The Rise of Youth Cybercrime: Social Trends and Interventions

Brief

Leon Neal via Getty Images

Oct. 21, 2025

This brief explores the evolution of youth cybercrime as both a social and technological phenomenon. It differentiates between cyber-enabled crimes (such as fraud, phishing, and identity theft) and cyber-dependent crimes (including ransomware, botnets, and zero-day exploitation), demonstrating how the barriers to entry for both have been radically lowered by artificial intelligence (AI) and resulting crime-as-a-service (CaaS) platforms that offer hacking tools via subscription model.

Through case studies, the brief illustrates the speed, coordination, and scale of youth involvement in cybercrime today. These incidents are not isolated but part of a broader trend that includes social onboarding pathways, peer-to-peer recruitment, and reputation-based ecosystems that transform curiosity into participation, and participation into escalation.

Research shows that youth cybercrime is often motivated less by ideology and more by boredom, frustration, peer prestige, and social isolation. In many cases, offenders are victims of circumstance, groomed into illicit networks through gaming platforms, Discord servers, and Telegram channels—making social influence the primary driver of escalation.

Policy responses must therefore go beyond punishment. The brief examines promising diversion and rehabilitation programs ranging from government responses to the private sector. These approaches pair accountability with technical training, mentorship, and prosocial belonging, offering youth a way out of the criminal pathway while preserving valuable cybersecurity talent.

Introduction

Cybercrime is no longer confined to the margins of criminal behavior. It is emerging as a social movement, particularly among youth. While the average age of arrest across all crimes in the United States is 37, the average within cybercrime drops to 19. Additionally, while general crime rates have been decreasing since 2013, the incidence of cybercrime is increasing. This disparity reflects a profound shift in how technology mediates identity, community, and deviance for younger generations. Over the past decade, the pathways into cybercrime have multiplied and accelerated, shaped by gaming platforms, online forums, new communication tools, and AI. What might begin as a search for customizations in a video game or engagement in a Discord server can quickly evolve into recruitment on Telegram, participation in cybercriminal forums, and ultimately involvement in large-scale, technically sophisticated cybercrimes. In many cases, this trajectory unfolds without the individual fully understanding the gravity of their actions until law enforcement intervenes.

This brief examines the evolving landscape of youth cybercrime, placing it within social, cultural, and technological contexts. It considers the shift of cybercrime from a niche activity carried out by technologically skilled individuals into a criminal trend accessible to large numbers of young people. AI has lowered the technical barriers of entry, enabling youth with minimal expertise or awareness to engage in increasingly complex attacks. In 80 to 90 percent of cases, these individuals are not motivated by ideology or organized sponsorship, but rather by social networks, peer influence, status, or even opportunism. In 55 to 75 percent of cases, belonging is listed as one of the main motivations.

The following sections trace this evolution across multiple dimensions. The brief begins with recent cases that demonstrate the scale and severity of youth involvement in cybercrime, before exploring how cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent cybercrime have been reshaped by AI. We then go over a brief historical overview that places contemporary youth cybercrime within a decade-and-a-half trajectory of social and technological change. Next we look at recruitment pathways, the influence of political and activist movements, and the social and psychological factors that shape participation. Finally, we turn to law enforcement, regional interventions, and private and public rehabilitation models, asking how societies can respond to a social and operational shift in cybercrime with deep financial, social, and emotional consequences.

Youth cybercrime cannot be treated as an isolated matter in criminal justice. It must instead be recognized as a broader redefinition of identity, belonging, and power in a digital age. It is an evolution that carries risks not only for institutions or economies, but also for the life trajectories of young people and the societies they form.

What Makes a Cybercrime or a Cybercriminal?

Traditionally, cybercrime is split into two domains: cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent.

The cyber-enabled category encompasses a range of attacks that, in essence, are still human but enabled in new venues by technology. These crimes have a physical counterpart, such as financial or identity theft, and have moved into the digital realm, making them more pervasive and easier to execute on a global scale. Common online scams—an email telling you to click here, send money there, or “Please reply to this email with the one-time code sent to your phone”—are examples.

The cyber-dependent category is a type of crime that cannot exist without technology. These are activities that traditionally require deeper technical knowledge to carry out, like creating ransomware, botnets, zero-day exploits, and modular rootkits. These types of attacks used to be a lot harder to build and propagate because they require a sophisticated level of coding and other skills, but they are now much easier due to AI tools. And there is little an average victim with few technical skills could do to respond or prevent.

In youth criminal cases, many offenses depend on AI tools to simplify creation, execution, and propagation of both cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent attacks. These tools remove many of the technical barriers that once required more specialized knowledge, meaning that more youth are able to take part in sophisticated cybercrime, often without fully understanding the gravity of what they are doing. In many cases, they become both victims of organized cybercrime and perpetrators.

Mutating Old Patterns

The following cases illustrate the speed, coordination, and cross-platform dynamics characteristic of present-day cybercrime operations, many of which involve teenagers or young adults. They are presented not to sensationalize but to show the operational reality that policies and prevention or rehabilitation strategies must address.

The 2020s have seen the emergence of more extreme and sophisticated forms of youth cybercrime. The following are a few notable examples.

In May 2025, Jasim Shahnawaz Ansari, an 18-year-old from India, was arrested for orchestrating cyberattacks against more than 50 Indian government entities. Part of a youth cybercrime group on Telegram known as “AnonSec,” Ansari planned and carried out distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks using hacking software from GitHub. He was investigated as a terrorist by the Gujarat Anti-Terrorism Squad.

In 2023, Arion Kurtaj, an 18-year-old from the United Kingdom who started hacking at the age of 11, was sentenced to a secure hospital for life after he was discovered to have conducted a hack that cost Rockstar Games thousands of hours of staff time and $5 million. He was part of the Lapsus$ hacking group alongside other teenagers, including a 17-year-old convicted at the same time. The BBC reported that the gang “used con-man-like tricks as well as computer hacking to gain access to multinational corporations such as Microsoft, the technology giant, and digital banking group Revolut.”

Perhaps most notorious of all, Scattered Spider emerged in 2022 as a criminal group largely consisting of teenagers. It has since made headline after headline for cyberattacks and was recognized as a threat actor by multiple law enforcement agencies internationally. The group is a prime example of the evolving culture of cybercrime, combining various levels of technical capability into coordinated attacks and extensively involving youth in their activities. A recent spree cost hundreds of millions of dollars to U.K. retailers Harrods, the Co-Op, and Marks & Spencer. In July 2025, three teenagers and a 20-year-old, from the United Kingdom and Latvia, were arrested as suspects of Computer Misuse Act offenses, blackmail, money laundering, and “participating in the activities of an organized crime group.”

According to a 2022 report by University of East London researchers, about half of European youths ages 16 to 19 reported engaging in online behavior “that could be considered a criminal offence in a jurisdiction (e.g., money muling, hate speech, hacking, fraud, nonconsensual sharing of intimate images).” Another study found that nearly 50 percent of all cyber fraud suspects belong to the 19 to 24 age group, and the occupation most commonly linked to cyber fraud is that of “students,” making clear that this trend in youth cybercrime is not a niche topic or even limited to a discussion of crime. It is a social movement, redefining what it means to exist in a world where technology is pervasive and showing how a lack of digital literacy can result in unknowingly getting involved in criminal activity.

Taken together, these incidents highlight the need to clarify what constitutes a cybercriminal and cybercrime. Understanding how criminal activity online proliferates and expands beyond skills and technological limits requires distinguishing between cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent offenses. This distinction, especially as it’s currently defined by the European Parliament, provides a lens for analyzing where and how capability, access, and intent have shifted.

A Brief History of Cybercrime Since 2010

The 2010s saw the rise of cybercrime as a global business. Smartphones, digital currencies, and the complete digitalization of businesses, such as through the implementation of cloud technologies, opened the door to anyone becoming a victim or a perpetrator. Ransomware, botnets, and denial-of-service attacks became commonplace, and governments began deploying the first true digital weapons. In the first few years of the decade alone, the Zeus Trojan virus stole over $70 million from U.S. banks, Sony data was breached, Edward Snowden shared revelations about spyware, and Adobe’s move to the cloud led to the credit card information of 38 million users being leaked online. Actors also began developing more advanced weapons in geopolitical conflicts: The Stuxnet worm attacked nuclear plants in Iran in an operation suspected to come from the United States and Israel, and hackers linked to the Chinese military seized intellectual property from Google during Operation Aurora. These high-profile incidents signaled the beginning of the next phase of cybercrime and its growing enmeshment with daily life.

None of the aforementioned attacks nor the ones listed below were necessarily conducted by teenagers, but they contributed to cybercrime as a form of social culture. Other cases were clearly defining turning points of a shifting movement:

- CryptoLocker, 2013: This was the first widely known ransomware operation to combine social engineering and botnets successfully. It created the foundation for mixing cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled cybercrime.

- Ashley Madison leak, 2015: This case showed people how data can be leveraged for attention and public appeals.

- TeleCrypt ransomware, 2016: Gamers and their messaging platforms, like Telegram, became used as a key to ransomware proliferation for the first documented case.

- Coinhive, 2018: Instead of using machines just for network traffic, this type of attack also used their processing power to mine. Processing power has since become an important factor in the developing age of AI-assisted attacks. This incident showed how much other people’s computers can be leveraged—far more than a DDoS attack ever could.

Little has changed in this trend of cybercrime’s growing impact except for the speed and scope of what these groups can do. These structural shifts coincided with the mainstreaming of machine learning and, more recently, generative AI. The result is not only more volume, but a qualitative change in tactics. AI augments cyber-enabled crime at scale and simultaneously lowers the skills threshold for cyber-dependent activity, directly fueling the youth cybercrime concern. The next section details these dual effects.

Artificial Intelligence as Fuel

AI comes into play in two distinct ways, each mapping onto the two cybercrime domains mentioned before.

The most discussed impacts of AI on cyber-enabled attacks are how it boosts existing methods with only a small component of innovation. AI enhances the effectiveness of traditional cyber-enabled crime methods, often by automating tasks or personalizing outreach to a previously impossible degree of speed, frequency, and specificity. According to the 2024 report Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on Criminal and Illicit Activities released by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Many traditional criminal activities are made more effective through the use of AI technologies. For example, spear phishing becomes more convincing with AI-generated personalized emails, and market manipulation can be executed more efficiently using AI algorithms to analyze and exploit financial data.”

This is expected. Every sort of fraud, phishing scam, and straightforward extortion or sextortion is generally considered cyber-enabled because AI accelerates the frequency and scope of these attacks but does not fundamentally change the nature of the crime. As the domain provider .Bank put it: “While established hackers are already enjoying these benefits, AI continually lowers the barriers to entry for new criminals entering the fray. In other words, AI can justifiably be seen as a free recruitment tool for hacking syndicates. After all, no technical skills or expertise are required to become a hacker. In 2024, the only prerequisites are having a computer, maintaining internet access, and exercising a duplicitous moral code.”

AI’s impact on cyber-dependent attacks is where true operational shift lies and where there must be more attention. This is where the barriers of entry into cybercrime are lowering, where attack methodology is shifting, and who bears responsibility is more uncertain than ever. Unfortunately, there is far less awareness and research available about these AI-enabled methods, partly because they are newer and partly because their nature makes it difficult to determine direct impact and attribution, even more so than for traditional non-AI cybercrime.

One example is AI-powered malware-as-a-service (MaaS). AI-driven software once existed only in the realm of academia and corporate research and development, but now there are several publicly available plug-and-play MaaS offerings. MaaS parallels the broader model of CaaS, which has transformed hacking into something similar to software-as-a-service, targeting individuals, governments, and companies as clients.

Once a capability is “as-a-service,” progression depends less on skill acquisition and more on social onboarding. MaaS and CaaS make it possible for complex effects to be achieved by users with minimal skill, in particular when coupled with AI. Cybercrime operators mine mainstream gaming, chat, and streaming ecosystems for novices who can be nudged into illicit workflows.

Where does a trend like MaaS fit in with their growing youth cybercrime problem? Use of such services has resulted in the breach of tech giants like Microsoft and Nvidia, as was done by the Lapsus$ group, some of whose attacks at the time were done by a then-16-year-old. Within ransomware services alone, groups like these have been tracked and ranked by performance and innovation.

AI and MaaS platform infrastructure create the conditions for scale, and recruitment mechanics determine who crosses the threshold from curiosity to conducting crimes. Against this backdrop, youth involvement is not an outlier but a predictable downstream effect.

How Teens Get Drawn In

Teenage cybercrime is nothing new, but it is growing in numbers, and the scale, scope, and reach of an individual’s attack moves faster now. In 2011, a study from Michigan State University linked youth hacking not to pathology or curiosity, but to social dynamics. The profile of a teenage hacker had shifted from the curious, creative, often loner genius to the kid with too much time and in the wrong friend group. It is the digital version of falling in with the wrong crowd and finding it hard to get out, except the crowd might be on three different continents and never show their faces. According to a study published in 2023 from researchers affiliated with the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, “Over the past decade, there has been a decrease in crime rates of traditional [non-technical] crimes, while cybercrime rates are on the rise.” Combined with unprecedented technological advances and adoption, there emerges a problem without clear solutions.

With cyber capabilities commoditized and automated and skill barriers reduced, the decisive variable becomes social onboarding: who is reached, persuaded, tasked, and retained.

Youth attackers are typically not sponsored by a government or driven by ideology. Instead, they’re often motivated by boredom, peer prestige, or small financial incentives. At times, they have no real motivation at all and instead find themselves as victims of circumstance and accidental affiliation—social influence within forums or otherwise innocent chat groups. The distinction between curiosity-fueled pranks and large-scale criminal activity is becoming blurrier.

Initial contact typically occurs in public spaces, like gaming forums or livestream discussion threads, but durable and consistent participation often migrates to higher-trust, invitation-only forums. This progression reflects a move from low-barrier experimentation to task-oriented collaboration, accompanied by tighter social norms and reputational incentives.

Based on observations completed for this research across forums and discussions with people ages 18 through 30 from North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, a common interaction is that a kid goes online asking for help with something, maybe on a gaming platform or a messaging app such as Discord. Other times, young people are offered assistance without soliciting. Their path from curiosity to crime generally looks like this:

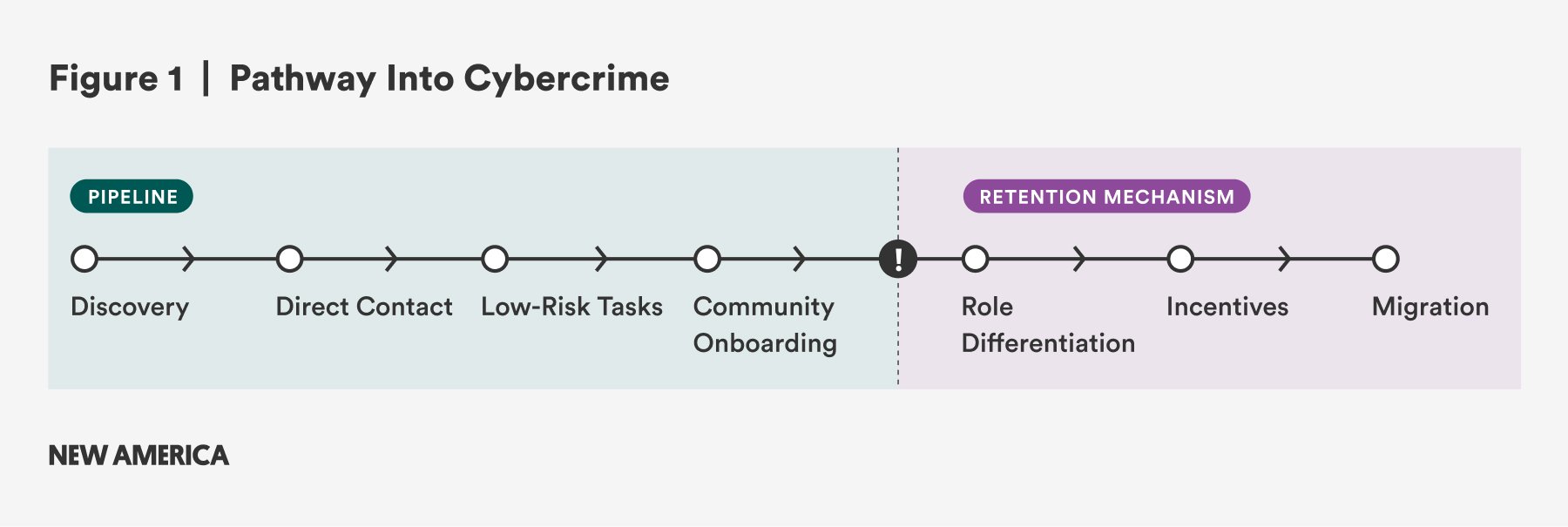

Source: Alex Briñas/New America

- Discovery: A user seeks help, mods, or customization, or is approached in public channels by cybercrime group recruiters.

- Direct Contact: Messages move the exchange off-thread, and small scripts, links, or tools are shared. The purpose or impact of these may or may not be disclosed.

- Low-Risk Tasks: Simple, low-skill assignments are given to the targeted user to establish responsiveness based on engagement with what was shared in the previous step. These could be very basic, like distributing links or running something locally. Some do not get involved beyond this point.

- Community Onboarding: Access to semi-private groups is granted to the targeted user based on their proof-of-work activity or referral by a vouched member.

From there, recruiters implement retention tactics to reward and reinforce the sense of belonging. In these later steps, the mission or purpose becomes more defined:

- Role Differentiation: If the targeted user is active and successfully engaged in the community, they may be sorted into roles ranging from technical to social engineering and recruitment.

- Incentives: Reputation build-up, recognition, and shout-outs for the individual reinforce their sense of identity and belonging.

- Migration: The recruit moves to invite-only chats or platforms with stricter verification and vouching, which usually have higher impact tasks. This completes the full recruitment and retention process.

Transitioning from open platforms to invite-only forums reconfigures the binding constraint from technical competence to social endorsement. Entry is governed by vouching, reputation, and demonstrated reliability rather than pure technical skill. Once curiosity is converted into responsiveness, recruitment shifts from visibility to selectivity. The following section examines the shift beyond open Discord and Telegram channels into high-trust ecosystems that professionalize roles and raise reputational stakes.

Recruiting Beyond Discord and Telegram

Some observers of cybercrime believe that the endpoint of recruitment is Discord, chats on Twitch and Kick, or open-access Telegram channels where they will receive simple instructions to run a script or open a file (on Telegram specifically, Android app files can be attached directly to messages, sometimes disguised as other types of files). This is particularly true for targets who will only be used to run a prepackaged toolkit that could conveniently implicate youth for a crime they may in fact be clueless about. For the more talented recruits, connecting on public platforms is the entry point.

Recruitment for higher-skilled teens shifts communication platforms to places like BreachForums and XSS (both of which are evolving) as well as other niche, invite-only cybercrime channels spread across the surface web, the dark web, and apps like Telegram. These are often older channels, sometimes in their second, fifth, or even 10th iteration after being taken down over and over, or purposely migrating and purging members. They cultivate continuity through vouching for members, holding assets in escrow, and curating how-to-participate playbooks. Teenagers still make it here, invited by a friend or a recruiter, showing off an attack they conducted but barely understand and are praised for it, or receive whatever cocktail of social interaction their post warranted.

Whatever the case, these spaces offer a sense of belonging or purpose. They value initiative and critique and offer starter tasks that often have lower technical complexity, intended to test some form of loyalty and openness to risk as well as technical potential. Tasks range from setting up simple phishing schemes or running software locally to launching full-scale cyber attacks. Success increases recruits’ access; failure carries reputational penalties. Over time, participants move from trivial, low-complexity tasks to coordinated roles. For example, one participant may start out running preexisting software without much interaction and later become a dedicated recruiter, malware writer, or information gatherer. AI-enabled content and tooling are assumed baselines, lowering the skill threshold for executing attacks while prioritizing social alignment.

Although the pipeline described above primarily feeds profit-seeking criminal markets, teens may also be recruited through civic, ideological, or wartime narratives that similarly project the feeling of belonging to a larger movement. These mechanics of recruitment also include vouching, tasking, operations security norms, and reputation, but the framing shifts from “jobs” to “missions,” and targets are justified as serving a political or humanitarian cause. For teenagers already primed by status signaling and low-friction tools that don’t require much training, the same onboarding mechanics that professionalize criminal roles can mobilize volunteers for campaigns presented as collective action.

In the collective action ecosystem, groups have a clear political drive, like the IT Army of Ukraine, which uses evolving cyber methodologies and recruitment tactics. This IT Army is a formal movement of Ukraine formed in 2022 following a declaration by Mykhailo Fedorov, then Ukraine’s deputy prime minister and minister of digital transformation. While the group started as more exclusive in its official recruitment, it has drawn the attention of non-Ukrainian contributors across all ages, including crowdsourcing projects such as DDoS kits reportedly created and contributed to by non-Ukrainian citizens. In some notable cases, U.S. citizens, motivated by ideological alignment, have physically joined the Ukrainian Army; this motivation can easily extend to cyber volunteers. When considering the rising involvement of youth in cyber operations and the challenge of differentiating their involvement from that of adults, it brings further into question the social and legal implications of crimes committed, knowingly or unknowingly, while conducting combatant operations.

Fail the Crime, Fail the Person: Programmatic Responses to Cybercrime

If pathways into cybercrime are social and developmental, effective responses should be, too. This section focuses on identifying intervention points across the recruitment cycle and reviewing programmatic responses, from diversion and skills-redirection to structured rehabilitation.

The cases mentioned at the beginning of this brief—Ansari, Kurtaj, and members of Scattered Spider—show a range of responses from different regions and distinct intervention points. Organizations have attempted to formally lay out different intervention points for cybercriminals; CREST, for example, considers a spectrum of legality from legal general digital interest to illegal serious cybercrime. Points of intervention range from raising awareness of online social responsibilities to developing resources such as coding clubs, positive marketing activities within hacking forums, and advocates’ demonstration of skills in the community.

As CREST stated in a presentation about cybercrime prevention: “A criminal justice system should be able to provide exit routes from a cyber criminal pathway, particularly if an individual has been identified as suitable for an offender prevention intervention after they have been arrested, prosecuted, and/or imprisoned.”

Punishment alone does not stop reoffending, nor the often lifelong cycle of offense, prosecution, punishment, and recidivism. While there is a recognized need for rehabilitation options, online offenses generally lack this across regions, particularly in the case of cyber-dependent crimes that do not have a non-technical counterpart. One key historical difference for cyber-dependent crimes compared with other types of crime is that they traditionally required strong technical skills. The evolution of cyber-dependent crimes that can be attained with lower technical skills now creates a self-reinforcing effect: The pool of youth offenders is widening at the same time that opportunities for redirection into legitimate work and workforce training remain inaccessible. Reintegration into society through legitimate employment after rehabilitation has also historically been challenged by the existence of a criminal record. In some countries, such as the United States, a number of employers exclude individuals with criminal records from their hiring processes.

Some countries, however, have launched initiatives that aim to divert potential or caught cybercriminals. Ian Glover, then-president of CREST, stated that “these initiatives work best when they are integrated with those that demonstrate proper career paths, and that you can earn as much, if not more, on the right side of the law.”

Authorities in the Netherlands have developed the Hack_Right program, an alternative criminal justice program for young first offenders of cyber-dependent crimes. The project was planned in 2018, and shortly after, began a pilot implementation targeting young offenders between the ages of 12 and 23. In an evaluation of the program, researchers at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement noted: “The police and Public Prosecution Service saw a large influx of (young) computer crime suspects and noticed that these suspects had a different profile than usual crime suspects. Cybercrime suspects were suggested to be younger, not aware of the consequences of their behavior, and to have more intrinsic motives.”

The program contains four components: recovery, training, coaching, and alternatives. Despite high levels of satisfaction reported from the implementers themselves, the satisfaction of offenders varied, with the key complaint being that assignments were too easy and that the overall objectives were unclear. Implementers also noted that participants were not initially open to supervisors or that supervisors found it difficult to “move into [the offenders’] world of experience.” In the worst cases, participants were critical of supervisors and saw them as annoying because of their lack of understanding. Yet despite these reviews, only one participant out of 18 claimed to not have benefited from the program.

In the United Kingdom, intervention panels are now being piloted for cyber-dependent criminals specifically. The targets are those who have been assessed as capable of causing significant harm, and they have to be referred to the program by a parent or guardian, an educator, an officer, or a judge. A panel of professionals then reviews the individual’s personal circumstances and helps determine what intervention is appropriate, contrasting with the Dutch approach, which strives to create a more universal pathway that can be followed by offenders. U.K. intervention may consist of mental health support, social skills development, further education, and access to an online portal where participants can develop their technical skills and directly connect with potential employers. More so than the Dutch approach, the United Kingdom aims to address the underlying causes of criminal intent and preserve talent for future redirection.

In the nongovernmental and private sectors, projects such as Immersive Labs’ Cyber Million or Virtue and HaptAI (Hacking Aptitude AI recruitment platform) from The Hacking Games are attempting to address the issue before a crime is committed, connecting young hackers-to-be with clear pathways to mentorship and employment. Although these programs have attracted investment and involvement from the community (and in the case of The Hacking Games, partnerships with large companies and public or regional organizations like ECSO), their tangible impact has yet to be comprehensively measured.

Overall, public or public partnership programs that pair accountability with capability-building and prosocial belonging show great promise.

Recommendations and Conclusion

The demographics of cybercrime and emerging prevention programs have practical implications for a whole-of-society strategy that treats youth cybercrime as a cultural and developmental challenge, not merely a technical or legal one. Policy responses and recommendations include:

- Governments should pair accountability with rehabilitation by creating clear diversion programs beyond punishment that offer structured recovery, technical training, and mentorship to reduce reoffending and redirect talent towards legal pathways.

- Education systems, and even families, should embed digital literacy, ethics, and cyber hygiene into learning from an early age, emphasizing not only skills but also the social or legal implications of online actions.

- Communities should expand opportunities for youth to engage with cybersecurity in positive ways, such as coding clubs, Capture-the-Flag competitions, and mentorship programs, creating status and belonging outside illicit ecosystems.

- Lastly, in at least some of the environments mentioned above, mental health and social support must be integrated into interventions, recognizing that many offenders act under conditions of isolation, frustration, or undiagnosed conditions.

In the longer term, law enforcement must adapt to evolving tactics and recruitment methods, adopting proportionate, developmentally informed responses that avoid unnecessarily criminalizing low-level first offenses and focus instead on identifying patterns, offering exit routes, and targeting organized recruitment networks. On the side of academia and private entities, there should be dedicated research on AI-enabled cybercrime to stay ahead of emerging risks, ensuring that preventive strategies evolve as quickly as the methodologies and tools themselves.

We cannot afford to treat cybercrime as a niche problem of the criminal sphere, especially when it comes to youth. It is a pervasive cultural movement riding on the back of technological advancements, lower barriers to entry, and an unprecedented redefinition of what it means to live a “human” life. The actions that lead to it are increasingly becoming insidious and commonplace. The consequences are social, financial, and emotional, and can completely change the life trajectory of both victims and perpetrators. If we continue to view youth cybercrime solely through a lens of punishment, we risk pushing an entire generation further into illicit networks where belonging, status, and income can be found more easily than in legitimate institutions.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my peer reviewers, who wish to stay anonymous due to the nature of their work; Will McKeen and The Hacking Games team; and Bridget Chan and the team at New America.

Editorial disclosure: The views expressed in this brief are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views of New America, its staff, fellows, funders, or board of directors.