Protecting Student Parents from Evictions: A Q&A with Eddy Conroy and Nick Graetz

Blog Post

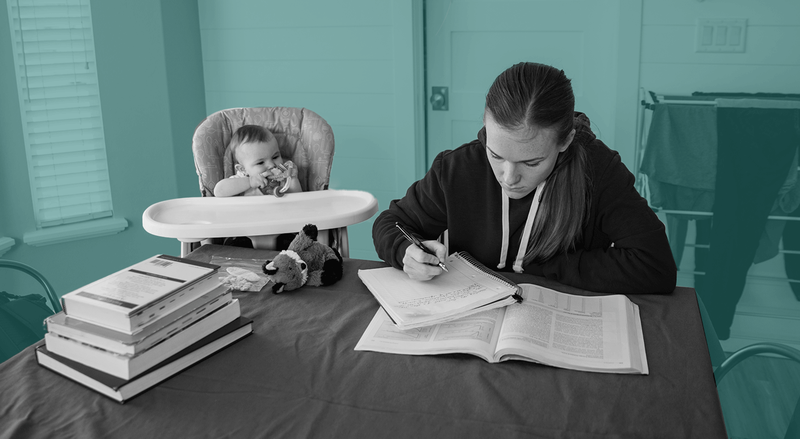

Alex Briñas/New America

July 29, 2025

This article is part of The Rooftop, a blog and multimedia series from New America’s Future of Land and Housing program. Featuring insights from experts across diverse fields, the series is a home for bold ideas to improve housing in the United States and globally.

New America’s Yuliya Panfil sat down with higher education expert Eddy Conroy and Eviction Lab researcher Nick Graetz about their study on student parents and eviction. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Yuliya Panfil: Hello and welcome everybody to The Rooftop. My name is Yuliya Panfil and I’m the Director of New America’s Future of Land and Housing program. The Rooftop is a housing blog and multimedia series hosted by our program and shaped entirely by its contributors. The Rooftop is a forum for individuals and organizations across the housing sector to share innovative ideas, big or small in scale, public or private, well-trodden or experimental.

And today, we’re so excited to be joined by eviction researcher Nick Graetz and New America’s own Eddy Conroy. Nick is an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota in the department of sociology and at the Institute for Social Research and Data Innovation. And he’s affiliated with Princeton’s Eviction Lab. Eddy is a senior policy manager on the Higher Education Policy team here at New America. Nick and Eddy teamed up to release a groundbreaking study that looks at the impact of evictions on parenting students—that is, college students who are themselves parents.

And today, we’re talking about what they found and what their findings mean for both the fields of housing and education. Welcome Nick and Eddy.

Eddy Conroy: Thanks so much for having us.

Nick Graetz: Yeah, thanks for having us.

Panfil: Nick and Eddy, you’ve just released this first-of-its-kind study that looks at the impact of evictions on parenting students. How did you choose to focus on this specific population?

Conroy: So New America’s Higher Education team has been working on student-parent issues for almost four years now, largely to try and bring more of a federal policy focus to the more than 3 million undergrad students who are parenting while they’re in college, plus almost another million graduate students. And what sparked the collaboration with Eviction Lab was a report that they published in late 2023, if I remember correctly, that showed families with young children were at highest risk of eviction.

And as part of our body of work on parenting students, we’ve been trying to build collaborations with different advocacy fields, other folks working on different policy areas, because parenting students cross so many different policy and advocacy areas. They interact with child care, with the K–12 system, with housing, in a lot of different ways that not all students do. And so the study in 2023 from Eviction Lab showing families with young children being at highest risk of eviction got me wondering whether it would be possible to look at what happens to a parenting student who’s enrolled in college and then receives an eviction filing.

It seemed fairly intuitive that it would probably harm college success, but we were interested in knowing how big of an impact it could have on those outcomes, and that’s how we ended up being introduced to Eviction Lab and starting to work with Nick.

Graetz: Yeah, and I’ll just add that the study Eddy mentioned in 2023 was the first of this big collaboration we’ve set up with the U.S. Census Bureau to link eviction records to other forms of Census administrative data, because eviction records themselves only contain names and addresses. So to really study this population and look at outcomes, we have to do this data linkage.

As Eddy mentioned, the upshot of that study was we found that households with kids are twice as likely to be evicted as households without kids. We wanted to dig into specific types of households with children, but also wanted to collaborate with folks already doing this work. So the collaboration with New America was natural, given all the expertise and work they’re already doing in the parenting student space.

Panfil: And what did you find in this study?

Graetz: So the study allows us really for the first time to examine the demographics of parenting students threatened with eviction. While we know that parenting students are older on average than non-parenting students, we actually found that parenting students threatened with eviction tend to be younger.

And we also found huge racial disparities. Black parenting students make up just 20 percent of all parenting students, but 57 percent of those threatened with eviction. And then besides just describing who is affected by this, we can also look at outcomes for students both by parenting status and eviction filing status. For parenting students threatened with eviction, we found that their likelihood of completing their degree is roughly half that of parenting students not threatened with the eviction. So we find that just 15 percent of parenting students threatened with eviction finish their bachelor’s degree.

We also find that parenting students threatened with eviction tend to have much lower incomes, measured post-enrollment, and also much higher risk of death in the 10 years post-enrollment. And this is consistent with a lot of other work we’ve now published using this linked data on this really tight association between eviction and mortality risk. We’re not able to dig into the exact mechanisms in this study, but this is likely the accumulation of lots of things, including the direct acute impacts of eviction, as well as the difficulty it can introduce in terms of things like finding new stable housing, new employment, things like that.

“Parenting students threatened with eviction tend to have much lower incomes, measured post-enrollment, and also much higher risk of death in the 10 years post-enrollment.”

Panfil: Thanks, Nick, and I’m going to throw a surprise question in here that we haven’t discussed, but hopefully you can touch on quickly. I think that a natural question back when seeing this study is asking to what extent this is a function of correlation—so the same parenting students who are likely to experience an eviction also have some other factors that would make them likely to not graduate at the same rates, or be coming from poverty and so not having similar post-graduate income. How do you respond to that question?

Graetz: Yeah, it’s a great question. And I think that certainly does play a role here. So we’re not estimating the causal effect of the eviction filing itself in this study. We’re just looking at outcomes across parenting students who are filed against in housing court versus those that aren’t.

But something we’re able to do because of all this data linkage is we can make those comparisons in pretty tight groups, so we can adjust for ways that you mentioned that these populations are going to differ systematically. So demographics like age, race, sex, but we’re also able to measure incomes. We’re able to measure the income of the parents of parenting students to try to get at some of those pathways of, “Are these students sort of already disadvantaged in certain ways coming into college enrollment?” And we still see these really big differences in outcomes, like degree and the other things we’re looking at.

So I think it’s always going to be tough to tease apart exactly what is the eviction, per se, and what is kind of the snowballing effect of other things that are happening at the same time that parenting students might find themselves in housing court. I think something we focus on here is that this is sort of how housing court, and the point of being filed against for eviction, represents a really critical time of crisis for parents experiencing really severe housing insecurity. And [it] can serve as potentially a really important point of intervention.

Panfil: Thanks for explaining that, Nick. So if I’m understanding correctly, while you’re not able to establish causation, to some extent, the robustness of the dataset you’re working with is allowing you to isolate the eviction variable and compare very similar groups, with the only difference being that one has experienced eviction and the other has not.

Graetz: Exactly, that’s the goal. So we’ve tried to rule out some of the obvious differences like income, age, things like that.

Panfil: Thank you. So Eddy, how do you interpret these findings?

Conroy: So there’s a couple of things. Something we know pretty well from other research by places like Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Urban Institute, and Child Trends is that parenting students, in spite of the huge number of responsibilities they juggle, do pretty well academically. Even though they are usually working full-time, they’re trying to take classes, they’re juggling child care responsibilities, they still tend to have similar, even slightly higher GPAs than their non-parenting peers. But we also know that even under the best of circumstances, taking what we’ve looked at here, with eviction out of the equation, they’re much less likely to complete than their non-parenting peers. So there’s a lot of evidence to suggest that it is non-academic challenges like dealing with housing issues that are what’s throwing parenting students off course.

And the findings that we have here, I think, make it really crystal clear that failing to ensure parenting students have safe and stable housing means they’re very unlikely to complete a degree. There’s been prior sort of survey-based research to suggest that that’s accurate. But as Nick was talking about, as far as we’re aware, this is the first time we’ve had millions of records. This is not across the whole country, but we have a number of states, 12 million records to work with, that make it clear that if you don’t ensure that parenting students have safe, secure, stable housing, it’s going to be really, really hard for them to complete a degree and find sort of long-term economic security, not just for them, but most importantly for their children.

“If you don’t ensure that parenting students have safe, secure, stable housing, it’s going to be really, really hard for them to complete a degree and find sort of long-term economic security, not just for them, but most importantly for their children.”

And so part of this is, lots of the work on parenting students shows that if parents are presented with a choice between getting to class, finishing their degree, or making sure that there’s food on the table and that there is a roof over their kids’ heads, they’re going to choose that [the latter] every time, as I think almost anybody would. And so every time we put a barrier like housing in front of parenting students who are striving to provide economic security for them and their children, we’re undermining the investment in helping them pay for college, because they’re less likely to complete. We’re making it more likely over the long run that those families rely on some kind of public support, which is really counter to the whole goal here that if we help these students get to the finish line, as you see from the income numbers five years post-enrollment, where families who weren’t threatened with eviction have really good family income, it’s very clear that if we can get parents past that point, they’re probably going to do pretty well.

And so we are not only, by failing to prevent eviction in these cases, harming those students immediately, but this then becomes a two-generation problem [where] we are probably harming the long-term outcomes of those students’ children as well. And so working on these problems, the harms are multigenerational, but if we can find solutions, the benefits can be multigenerational too.

Panfil: Yeah, that’s a really great way to just sum up how high the stakes are at this very fulcrum moment for these parenting students and their families. So last question to both of you—these findings are coming at a time where the Trump administration is slashing eviction protections and much of our safety net is in question. What do you see as any promising ways to stabilize the housing needs of parenting students? And who is responsible for enacting those protections?

Conroy: Something that has been a really good thing over the past 10 [or] 15 plus years is higher education has focused more and more on basic needs issues and the reality that you are going to find it more difficult to succeed in college if you’re worried about where your next meal is coming from, whether you have a safe place to sleep at night. And that has led to good things, like colleges thinking more about connecting students with benefits and finding innovative ways to provide emergency aid and things like that. But it also means colleges and universities have slowly been asked to become social service providers in lots of ways they were never designed for. At least in part because our public safety net system is really damaged and that is about to get far worse based on what’s happening in Congress, unfortunately.

And ultimately, this isn’t a problem that colleges and universities can solve by themselves. They have done, in many cases, lots of good work to improve their focus on basic needs. But we need colleges and universities to be able to work with their local public housing authorities, with housing advocates at the state and local and even federal level.

Probably this gets outside of my area of expertise, and I’ll let Nick maybe speak to it a bit more, but zoning reform for more dense construction. I actually think what has just happened in California literally in the past two days of potentially bringing down some barriers to more dense building could be really interesting to watch. We know the housing affordability crisis isn’t something that just impacts parenting students—it’s a broad problem we need to fix—but it does seem like, at least from what this research shows so far, parenting students seem to be uniquely vulnerable as a group to what happens if they suffer an eviction. Nick might have some other thoughts he’d like to add in there.

Graetz: Yeah, I think I agree with all of that. And I would also just add that I think there’s lots of ways universities can help their students that don’t involve necessarily intervening on the housing market. So one big point of emphasis in eviction prevention work is providing legal counsel in housing courts. Tenants are not guaranteed counsel; most tenants are unrepresented—the vast majority— in housing court. And we have a lot of data that when tenants are represented, they’re way, way more likely to retain their housing. So I think we can think about programs on that side of things the universities can potentially invest in, such as really well-funded legal services for their students.

But then I agree with what Eddy mentioned, that there’s sort of these larger housing problems outside of universities. So there’s zoning around college campuses, there’s the increasingly consolidated ownership of student housing, and potential market concentration problems, that creates things like setting high rents. Those are larger issues. But universities tend to be pretty big influential political actors in those spaces, especially locally, and I think can take a much more active role in trying to shape those decisions in ways that can protect students from things like eviction, but especially parenting students.

Panfil: Well, that brings us to the end of our recording. Thank you so much Nick and Eddy for taking the time to share this amazing work with us and thank you, everyone, for listening.

Remember, if you have a housing innovation that you’re interested in either writing about or speaking about, please reach out to FLH@newamerica.org. Thanks so much for listening.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in the articles on The Rooftop are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policy positions of New America.

You May Also Like

The Harsh Reality of Parenting Student Homelessness (Education Policy, 2024): Richard Davis Jr. and Eddy Conroy argue that policymakers need to do more to ensure success for the hundreds of thousands of college students who have children and are experiencing homelessness.

Better Housing Data is Vital. This HUD Report Shows a Path Forward. (Future of Land and Housing, 2025): Sabiha Zainulbhai unpacks recent Trump administration decisions that threaten to worsen housing insecurity—and why better data is part of the solution.