Completing the Housing Innovation Loop: From Policy to Product Entrepreneurs

Blog Post

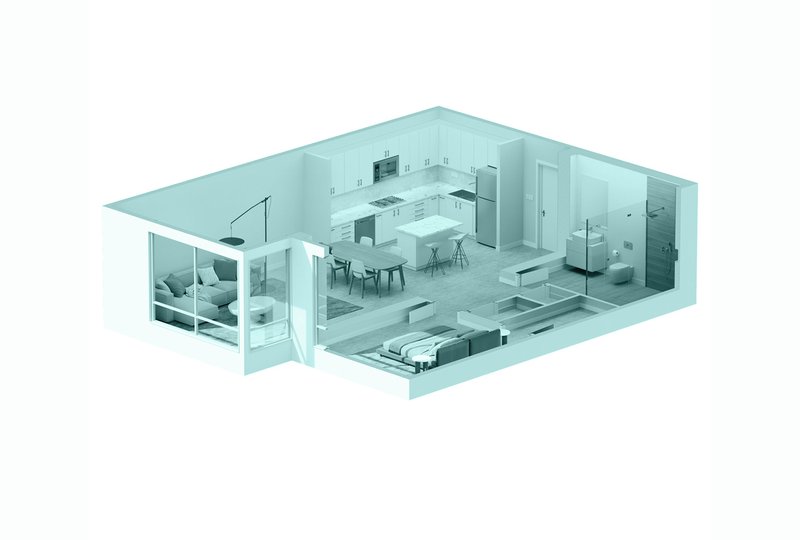

Cloud Apartments; Bronwyn Lipka/New America

Oct. 21, 2025

This article is part of The Rooftop, a blog and multimedia series from New America’s Future of Land and Housing program. Featuring insights from experts across diverse fields, the series is a home for bold ideas to improve housing in the United States and globally.

Construction costs for multifamily housing have risen by more than 25 to 40 percent since 2019, and in places like California, building a single affordable apartment can now exceed $800,000 per unit. These numbers underscore a simple truth: Housing is foundational infrastructure, yet extremely slow and expensive to deliver.

America’s fragmented regulatory framework is a major culprit, as Benjamin Preis explained in a recent article for The Rooftop. With 39,000 municipalities, 10,000 permitting authorities, and a patchwork of local codes, Preis argued, we need more policy entrepreneurs, leaders who can untangle this fragmentation and advance legislation that clears the path for developers.

“Policy without product yields frameworks with no delivery. Product without policy and connective infrastructure yields technical innovations trapped in isolated pilots, often unable to scale.”

But policy reform alone can’t close the country’s 7.1-million-unit housing supply gap. Even in the most supportive regulatory environment, the development process remains burdened by inefficiency, risk, and cost. To translate policy progress into built homes, we also need product entrepreneurs—innovators developing repeatable, scalable systems that turn policy opportunity into real-world housing delivery.

Beyond Policy Reform: Innovating Housing Delivery

To understand the interdependency of policy and product, consider what it takes to actually build one apartment building—a complex, multi-stakeholder endeavor. First, you need a parcel of land. Once the land has been identified, you need to follow the local jurisdictional laws and get it entitled. Then, you need to hire a team of architects, engineers, builders, land use consultants, and lawyers, among others to help you permit it. Once permitted, the land becomes what developers call “shovel ready.” But there’s more: You then need to bring in capital to finance the multi-million dollar property and guarantors to ensure completion. Once construction is complete, and the building has received a Certificate of Occupancy, you need to lease up. To make progress on solving the housing crisis, innovation must happen across this entire development value chain.

Policy without product yields frameworks with no delivery. Product without policy and connective infrastructure yields technical innovations trapped in isolated pilots, often unable to scale. In the U.S. market where housing is privatized, these two roles need to work in conjunction to address the housing shortage.

The Rise of Product Entrepreneurs in Housing

Housing product entrepreneurs are organizations or individuals that invest their capital to identify repeatable, scalable ways to design, finance, and build housing.

Approaching housing development as more than a one-off project, housing product entrepreneurs conceive of it as a repeatable, modular, configurable system that can be adapted across contexts. For example, Cloud Apartments, where I serve as the chief operating officer, delivers housing through a standardized building system with an IKEA-like assembly process that can be configured across various parcels of land with multiple floor plans. They provide their architectural design to developers and use local partners across the entire development value chain (factories, general contractors, and sub-contractors) to complete multifamily buildings at a lower cost than site-built construction.

A growing cohort of product entrepreneurs is tackling different bottlenecks across the housing value chain, each distinct in focus, but united by a shared set of characteristics:

- Repeatable, not one-off: They create a core standardized product line, system, or “kit of parts” that can be reused and also adjusted for different sites or needs.

- Villa Homes has designed a catalogue of ADUs that it partners with local factories to build for consumers. Factories co-locate labor and negotiate national supply chain contracts to drive costs down, making Villa’s ADUs cheaper than site-built construction.

- Kit Switch provides ready-to-install apartment interiors (kitchen pods or bathroom pods) to build housing faster.

- Component modularity: They use building blocks that fit together—systems made from parts that connect easily, so you can mix and match without starting from scratch.

- B.PUBLIC produces panelized components (including walls, roofs, and floors) that can be combined to form many different building types.

- Constructed in controlled settings: They move as much work as possible into predictable, efficient environments, instead of doing everything on-site or one deal at a time.

- Reframe Systems sets up mobile micro-factories near projects to cut transport time and costs.

- Local adaptation through configurable templates: Their products are built to adapt to different codes, climates, or community needs.

- Infilla’s platform adapts to each city’s zoning and entitlement rules, auto-configuring workflows and data fields without requiring custom software builds each time.

- Digital tools that connect design and delivery: They use technology to link various processes together, such as planning, pricing, and permitting.

- Algoma is an AI feasibility tool that’s streamlining the parcel evaluation and design process into a quick analysis to save costs.

- Scalable business models: They pair their product innovation with ways to fund and deliver it at scale through quality partnerships or repeatable financing.

- San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund (SFHAF) operates less like a traditional lender and more like a fintech product company for housing. Its model focuses on building financial tools that can be deployed repeatedly across developments (such as the Industrialized Construction Catalyst Fund, which provides flexible loans for modular projects). Rather than funding one project at a time, SFHAF is creating scalable financial infrastructure for affordable housing.

Policy Fragmentation as a Catalyst for Product Innovation

Product innovation is often borne from policy fragmentation. Because every jurisdiction has different rules, housing innovators have had to build products that can flex across them. This has led to the rise of standardized building systems, adaptable financing tools, and digital platforms that absorb regulatory complexity.

But fragmentation can only take innovation so far. It limits scale. If policy entrepreneurship advanced in the way Preis describes—by harmonizing codes, streamlining approvals, and creating reciprocity between jurisdictions—product entrepreneurs could redirect their energy from adaptation to acceleration.

Policy and Product Entrepreneurship as Complementary Forces

When policy entrepreneurship is thriving, public agencies shape markets through what they choose to reward. When housing finance programs or state funding competitions give additional “points” to projects that use cost-saving or industrialized methods, they de-risk innovation. For product entrepreneurs, this incentivization would enable faster adoption of standardized building systems because it would unlock money for developers leveraging their models without being penalized for trying something new.

Similarly, this dynamic of policy and product entrepreneurship applies to building regulation. The Cloud Apartments system already works across multiple factories, but every new site requires its own approvals, inspections, and interpretation of the same design. If state or regional agencies created reciprocity for proven systems, Cloud Apartments and other similar organizations could deploy at scale instead of one project at a time. Policy entrepreneurship in that sense isn’t rewriting codes; it’s about aligning them to let existing products travel farther.

The Convergence of Imperative and Opportunity

The U.S. housing market has reached an inflection point where need intersects with opportunity:

- Labor and cost pressures are intensifying. Labor shortages, material inflation, and unpredictable supply chains make the inefficiency of bespoke building painfully apparent, preventing housing development at the speed and scale required to address the worsening housing crisis. The numbers remain stagnant. The total number of housing starts in 2024 was just 1.36 million; the year before, 1.42 million.

- Policy momentum is rising. New legislation is emerging at the local, state, and federal levels addressing the many roadblocks across zoning, codes, finance, and more. The landmark bipartisan federal ROAD to Housing Act seeks to increase the housing supply and reduce costs by decreasing regulations, updating federal housing programs, and encouraging communities to adopt policies that support housing. Maryland’s HB 538 makes it easier to build multifamily housing in more places if some affordable units are included. California’s SB 79 overrides local zoning limits to allow for higher density residential projects located near transit stops in highly urbanized counties. The list goes on. All around the country, states are introducing new legislation to ease long-standing constraints to housing development.

- Capital infrastructure is forming around innovation. The SFHAF, with new investments from Apple and Sobrato Philanthropies, has launched the Bay Area Housing Innovation Fund to finance projects that can be built 40 percent faster and cheaper.

- Innovation networks and accelerators are supporting product builders with capital, connections, and market access. The Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Terner Labs has expanded their work to connect policy, research, and industry, building the connective tissue that policy entrepreneurship needs to thrive. The NY Center for Offsite Construction is building an accreditation program for careers in offsite construction to churn more product entrepreneurs.

This convergence of rising costs, new funding, and institutional attention makes now the moment to link policy and product innovation. The task is to industrialize not just how we build, but how we organize, aligning capital, design, and delivery around shared standards. When every link in the value chain innovates together, we’ll move from one-off promising pilots to a scalable system to close the housing gap.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in the articles on The Rooftop are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policy positions of New America.

You May Also Like

We Need More Policy Entrepreneurs to Solve the Housing Crisis (The Rooftop, 2025): Policy entrepreneurs are in a unique position to support innovation in housing, argues Benjamin Preis, founder of Urban Research Advisors.

Funders Should Stop Obsessing over Scale (The Rooftop, 2025): Ruby Bolaria Shifrin of Terner Labs writes that fixating on spreading housing solutions nationwide can distract from smart regional thinking.