Sustaining Affordable Rents and Homeownership: Insights from Building Owners in Chicago’s Pilsen Neighborhood

Brief

Eddie J. Rodriquez via Shutterstock

Oct. 31, 2025

Introduction

This past summer, New America Chicago’s CivicSpace initiative and the Future of Land and Housing program at New America conducted research with residents from communities impacted by gentrification in and around the Pilsen neighborhood, to help inform The Chicago Community Trust’s Stay in Place strategy.

With rising property taxes, deferred home maintenance, and the risk of displacement from the rising tide of institutional investors, many homeowners—particularly in communities of color—are struggling to stay in their homes. This challenge is especially acute for owners who live in their two- to four-unit buildings, which represent one of Chicago’s best sources of Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH). If Chicago hopes to close the racial and ethnic homeownership gap and achieve meaningful progress to build intergenerational wealth for low-income communities, it must focus on preserving ownership and strengthening the value of homes owned by families of color.

Pilsen has a rich cultural history in Chicago as home to different waves of immigrant communities throughout the years. Irish, German, Czech, Polish, and Italian immigrants have all called Pilsen home, with Mexican immigrants becoming the majority in the second half of the twentieth century. Today, Pilsen, part of the “Lower West Side,” has a population of over 33,000 residents according to Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) data. Of these, the majority (roughly 68 percent) identify as Latino/a/e, followed by 22 percent identifying as white residents. A third of the population is foreign-born, and 60 percent of households are Spanish-speaking.

Directly related to the Stay in Place session, just over one-third of occupied housing units are owner-occupied, with nearly 55 percent of housing being two- to four-unit buildings. Housing stock in Pilsen is relatively old compared to other Chicago neighborhoods. The median year built for housing is 1933, and nearly 60 percent of homes were built before 1940. In the last decade, Pilsen has seen the largest increase in median household income of any other neighborhood in the city, with more white residents moving in and Latine residents moving out. It is a neighborhood central to the discussion of gentrification, where those working in the housing space are exploring how to help long-time renters and homeowners stay in place.

Note: Throughout this brief, quotes from Stay in Place session participants are included to highlight residents’ lived experiences and perspectives in their own words.

A companion brief on Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood and the unique challenges aging homeowners of color face to “stay in place” is available here.

Session Insights and Learnings

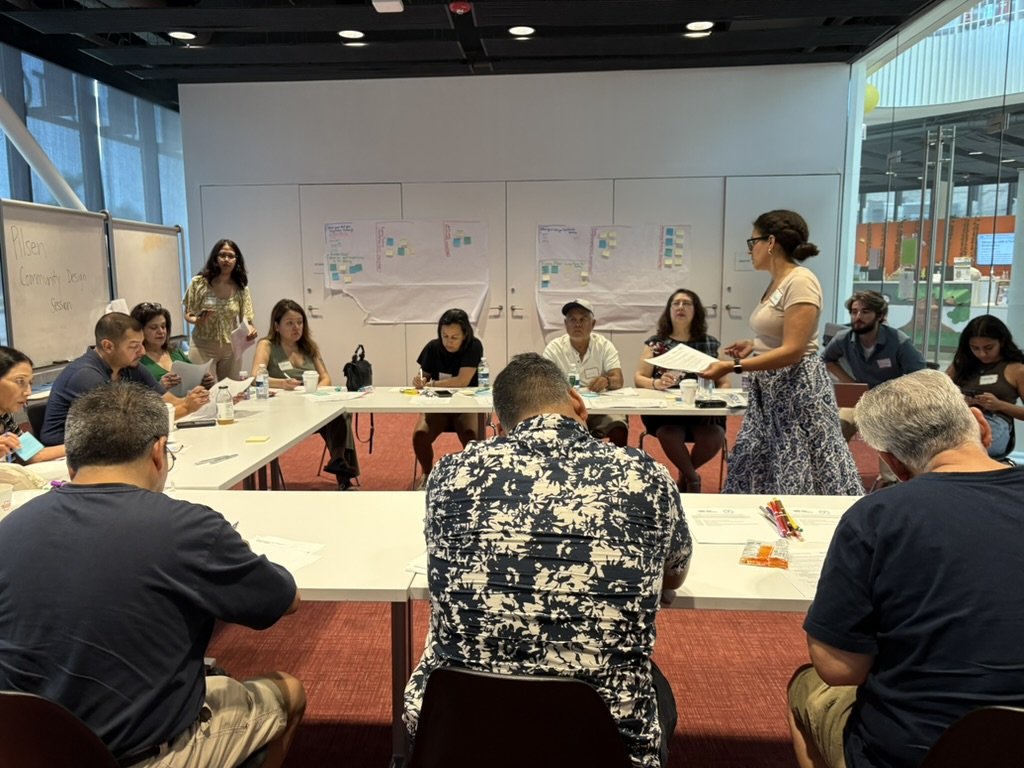

CivicSpace community design session participants share experiences with Vanessa Rangel from New America Chicago.

Source: Meegan Dugan Adell/New America

The Pilsen Stay in Place session consisted of Latino/a two- to four-unit building owners, with the goal being to better understand their challenges and the kind of assistance needed to keep and maintain their buildings.

The session explored the following research questions:

- What are the biggest barriers for building owners (of two- to four-unit buildings) in and around Pilsen to keep their building habitable and their tenants in place?

- What has made owners raise rent in the past? What are they concerned about that could require them to raise rent? What is the breaking point that would cause them to raise rent? What incentives would they need to keep from raising rent?

- What trade-offs would multi-unit building owners be willing to make for more readily accessible and flexible repair funding, such as forgivable loans, so that tenants could remain in place over the long term?

- What other factors are building owners considering when thinking about covering the costs of repairs?

- How can the factors important to building owners help design interventions and innovative products to help keep renters in place as homes are repaired and prices rise?

Below is a summary of key insights.

The Costs and Challenges of Maintaining a Building

All participants expressed a strong desire to hold onto their buildings for the foreseeable future and either pass them down to family, or, if forced to sell, to sell to long-term, reliable tenants or other families within the Pilsen neighborhood. As one owner shared, “A building is like a part of the family.” Another said, “I’m a long-term owner. I plan to eventually pay off the properties and have my sons inherit them and continue to live in Pilsen.”

Despite this deep attachment and long-term vision for community investment, participants shared several external pressures that could force them to unwillingly sell. These include:

- The cost of building maintenance and upkeep: All of the participants discussed needing to make renovations to their buildings. The catalyst for renovations, in addition to upkeep and maintenance, includes the pressure to add amenities in order to compete with developers and keep up with changing codes, such as the transition from gas to electric.

- The rising cost of living, including rising insurance rates and property taxes: This is especially difficult for those on a fixed income. The challenges here are compounded by the fact that two- to four-unit owners are not eligible for subsidies or assistance programs that would ease this burden. Participants frequently mentioned rising taxes and fees, including property taxes, insurance, and utility costs.

- The time and cost involved in the permitting process: This often delays needed repairs and adds a difficult step to the process of finding contractors and building materials.

Factors in Deciding Rent

While most participants have kept rent well below the market rate in Chicago (with 60 percent of two bedrooms under $1,300), most participants have had to consider raising rent in the last few years due to rising costs. Participants mentioned a number of shared factors in how they calculate rent for their tenants; however, nearly all (10 in 12) had given people breaks on rent in the past when they needed help. This section contains the participants’ considerations for raising rent or keeping it the same.

- All participants were torn between making enough to pay the bills versus making a profit. Several people emphasized that they were barely making enough to cover the rising property taxes, insurance, and needed repairs, and acknowledged the fact that it is difficult to make a profit themselves without overextending their tenants: “[As a landlord,] my goal is not to overcharge my tenants. I just want something stable.”

- Seven out of 12 participants had family living in their two- to four-unit buildings. Although not explicitly stated, it could serve as additional motivation to keep rents affordable.

- Half of the participants agreed that the market rate was the most important reference point for determining rent. However, three participants mentioned they used market rates for new tenants but are more lenient with existing, quality tenants.

- The duration of tenancy also played a role in deciding rent costs, as most participants agreed that they tried to avoid drastically raising rent for long-time tenants, and also took into account tenants’ own contributions to the property, and whether they paid for utilities.

Aging Buildings Need Repairs

There was unanimous agreement that all buildings were in need of repairs. The reasons for repair ranged from long-term plans for major renovations, urgent repairs due to the age of the buildings, and updates as a result of changing codes, such as costly electrical upgrades. When asked to label their maintenance needs as “must do” versus “wish list,” these patterns emerged from the group activity:

- Exterior structures were most commonly referenced in must-do repairs, including porches, stairs, fences, and gates, with the total estimated cost of needed repairs adding up to $413,800 among the building owners who knew the price of needed repairs.

- In participants’ wish list of repairs, interior upgrades were most commonly referenced. This included bathroom and kitchen remodels, repainting, green tech improvements, and creating new units, totaling $437,600 among the building owners who knew the price of needed repairs.

As one building owner told us, “We’re competing with developers, with all the new condos…and new apartments going up in Pilsen. They have the state-of-the-art, the nicest finishes, everything. In order for us to compete with that, we have to try to keep up with them.”

Building Owners Need Assistance Programs Too

Participants pointed out that there was both a lack of affordable loans and assistance programs, as well as confusion over which programs were available to participants and what the eligibility requirements included. Despite what people may assume about their financial situation due to owning a building, many felt like they were struggling to get by and needed additional support. Below are both situational and emotional barriers that arose from the discussion:

- Lack of awareness and unclear messaging: Limited awareness of available programs was a recurring theme among participant conversations. And at times, there were conflicting opinions on which programs were available, showing that the messaging around assistance programs is vague or confusing and requires bigger awareness campaigns.

- Income-based eligibility gaps: Some people mentioned being trapped between lacking the income for repairs, but not having a low enough income to access nonprofit programs. As one participant shared, “It’s not like I have a bunch of money. I have $200,000 in student loans. So I don’t qualify for a lot of these programs. But I’ve tried.”

- Unpredictable access: Participants described difficulty in getting accepted for city and nonprofit assistance programs, including the City of Chicago Pavement Repair Program, or being ineligible for assistance programs due to the type of building.

- Reluctance to take on loans: This came up frequently, with participants citing high interest rates and a fear of taking on additional loans while paying off previous repair loans.

Forgivable Loan Design Preferences

The session included a loan design activity designed to gather insights about participants’ loan preferences, and specifically the trade-offs they would be willing to accept for differing loan amounts and repayment terms.

Participants were enthusiastic about the prospect of forgivable loans, especially given the lack of affordable lending options. One participant shared, “No interest? Sign me up.” Most, if not all, of the participants were willing to make certain concessions in keeping rent low or not selling to developers for a period of time, depending on the size of the loan.

There was broad agreement that the loan terms should be flexible and clear, as some were wary of unknown future constraints and wanted to know what “affordable rent” meant concretely. Some of the takeaways from the activity and conversation include:

- Most people preferred the largest loan size ($50k to $75k) to make all or most of the repairs they needed. They also figured it would be more worthwhile to agree to keep their rent within a certain range or not sell the property over an extended period for a larger forgivable loan.

- Most said they would not pursue a loan if it couldn’t cover a meaningful portion of their big-ticket repairs (e.g., roof repair or replacement).

- Participants expressed a desire for keeping some funds as reserves or in a fund that they can draw on as needed, especially if unable to raise the rent.

- Many would accept conditions like maintaining rents at or below market (especially for existing tenants) and keeping the property for 5+ years, since they felt they were already abiding by those terms, so they might as well leverage that to get loans to be able to make repairs. However, some wanted flexibility for emergencies or family changes.

Recommendations for Funders and Housing Advocates

With the community members’ lived experience in mind, we compiled several policy and program recommendations for nonprofit partners in the housing space, funders, and other stakeholders to pursue in their work to keep multi-unit buildings affordable for both renters and owners over time.

- Increase awareness and guidance of resources and assistance programs.

- Simply getting information to people via resources and in-person workshops from trusted sources like Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation, the University of Chicago, Chicago Bungalow Association, CEDA, Neighborhood Housing Services, the City of Chicago, and Mi Hogar among others can help with keeping people in place. (Next stage: Foundations invest in these programs to expand reach.)

- Foundations investing in programs that help address specific challenges families could face in getting the most value out of the home they inherit.

- Strengthen networks of mutual help and nonprofit support in gentrifying communities.

- Fund more capacity for repair programs and expand to two- to four-unit building owners.

- Improve access to reliable and reputable contractors by vetting resources like Angi, collaborating with Habitat for Humanity, and building out training programs with the Inter-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN), community colleges, and Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act (WIOA) programs.

- Increase the availability of forgivable and affordable loans. Expanding forgivable loan programs for very low-income or fixed-income owners through a larger, low-interest revolving loan fund would help owners maintain their homes and keep renters in place. Nonprofit organizations with proper funding and Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), such as credit unions, should also test out a line of credit option for two- to four-unit building owners who live in their buildings, for any emergency that makes it difficult to keep their tenants in place.

- Pair program support with advocating for policy change to maximize impact.

- Push for improved access to city repair support programs for two- to four-unit building owners who live in their property.

- Advocate for faster and cheaper permitting for smaller owners.

- Work towards reduced property taxes for long-time and lower-income owners, including “grandfathering in” property tax rates for long-time residents.

- Support phased-in code changes or provide assistance programs to allow long-time owners to afford changes.

- Work towards a reporting system using 311 or smartphones so the city can collect helpful information about the specific challenges long-time homeowners encounter with city code or requirements. Provide a longer grace period with a payment plan to keep families in place.

- Pass limits on teardowns of affordable housing stock.

- Research and address exorbitant insurance hikes at the state level or provide alternatives for long-time owners who cannot afford the new rates.

Community members participate in a design session activity with Meegan Dugan Adell and Vanessa Rangel from New America Chicago.

Source: Emma Fenstermaker/New America

Background

Recruitment

To reach a variety of community members we embraced different methods of outreach. With Pilsen, we utilized advertising with CCT nonprofit partners, like The Resurrection Project; online forums for landlords; local newspapers; Craigslist, social media, and the NextDoor app; and local churches and the library system. There were difficulties trying to reach two- to four-unit building owners, so the criteria were expanded to include another community dealing with gentrification, Logan Square. However, flyering in the Pilsen neighborhood proved to be the most successful method for reaching participants, so we were able to fill the group with mostly all Pilsen residents except for one person from Logan Square.

For both Stay in Place sessions, we had potential participants fill out an intake form answering demographic questions as well as questions about their current living situation and future plans. From there, we followed up with those who seemed to qualify over the phone to build rapport and get to know them better to make sure the session was a good fit for their time. All of those who participated were gifted a prepaid Visa card for their expertise and valuable contribution to the project.

Methodology

Each session was facilitated by a New America staff member. A lead facilitator introduced the team and the purpose of the session, shared how the findings would be used, and offered an opportunity for participants to ask any questions. Each participant was also asked for their consent to record the interview and was provided assurances that everything shared would remain confidential and nothing would be attributed to them by name or any other identifying information. The activities that followed provided multiple ways for residents to participate in a way they could feel comfortable, both verbally in the group and in writing. Sessions were recorded, notes were transcribed, and each session transcript was cleaned for accuracy.

Participant Demographics

The Pilsen session had 12 attendees altogether—all Latino/a multi-unit building owners from areas impacted by gentrification in zip codes 60608, 60609, and 60647. The totals for the Pilsen group do not reflect all 12 participants because one person showed up last-minute as a referral from The Resurrection Project.