Foreign Assistance and Fragile Situations

Blog Post

Nicolas Economou / Shutterstock.com

March 16, 2020

In 2018, 17.5 million refugees around the world originated from fragile and conflict affected situations; a 144 percent increase since 2000. That’s more people than the entire population of Finland, Singapore, and Denmark combined.

But what exactly makes a situation “fragile”? Definitions vary.

The United Kingdom’s Department of International Development describes a country's situation as fragile if the “government cannot or will not deliver core functions to the majority of its people, including the poor.” The American counterpart, USAID, on the other hand, defines fragile states as having governments that are “unable or unwilling to adequately assure the provision of security and basic services to a significant portion of their populations and where the legitimacy of the governments is in question.” The International Monetary Fund differs in that it lists a range of characteristics, such as “weak governance, limited administrative capacity, chronic humanitarian crises, persistent social tensions, and often, violence or the legacy of armed conflict and civil war.” In other words, fragile states can be defined in any number of ways, but it’s basically unsafe living conditions at a systemic level for a large number of people.

A recent bill tucked into the 2020 Consolidated Appropriations Act combines some of those definitions and clarifies what “fragility” means to the United States. It also sets criteria for the application of foreign assistance funds to priority countries or regions, based not only on fragility, as measured by fragility indices, conflict watch lists, as well as vulnerabilities to various climate-related disasters, but also importance to U.S. security and capacity to work with donor institutions.

The Global Fragility Act (GFA) spells out a holistic approach for focusing U.S. foreign assistance on fragile countries. All conflicts are different, with multiple, complex, and sometimes interrelated causes. To zero in on on conflict prevention, as opposed to containing existing conflicts, the GFA authorizes three funding streams annually from 2020 through 2024: the Multi-Donor Global Fragility Fund (public and private sector contributions), the Prevention and Stabilization Fund ($200 million/yr), and the Complex Crisis Fund ($30 million/yr). Overall, the GFA dedicates $1.15 billion over the next five years to address the root causes of conflict.

In addition to funding, the legislation also lays out a timeline for keeping the executive branch accountable. For example, 270 days after the enactment of the GFA, the President must submit to Congress a detailed Global Fragility Strategy. Further, one year after enactment, the President and relevant federal agencies must submit a 10-year strategy for preventing conflict in priority countries and regions. This 10-year strategy is to “align and integrate … relevant diplomatic, development, and security assistance …” provided to each country and region by the United States. Within two years of enactment, the President must provide to Congress a biennial report on the implementation status of the GFA.

Agencies in lead of implementing this legislation include the Department of State, USAID, the Department of Defense, as well as other relevant federal agencies. But the government agencies are not the only actors involved. The GFA mandates that, in developing the Global Fragility Strategy, the government consults with development organizations, subject matter experts, and other relevant civil society actors with expertise in fragile states.

We identify a few priority countries by comparing country rankings from the Fragile States Index (FSI), Global Adaptation Initiative Index (NDGAIN), Natural Security Index (NSI), and Corruption Perception Index (CPI).

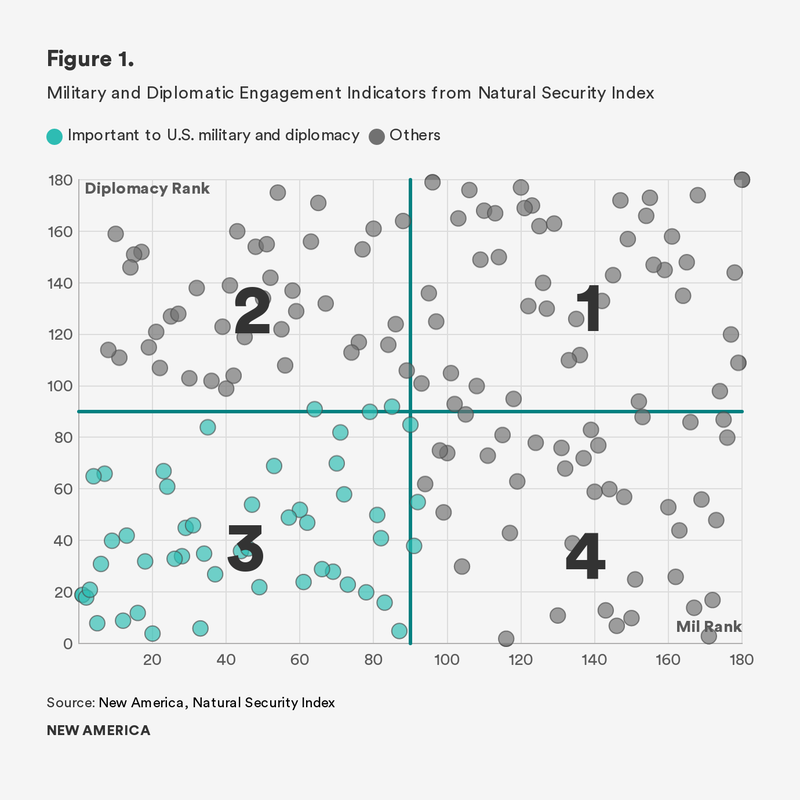

First, we looked at the military and diplomatic engagement indicators on the NSI, and created a scatter plot with quadrants to identify the countries that are important to U.S. national security (Fig. 1).

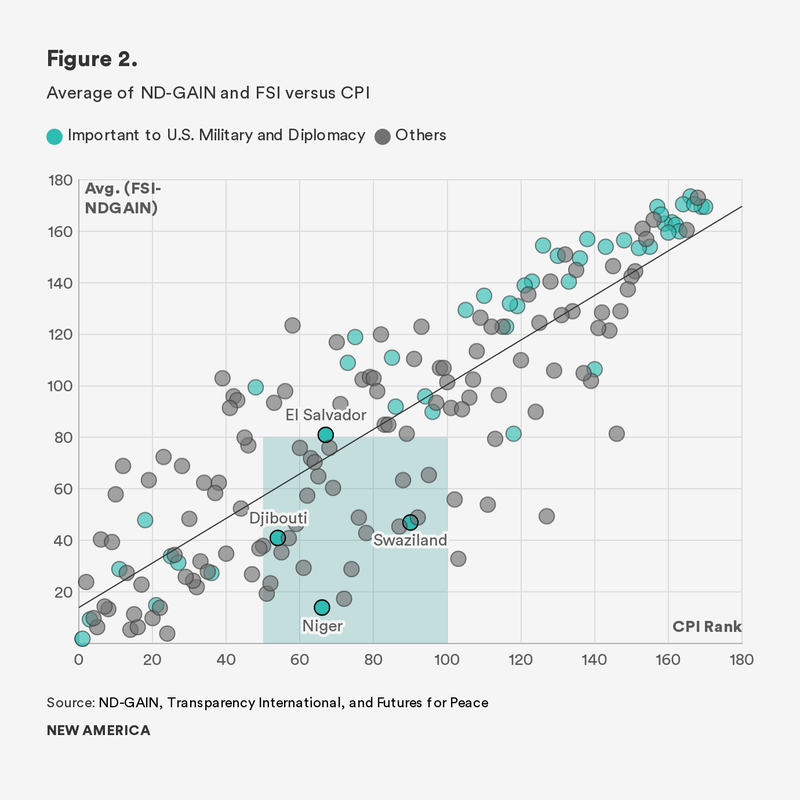

After identifying priority countries using the NSI, we then average country rankings from the FSI and ND-GAIN, and plot this average on a scatter plot with CPI ranks (Fig. 2). In Fig. 2, the shaded area represents countries that rank high-to-moderate on FSI and ND-GAIN (e.g. highly/moderately fragile and highly/moderately at risk to climate change), but rank moderate on the CPI. The reason for shading and selecting in this way is because the criteria for selecting priority countries set forth in the legislation requires examining state capacity to administer funds and work with donor institutions. Thus, while Afghanistan and Somalia are highly vulnerable to climate change and among the most fragile states, when it comes to corruption and state capacity, it may make more sense to focus GFA funds on countries that are less corrupt.

U.S. officials may want to consider these data when prioritizing countries and regions for the Global Fragility Strategy. By prioritizing in terms of military and diplomatic engagement indicators, then analyzing the average country ranks on the ND-GAIN and FSI indices, and comparing that rank with those of the CPI, we get a better idea of which states are of importance to U.S. national security and may be more transparent and accountable if they were to receive GFA funds. El Salvador, Djibouti, Swaziland, and Niger all fit this profile.

The GFA is a welcome step in the right direction for strategically using the United States’ vast array of foreign assistance tools. Before becoming law, the bill had bipartisan cosponsorship in both chambers of Congress, signaling agreement on the need to rethink the way the United States approaches foreign aid. Leveraging foreign assistance resources in a proactive manner to maximize impact can prevent fragile situations from developing into situations ripe for violent extremism and instability. With a long-term plan like the Global Fragility Strategy, the United States can apply its foreign assistance capabilities—diplomacy, defense, and development—in a coherent manner to address the fundamental, underlying causes of conflict.