Debating China's AI Path: ‘Alternative Routes,’ or ‘Overtaking on the Curve’?

Researchers weigh state-led development vs. market-driven efforts for AI in China

Blog Post

Denys Nevozhai / Unsplash

Nov. 12, 2019

This article was published as part of the Stanford-New America DigiChina Project's first special report, AI Policy and China: Realities of State-Led Development. Read this article and the others in PDF here.

Chinese strategists in AI fields are well aware of their country’s limitations. In May 2019, at the China International Big Data Industry Expo, Chinese Academy of Engineering Academician Gao Wen gave a keynote speech identifying four advantages and four shortcomings in China’s AI development. Among China’s advantages, Gao said, were strong policy support, ample data, rich application scenarios, and many young people with potential talent. Gao identified shortcomings in: basic theoretical research and original algorithms, core AI components, open source platforms, and high-end talent.

Chinese planners had already summarized these shortcomings in the State Council’s 2017 New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (AIDP). Gao’s address suggests that China has made little significant improvement in the two short years since then when it comes to areas such as basic research, algorithms, or core AI components. Having acknowledged these weaknesses, the question before the Chinese AI community now is to address them.

China’s AI development, like its other state-led science and technology development initiatives, attempts to combine “innovation-driven development strategy” with “top-level design.” The Chinese government has led the drive to lead the global AI sector by 2030, under a changing set of campaigns, from “intelligent manufacturing,” first mentioned in the Made In China 2025 strategy in May 2015, to the Internet Plus strategy of July 2015, which listed AI as one of 11 key action areas, to the 2017 AIDP.

While cheering the progress that Chinese AI efforts have made in such a short time, some Chinese scholars and industry experts have recently debated whether a state-run system is best for AI development and what alternatives could be better. Two recent examples illustrate the lively dialogue in China about how best to foster development of AI.

Top-level Design vs. State-run System

China’s state-run system has created incentives that hinder innovation, argued scholars in the China AI Index 2018 report, jointly published in March 2019 by the Center for AI and Institutions (CAII), part of the prominent Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, and the Big Data and Cloud Computing Lab of Wuhan University.

At the report release conference, experts pointed out that Chinese researchers published at least as many AI research papers as did U.S. researchers between 2008 and 2012, but questions have lingered about the quality and influence of those publications. Numerous papers by Chinese researchers had zero citations, while the number of papers with over 1,000 citations by Chinese-only authors is also much smaller than that of papers co-published by Chinese researchers together with U.S. researchers. Xu Chenggang, the director of CAII, blamed the incentive mechanism within the Chinese academic system: Many researchers are evaluated by the quantity of papers they publish, not the quality.

Going deeper, Xu identified the state-run system in AI development as the root cause, especially in basic research and the development of core AI components such as high-performance integrated circuits (or chips) for machine learning. A state-run system does not work in AI development, Xu argued. In a state-run system, the government decides how to allocate resources in all aspects. However, in a new and fast-developing field with high uncertainty such as AI, Xu argued, the resources for basic research should be determined by experts in the industry, and resource allocation should be determined by venture capital. The government should step back and let the market play its role, Xu said.

At the same conference, Liu Yadong, editor-in-chief of the Science and Technology Daily, also commented that the role of the government for successful AI development should not be leadership, but guidance. Specifically, Liu said, the government should not focus on planning, but on setting up rules within which experts and private companies can compete fairly.

Overtaking on Curves vs. Alternative Routes

Another area of ongoing debate is how China can best advance in the ranks of global AI developers. As stated in several national strategies, “indigenous” or “independent” innovation should be the driving force to improve basic research and develop AI-related core technologies, implying an innovation path less dependent on existing or future foreign technology. The emphasis on indigenous innovation first appeared in 2006-2020 National Medium- and Long-Term Plan for Science and Technology Development (MLP) and later in the National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy. For AI development particularly, the 2017 AIDP further emphasized the goal of pursuing indigenous innovation in AI technology.

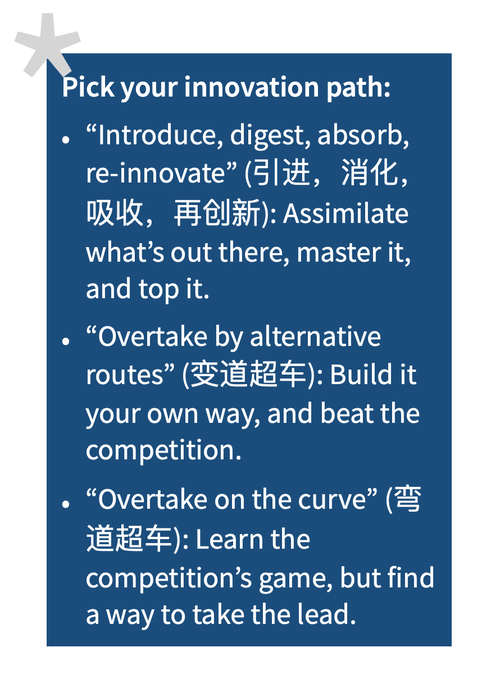

Several visions for how to achieve indigenous innovation have emerged. More than a decade ago, the MLP explained how indigenous innovation combines original R&D with “integrated innovation” and “re-innovation”*—by absorbing, reassembling, and upgrading imported technologies in new ways to produce original breakthroughs.

Since the MLP came out in 2006, however, China’s approach to innovation has evolved. China’s development of high-performance chips, for example, exemplifies indigenous innovation in practice, but also attempts more original innovation through a bottom-up approach and finding new ways to make breakthroughs. The common metaphor for this bottom-up approach is “overtaking via alternative routes.”* Chinese technology experts such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma applaud “overtaking via alternative routes” as a road to true success.

Sun Ninghui, director of the Institute of Computing Technology (ICT) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), discussing China’s chip development in a 2016 interview, explained three parallel but complementary development strategies, all promoted by the government and industry experts: re-innovation based on assimilation, absorption, and upgrade of imported technologies; innovation through overtaking on curves; and innovation through overtaking via alternative routes.

To the familiar “re-innovation” and “alternative routes” tactics, Sun added “overtaking on curves,”* which refers to catching up with foreign advances and looking for opportunities to pull ahead along the same technological track. This contrasts with an overtaking via alternative routes approach, in which one does not compete with adversaries in the same track but develops one’s own independent technology. To illustrate, Sun gave the example of Cambricon Technologies, a start-up manufacturing AI processors with investment from the CAS’s ICT and the e-commerce giant Alibaba. In 2016, Cambricon released China’s first AI Chip, Cambricon-1A, which it claimed was the world’s first commercialized neural network processor chip. Cambricon chips appear in smartphone chipsets produced by major Chinese manufacturers. “Cambricon avoided competing with Qualcomm and Microsoft in the current market, but was able to take the lead in AI field,” Sun said. They took an “alternative route.”

Because companies like Cambricon that can make breakthroughs in high-performance chip R&D field are very few, however, the other two development strategies are also viewed as necessary. Whereas “alternative route” innovation is bottom-up, both “overtaking on curves” and “re-innovation” are top-down, state-backed incremental innovation models.

The development of the Loongson CPU chip, which based its design on the non-mainstream MIPS architecture by a U.S. fabless semiconductor design company (i.e. one that designs but does not build chips), exemplifies “overtaking on curves,” whereas Sugon’s joint venture deal with U.S. chip developer AMD exemplifies the “re-innovation” approach.

While many AI industry leaders push to innovate through the bottom-up strategy of overtaking via alternative routes, China’s core of indigenous innovation remains centered around an advanced imitation strategy officially summarized as “introduce, digest, absorb, re-innovate.” This old thinking, reflecting definitions from the 2006 MLP, was evident in one of the requirements for the prestigious AI science and technology award named for AI pioneer Wu Wenjun. The Enterprise Technology Engineering Innovation Program Award in 2018 called on applicants to “master core technologies and independent intellectual property rights and solve the key, common, and supporting technology problem for industry development through original innovation, integrated innovation, and introducing, digesting, absorbing, and re-innovation.”

These debates over the best approach to advancement in AI-related industries reveal considerable dynamism below the surface of top-level goals and the consensus around which challenges China faces. Incentives may be mixed. If government awards value “re-innovation” while some experts favor “alternative route” development, a researcher could reasonably believe a bottom-up approach is most likely to work but still opt for the top-down path to be politically safe. Even more difficult, a shift to market-driven resource allocation would entail a break-up of the state-run system that is highly unlikely under current political conditions.