Fixing the finances, not the structure, of student loan servicing [UPDATED]

Blog Post

Shutterstock

Sept. 4, 2014

It pays to keep borrowers current and happy. That’s the clearest message sent by the U.S. Department of Education in the new contract terms it unveiled last week for its student loan servicing companies.

The new conditions definitely don’t signal a significant rewrite or reconfiguration of who can service federal student loans. But they do improve on prior terms in a few key ways. These changes went into effect on September 1, 2014 for the four main servicers--Navient (née Sallie Mae), Nelnet, the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA), and Great Lakes. The seven remaining nonprofit companies will shift to these terms in October.

Steeper Cuts for Delinquency

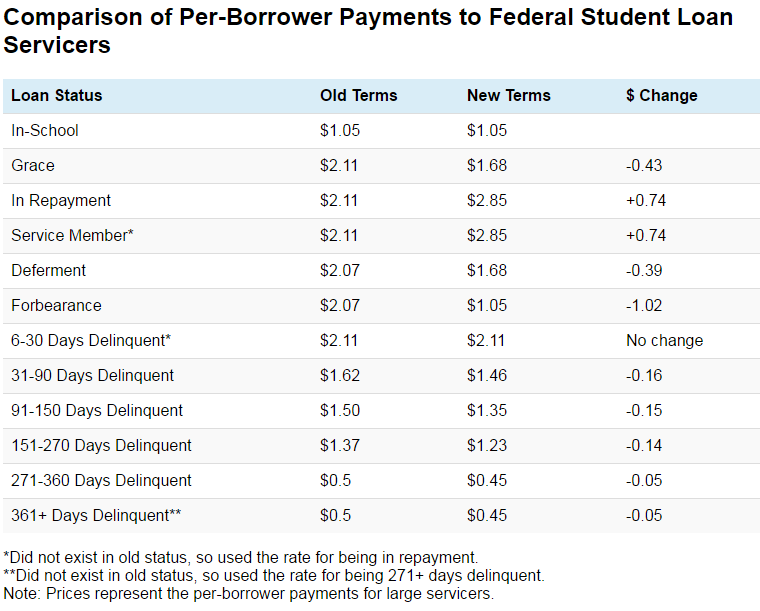

The most noteworthy change in the new contracts is how quickly they will reduce the payments to servicers as soon as a loan goes six days delinquent. As the graph below shows, a loan that is between 6 and 30 days delinquent now results in a $0.74 reduction compared to what servicers receive for loans that are current. Once a loan goes 31 days delinquent, the rate drops to $1.39 less than the current payment. And by the time a loan has gone seriously delinquent, the loss to the servicer can be as much as $2.40.

(UPDATE DEC. 2014: The prices here reflect payments to loan servicers for borrowers below beyond the first 3 million in repayment)

That's a much steeper dropoff than the older contract terms. Under those conditions, a loan that was 6 to 30 days delinquent received the same payment as one that was current, while a loan that was 31 to 90 days delinquent lost just 49 cents. Even a loan that was 151 to 270 days delinquent still represented a loss of just 61 cents under the old terms. Note: this analysis is based off of the price given to servicers for having less than 3 million borrowers and under 1.6 million borrowers in deferment or forbearance. (See the bottom of this post for a table that shows the payment terms under the two contracts.UPDATE 12/11/14: This table has been corrected to show the pricing based upon having fewer than 3 million borrower accounts since no servicer was over that threshold.

This quicker payment decrease is an important change, since the financial value of keeping borrowers current is much greater. In fact, a current loan is now worth $2.85, which is 35 percent more than the previous payment level of $2.11. It's possible that this greater payment level could also assist with enrollment in income-based repayment plans, since the additional money now paid for current loans could outweigh the costs of getting someone to complete the paperwork for these programs.

Two other positive changes stand out. First, the Department dramatically dropped the per-borrower payment for loans in forbearance from $2.07 to $1.05. That matters because the previous contract paid servicers only 4 cents less for a loan in forbearance than one that was current, making it an attractive way to deal with delinquent accounts. Now, forbearance is worth $1.06 less than a current loan. Second, the Department created a new compensation category for servicemembers. This should presumably encourage servicers to treat them better. UPDATE: this paragraph has been changed to reflect the compensation terms based upon fewer borrower accounts.

The biggest problem with the Department's changes is its monolithic treatment of deferment. Loans in this status will receive $1.68--the same as one still in its grace period. But a loan may end up in this status for very different reasons. For example, if a borrower goes back to school is there a reason why the loan should be paid at a higher rate than the $1.05 given when a loan is in school? Or what about a hardship deferment, which the servicer has greater flexibility to award? If the Department is concerned about paying less for forbearance, then why not treat hardship deferments in the same way? Some price differentiation that dropped the payment rate for in-school and hardship deferments to the same $1.05 rate given for loans in school or in forbearance would have been a welcome change.

Reweighted allocations

The Department’s changes also tweak how the four servicers will receive new loan allocations. This process used to rely upon five measures, each weighted equally. And it was done only once a year. Now, the Department is proposing to change some of the weights, replace some of the measures, and allocate new volume twice a year. The table below shows the difference between the old and new allocations metrics.

The borrower survey will now serve as the most important measure under this formula, while the school opinion has been eliminated entirely and the opinions of personnel from the Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) reduced. Both the borrower and FSA surveys are independently administered and are done through a methodology consistent with what a number of other industries use to measure customer satisfaction. This process also generates separate scores based upon the borrower's loan status. Increasing the weight of borrower opinion should establish a more direct feedback loop between borrower happiness and additional servicer business.

Arguably more important are the additions of indicators measuring the percentage of borrowers who are current, as well as those who are very delinquent but not defaulted. Adding these factors means servicers will have to care about more than just getting borrowers to avoid default. Much as the current conversation around loan performance should consider repayment and not just the absolute worst outcome, this is a welcome change. Finally, dropping any measures denominated in dollars is a good change, since students who are more likely to struggle with repayment may actually have lesser debt levels due to things like dropping out early on in a program.

Sufficiently ambitious bonuses?

The oddest addition to the contracts is a new “delinquency reduction compensation program.” This allows servicers to earn up to $500,000 every quarter (and $2 million total) based upon the percentage of their borrowers in current or delinquent repayment status that are more than 30 days delinquent. Servicers hoping to receive any bonus have to keep the percentage of those loans that are more than 30 days delinquent below 23 percent. Those who can keep the rate below 21 percent and improve upon the prior’s quarter’s results can get the maximum $500,000 bonus.And servicers can keep earning this money each year.

The idea of bonuses isn't crazy, but the targets chosen appear to be unambitious reflections of the status quo. For example, 23 percent of direct loan borrowers in repayment that were more than 30 days delinquent at the end of the third quarter of 2014—the exact threshold servicers have to meet in order to receive a $200,000 bonus. Essentially treading water would thus allow servicers to still pocket a lot of money, while a small reduction could be quite lucrative. The table below shows the different requirements needed to earn bonuses.

What’s Missing?

Except for the bonus payments, the financing and allocation changes are sensible alterations that should better align servicers’ financial incentives with the outcomes we want to see for borrowers. Unfortunately, what they will not do is address larger structural challenges in the program. On the smaller side, this means borrowers still will not be able to choose or switch servicers as needed, something they can do if they go through the new consolidation process. And servicers are still allowed to use their own interface and branding on websites, meaning borrowers will not have a standardized loan portal and could get confused.

There are larger issues too. Apart from loss of future volume, there appear to be no new clearly outlined penalties or consequences for servicers that may do a poor job or that violate things like the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. The Department's announcement also signals it will award new borrower accounts to nonprofit entities that got into the program thanks to Congressional pork. The Department is not required to do this under law and hopefully it will not give additional accounts to some of those servicers that look pretty bad.

The broadest issue, though, is not about about contract terms and conditions. It's behavioral. For these changes to be maximally effective, they must come with a change in the way the Department oversees and works with these servicers that places a greater demand on high-quality results. Relying only on dollars to send that message will not be enough. Increased scrutiny and accountability must be a part of any new deal.

The table below shows a full comparison of different payment amounts.