Making Wealth Work

Blog Post

Aug. 7, 2007

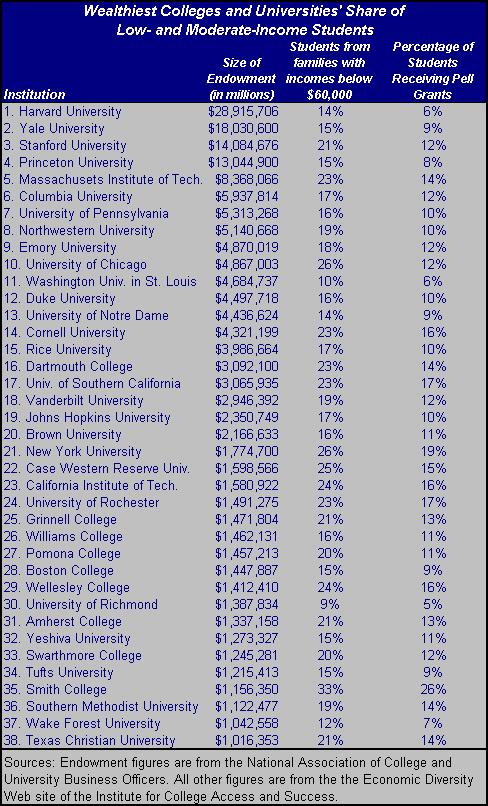

Last week, we discussed the paucity of low-income students at the country's wealthiest colleges and universities. We offered a proposal that would require the richest private colleges to devote a portion of their yearly endowment income to help increase the socioeconomic diversity of their students. Some might argue that there aren't enough qualified underprivileged students to meet such a goal. But as the experience of one top college shows, economic diversity is achievable so long as colleges are willing to make the effort.

The large number of low-income students at Smith is no accident. For years the college has made a concerted effort to attract, enroll and retain less affluent individuals by using funds from its endowment. In 2006 alone the school spent $36.7 million for this purpose.

Despite its success, Smiths efforts have been largely overshadowed by flashier, yet ultimately less effective, programs at Ivy League schools. In 2004, Harvard University, for example, eliminated the requirement that parents contribute to their children's education if they make less than $40,000 a year (later increased to $60,000). This seemed like a promising way to increase socioeconomic diversity, especially for a university with just 14 percent of its students coming from families at or below this income threshold. Yet, despite some rave reviews (and imitation by other Ivies), its effects, at least initially, have been modest. The number of students coming from families making less than $40,000 increased from 6.6 percent of the class of 2008 to 7.9 percent of the class of 2009, a difference of 20 students. Researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research found this to be a noteworthy increase, but Harvard still has a long way to go to match Smith's success.

While eliminating family contributions is quite costly, other schools have elected to replace all loans in the financial aid packages they offer with grants, allowing students to graduate essentially debt free. In 2001, Princeton became one of the first schools to enact such a program, spending an additional $16 million out of its endowment to replace loans with grants for students of all income levels. But two years later, only 8 percent of the students Princeton had enrolled received Pell Grants and just 15 percent came from families with incomes below $60,000.

Given the similarities of these efforts, why was Smiths program so much more effective? Unlike Harvard and Princeton, Smith went out of its way to market itself specifically to less affluent students so it could increase its applicants from the the lower half of the countrys family income distribution. As Daniel F. Sullivan, the president of St. Lawrence University, put it in an article on this subject, "Colleges cannot admit those who do not apply in the first place."

Are low- and moderate-income students not applying because they don't have the grades or test scores that will gain them entry into the hallowed halls of the most elite colleges? Or are these institutions just not looking hard enough for eligible applicants from these income groups?

A 2005 study from economists at Williams College suggests that qualified low-income students are "out there" for the taking. The Williams researchers found that more than one-third of students who scored above a 1300 on the SAT's or the equivalent on the ACT exam came from families making $50,890 or less. Just under 30 percent of those who scored 1420 or above came from those families.

According to the Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance, a group that advises Congress on student aid policy, there are an estimated 170,000 low-income students that are qualified enough to go to college each year, but never will because of cost. Granted many of these students would not be eligible to attend the most selective colleges. But for those that could make it, clearly just improving financial aid is not the solution.

Reducing cost is important, but colleges and universities have to be more proactive about recruiting and targeting low-income students. They have to convince less affluent individuals to apply, give them a fair chance at being admitted, and assure them that an elite education can be made affordable. Creating socioeconomic diversity is an attainable goal, as Smith has shown, but schools need to be ready to make the effort and use a portion of the growth in their endowment funds to make it happen.