

These questions are complex, but agencies that answer them are more likely to have systems that communicate seamlessly, decisions that reflect the whole picture, and data that works as hard as the people behind it.

Designing an Interoperability Framework

A data system is only as strong as its foundation. While you can retrofit a system to be more interoperable, a system that builds it in from the start will be stronger—as long as the fundamentals are correct.

Think of data systems like buildings on a city block. Each building may look different on the outside, designed for its own purpose, but behind the facades, they all rely on the same underlying infrastructure. The plumbing, electricity, and internet system in each building links together across the entire block, feeding back into centralized systems. This is the kind of cooperative infrastructure that interoperability requires. Systems don’t need to be identical or replicate each other’s designs—but they do need to be designed with the greater context in mind.

This brief outlines six essential “building blocks” of interoperability. These key characteristics were identified through a review of interoperability frameworks from multiple sectors—including local government, public governance, social services, and public health—before focusing on those most relevant to education. The building blocks draw from commonly cited frameworks, including the “Project Unicorn Rubric,” UNICEF’s Diagnosis and Recommendations to Integrate Administrative Records Related to Children, Digital Promise’s Data Ready Playbook, and the “Interoperability Maturity Model” from the Consortium of School Networking (CoSN).

These organizations underscore the importance of: (1) data quality, (2) data governance, (3) grounded leadership, (4) technical capacity, (5) legal frameworks, and (6) risk management.

Source: Alex Briñas/New America

These core components make any data system capable of flexing, connecting, and growing across agencies and contexts. They’re the shared foundation that lets agencies align systems without erasing differences—designing not for uniformity, but for compatibility. Adopting these building blocks intentionally is more important than adopting them perfectly.

This brief includes a self-assessment tool to help agencies and institutions take stock of their progress toward interoperability readiness, spot potential obstacles, and map a path forward.

The Six Building Blocks of Architectural Readiness

1. Data Quality

Interoperability only works if the underlying data is reliable. Incomplete submissions, mismatched timelines, inconsistent survey instruments, missing metadata, and basic entry errors can all undermine confidence in shared data. Without reliable, accurate, and well-structured data, leaders risk arriving at misleading and meaningless conclusions. Quality isn’t a one-time achievement—it’s a continuous process of cleaning, removing duplication, validating, and documenting. Tools like data dictionaries, entry-level validation, and automated data transfers improve trust in both generated and shared data. Agencies also benefit from tracking simple metrics, such as the percentage of missing or unmatchable records, to monitor quality over time. That said, the best defense is context: people who know the data well enough to spot issues before they become problems.

How to implement: Start by assessing whether your current datasets actually reflect the questions they are trying to answer. For example, are they reliable indicators of student experiences and outcomes? Prioritize clarity: Inventory what’s in use, identify what’s immovable, and consider how the data was collected. Pay special attention to manual processes, which are often the source of inconsistency. Updating metadata as part of this process also improves interpretability and long-term usability. These initial steps help identify where quality might break down in fragmented data systems. Once that’s accomplished, data users can normalize and recode data where needed, such as aligning inconsistent grading scales or formatting addresses to match across districts.

Case study: The Maryland Longitudinal Data System draws data from six agencies and institutions to evaluate students’ career and college readiness. Early challenges with missing and inconsistent submissions led to the adoption of statewide reporting standards and a data collection calendar, which ensures agencies’ data is chronologically comparable and checked for matching issues before publication. These tools aligned timing, clarified expectations, and set a threshold where review is triggered if more than 10 percent of any variable is missing. Together, they’ve supported a decade of productive collaboration and credible recommendations.

2. Data Governance

Good data governance turns scattered inputs into usable systems that preserve, secure, and transmit data throughout their lifecycle—from collection to access to archiving. Defining the policies, processes, and roles that govern data answers practical questions like: Who updates the spreadsheet? Where do survey results live? Can two datasets be linked over time? For this reason, many agencies adopt a data governance body, policy, or manual that covers topics such as data collection, encryption, and the linkage of data systems. Without governance, agencies risk confusion, security breaches, or tech investments that don’t meet long-term needs.

How to implement: Start by designating data stewards: people responsible for managing specific datasets and ensuring they’re accurate, protected, and shareable. As a guiding principle, these assignees should have intimate knowledge of how various data is collected and interpreted. Their first job should be to audit current practices and align them with relevant standards. From there, they can develop clear protocols for how data is gathered, stored, migrated, protected, and linked. These stewards should also produce guidance or training to help partners comply. As systems evolve, they’ll need to manage vendor contracts and clarify who has the right to access or modify data. Data governance should be focused on long-term outcomes, not just short-term functionality.

Case study: The Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has developed a robust comprehensive public data governance manual. The manual outlines roles across local, state, and federal levels; lays out questions to ask before adding or eliminating a data element; and provides frameworks for linking K–12 and postsecondary data. When the state needed new data on dual language programs, OSPI already had the protocols in place, including a template for a project timeline and a standardized way of collecting student and teacher data. The result: a timely, coordinated effort that provided actionable data without the need to start from scratch in support of Washington’s widespread language immersion programs.

3. Grounded Leadership

Interoperability is often treated as a technical endeavor—but at its core, it is a human one that depends on strong leadership and vision. Lasting progress requires champions who understand the landscape, bridge agencies, and sustain momentum across political cycles. Too many initiatives start with one passionate administrator, only to stall after that person moves on. To endure, interoperability efforts need shared vision, cross-agency coordination, a range of invested stakeholders, and governance structures that outlast individuals. Whether it’s a governor-appointed board, a multi-agency task force, or a working group of district representatives and IT staff, leaders must connect the dots between vision, strategy, and operations. Most critically, they are the people who can communicate the “why” and bring others along.

How to implement: Leaders should start by aligning stakeholders on a clear purpose: a shared perspective on interoperability, core questions to explore in data, and a timeline. What are we trying to answer with this data? Who benefits? What can we feasibly achieve given our environment? From there, they can coordinate with policy and funding bodies, shepherd interagency agreements or legislation, and ensure interoperability is baked into long-term strategic and budget plans. Crucially, strong leaders also make sure that costs and benefits are distributed fairly across participants—especially when resources are uneven.

Case study: California’s Cradle-to-Career Data System brings together 15 stakeholders through a 21-person governing board that includes higher education administrators, state social service leaders, elected officials, nonprofit research professionals, governor and state appointees, and critically, members of the public. The board is tasked with strategic planning, reviewing governance protocols, and elevating community priorities. A key success of the initiative has been the cultivation of data champions who have successfully communicated the importance of data to the public. For example, since 2022, the governing board meetings have been shared on YouTube in both English and Spanish. This cross-cutting and intentional structure—along with its focus on continuity—has been credited with the initiative’s staying power.

4. Technical Capacity

Once leadership and governance are in place, agencies need the technical capacity to connect systems. That includes infrastructure (like student information or learning management systems), integration tools (like application programming interfaces, or APIs), and adherence to shared data standards (like the Department of Education’s Common Education Data Standards, or CEDS). But capacity isn’t just about using the right software—it’s also about having staff who can maintain, troubleshoot, and evolve systems over time.

How to implement: Begin by inventorying the tools currently in use—what they cost, how well they work, and whether they meet program needs. Many agencies are managing thousands of technology tools, often with overlapping or underused features. One nationwide survey found school districts used an average of 2,739 edtech tools in the 2023–2024 academic year, up from 841 in 2018. Clarifying which ones are essential helps reduce bloat, align systems, and map gaps. From there, develop procurement practices that prioritize interoperability, including specs for secure login and scalability. Professional associations like CoSN also stress the importance of tools that protect verified access to platforms through multi-factor authentication (MFA), single sign-on (SSO), and levels of authorized access. As systems evolve, ensure that platforms can scale at pace and that staff are equipped to manage them.

Case study: The New Jersey Education to Earnings Data System (NJEEDS) sparks insights based on tech from the Coleridge Initiative, whose Administrative Data Research Facility provides a cloud-based dashboard for the state to manage data stewards’ profiles, datasets from four state agencies, and project details, along with tools for queries and statistical analysis.

Thanks to this scaffolding, NJEEDS published reports on “wage scarring” post-COVID-19, the impact of scholarships on educational attainment, and post-graduation retention of out-of-state students. The state now has trackable metrics on higher education outcomes that will inform its workshop for 90 higher education institutions in the state. New Jersey is also able to use the platform to share and receive data with others in the Eastern States Collaborative organized by the National Association of State Workforce Agencies.

5. Risk Management

As data flows more freely, so does risk. Interoperability requires strong safeguards to prevent misuse, breaches, or violations of privacy. Risk management isn’t about saying no to data sharing—it’s about designing systems that are secure, ethical, and compliant to protect individuals’ privacy and institutions from harm. While FERPA, HIPAA, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), and state laws protect some of students’ personal information from certain types of disclosure, they are not comprehensive enough to assess risk within an interoperable context.

How to implement: Start by defining your agency’s privacy principles, as modeled by Data Quality Campaign’s Student Data Principles. Then assess current tools and practices through a risk analysis that considers factors like the presence of personally identifiable information (PII), encryption practices, and levels of access. Don’t forget to consider each tool and system in light of changing state regulations. Agencies should clarify who can access what, under what conditions, and with what oversight. More advanced systems may implement statistical disclosure avoidance, automated audits, and breach response protocols. Additionally, everyone—from contractors to internal teams—should receive regular privacy training and operate under clear enforcement policies.

Case study: Indiana appointed privacy officers across various state agencies, along with a chief executive position. These officers track legislative developments, distribute grants for capacity-building projects, audit compliance, and support agency-wide training. Beyond strengthening policies to avoid inadvertent leaks, they’ve also helped vet third-party vendors, ensuring student data isn’t being misused or sold. By building a formal privacy infrastructure, Indiana has both reduced risk and reinforced public trust.

6. Legal Framework

Even the best-intentioned collaboration can’t proceed without the legal scaffolding to support it. Data use agreements (DUAs) and memorandums of understanding (MOUs) are critical tools that define roles, responsibilities, and protections, including the project’s purpose, what PII will be shared, and how access permissions will be distributed. DUAs specify what data is shared, with whom, for what purpose, and for how long. MOUs clarify broader terms—who owns the data, how it will be secured, and how staff will be allocated. Together, these documents lay the legal foundation for safe, purposeful data exchange. They also establish mechanisms for agencies and institutions to assess and ensure that data-sharing partners comply with federal and state law, safeguarding privacy and maintaining trust throughout the collaboration.

How to implement: Use publicly available templates—like those from the Department of Education—as starting points. Tailor them to clarify each party’s obligations, governance roles, and mechanisms for amendment. Legal agreements should connect directly to the data governance structures discussed earlier, reinforcing consistent workflows and compliance. Periodically revisit agreements to reflect changes in law, technology, or policy priorities.

Case study: To better understand outcomes for non-credit students, Missouri built upon an existing data-sharing agreement to request data on students who complete noncredit coursework to better understand employment and performance outcomes for community college students. The state updated an existing MOU between five state agencies to form a new data integration workforce with eight key stakeholders, all of whom fed individual data into a newly designed data warehouse. The revised system enabled the state to collect and aggregate information across many previously unlinked public workforce and higher education systems—ultimately revealing new insights and patterns. As a result, the MoSCORES public dashboard is now available for public use.

From Readiness to Action

Interoperability is a distinct project, but building readiness can start anywhere: in any institution, of any size, at any time. Despite two decades of literature on interoperability in education, identifying where to begin can often be one of the biggest challenges. But the path forward doesn’t need to be complicated. Fortunately, organizations can take several practical steps to build momentum:

Start with the questions. What gaps or opportunities exist in your state’s evidence-based policymaking? What education, workforce, or health questions are leaders wrestling with? What new insights could be gained by integrating data across agencies or states? Reflecting on these priorities helps focus energy on high-impact, achievable projects.

Prioritize easy wins. From that list, identify where you already have momentum. Existing state laws—like those authorizing longitudinal data systems—can make some efforts easier to launch. Target simpler administrative projects and willing partners to establish proof points and build a base for more ambitious efforts down the line.

Fix downstream, think upstream. Ensure consistency and accuracy in how data enters your systems across formats, agencies, and timelines. Early investment in shared standards, secure infrastructure, and clear metadata will make future efforts—like dashboards, visualizations, or cross-agency disbursements—more effective and trustworthy.

Lean into regional collaboration. Communities of practice offer resources, certifications, and shared strategies. The Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools collects case studies and has even published a playbook based on work with 150 school districts in 34 states. The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education operates a multistate longitudinal data exchange for six nearby states. Project Unicorn and CoSN are great options for those seeking to publicly demonstrate their commitment to secure interoperability with credentials. And those not ready to join an interstate governance structure can find meaningful resources in both the Education Commission of the States’ comparative analysis of longitudinal data systems and the Data Quality Campaign’s extensive case studies and policy guides.

Plan for sustainable funding. Interoperability efforts often raise questions about long-term costs, especially for technical infrastructure and staffing. While pandemic-era aid sparked historic investment in edtech, many of those grants are sunsetting. Agencies can still find support across federal, state, and subject-matter lines (though funding availability is subject to change).

Within the public sphere, the Office of Management and Budget Partnership Fund Pilot has supported data system upgrades for enrollment and case management. The Institute of Education Sciences’ 10 Regional Educational Laboratories partner with state education departments on programs and research to improve student outcomes, offering both funding and technical support. In addition, the National Center for Education Statistics disseminates grants through the Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems Grant Program, with a focus on efficiency, resource allocation, and labor market results. And education agencies aren’t the only source—the Department of Labor’s Workforce Data Quality Initiative funds states’ efforts to connect workforce and education data in longitudinal databases.

Private grantmakers are stepping up, too. The Gates Foundation is investing in bolstering interoperable systems so students nationwide gain valuable postsecondary credentials, and it helps fund Coleridge Initiative’s Democratizing our Data Challenge, which supports states, postsecondary institutions, and research organizations in building accessible, secure, and scalable data infrastructure. From studying unemployment claims to teacher vacancies, the project promotes cross-stakeholder engagement. The State Education Fellows program from Results for America also supports data-driven decision-making by local program leaders, many of whom have launched multi-agency collaborations serving students in vulnerable conditions.

Operationalizing Readiness: A Self-Assessment Tool

To move from planning to implementation and actually operationalize the building blocks, agencies and institutions need a clear sense of where they are, where the gaps lie, and what’s needed to move forward.

The diagnostic tool below is designed to help agencies surface existing strengths, identify areas of growth, and prioritize next steps. It is not necessarily a checklist to complete, but a practical framework for reflection, coordination, and action. Whether launching a new project or improving an existing one, these questions can help teams align their strategies and structure their efforts.

Conclusion: Building Interoperability That Lasts

Whether an agency is examining students’ paths into high-demand careers or tracking university retention, it doesn’t need to start from scratch. Understanding common barriers and investing deliberately in foundational building blocks can transform interoperability from a distant ideal into a practical reality. Even where this is a new endeavor, readiness is attainable. It spurs systems to connect thoughtfully, securely, and with purpose, unlocking collective impact to better serve students and communities. In the end, interoperability’s power does not stem from the technology—it stems from the people using these tools so collaboration yields results.

Editorial disclosure: This brief was supported by the Gates Foundation. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and are not intended to reflect the views of the Gates Foundation or New America.