Labeled

The Students Behind NCLB's "Disabilities" Designation

Blog Post

July 12, 2007

It's not hard to find news reports about the federal No Child Left Behind Act claiming that the law is requiring teachers to give standardized tests to severely disabled students.1 These stories frequently portray all special education students as having the same severe disabilities and bolster calls for changes to NCLB's accountability provisions for special education students. But the majority of special education students are not severely handicapped. With special services and accommodations, they are able to perform at grade level.

As part of its accountability requirements, NCLB calls for schools to separate test-score data by student subgroup—categories of students that include major racial groups, low-income students, English language learners, and students with disabilities. This prevents schools, school districts, or states from letting high overall student achievement hide low achievement among certain groups of students. NCLB defines the students-with-disabilities subgroup as all students served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). As Chart 1 shows, this is a broad definition and includes students with a wide range of disabilities.

Nearly half of the students served under IDEA are classified as having "specific learning disabilities." This classification, often referred to as "learning disabled," or LD, is vaguely defined under IDEA as "an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations," and it is often described as a discrepancy between a student's intelligence level and his or her performance in the classroom.2

The LD diagnosis is intended to provide students with the supports they need to reach grade-level standards. Similarly, students with disabilities that fall into the categories of "emotional disturbance," "speech or language impairments," and "other health impairments" (which includes attention deficit disorder or ADD) can be expected to overcome or compensate for the disability with appropriate services.3 Over 80 percent of students enrolled in special education fall into these four categories.

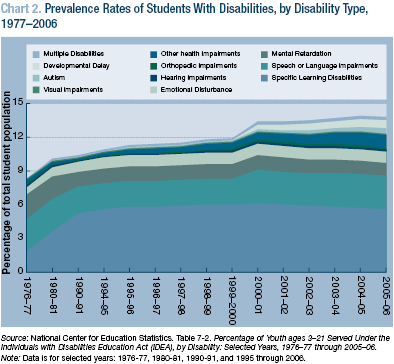

These categories also are among those with the largest increases in student diagnoses over the years. Chart 2 shows the rise in students with disabilities as a proportion of the total student population and the change in the prevalence of disability types.

Overall, the percent of students with disabilities in theUnited States has grown from just over 8 percent of the total student population in 1977 to nearly 14 percent in 2006. But this increase has not been uniform across all disability types. The biggest increases have been in the "specific learning disabilities" category, which grew over 200 percent during this time; the "other health-impairments" category, which began to increase in 1991 when the federal definition was expanded to include ADD and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); and in autism, which has increased partly due to an expanded definition that includes children with milder forms of the disorder.4

The increase in students identified as having disabilities is a reflection of a variety of factors, including an increased acceptance of the "disabled" label among parents and students, a better understanding of disabilities, and changes in the definition of what qualifies as a disability.

But some researchers have argued that the increased prevalence of students with disabilities, particularly in the broad "specific learning disabilities" category is also a result of over-identification. Here, schools may improperly identify low-performing students as learning disabled for a variety of reasons: to get additional state funding for special education, to avoid accountability for these students because the special education label has historically exempted these students from such measures, or more simply, because the vague definition of a disorder leads to misidentification or because teachers are trying to get additional help for struggling students.5 Added flexibility to NCLB's accountability for the performance of special education students could mean that many of these misidentified students will not be required to reach grade-level standards.

Over-identification is a particularly important issue because of the over-representation of minority students in a number of special education categories. Chart 3 shows the proportion of students of each disability type by racial category. The horizontal lines represent the percentage of each race in the total student population. Where a bar for a particular race exceeds that group's line, the race is over-represented in that disability category.

African American students make up approximately 15 percent of the total student population, but represent 21 percent of the special education population. This difference is even more pronounced when divided by disability type. African American students are much more likely to be diagnosed with mental retardation, emotional disturbances, or developmental delay, making up 34 percent, 29 percent, and 22 percent, respectively, of those populations. White students, on the other hand, are more likely to be diagnosed with autism, making up 68 percent of that population compared with only 62 percent of the total student population, and also with other health impairments, making up 71 percent of those students.

The over-representation of minority students in special education means that these students will be disproportionately affected by any changes to NCLB's accountability measures for this subgroup. But it also has led some to believe that minority students are more likely to be misidentified as having a disability, especially because the identification process is often highly subjective and dependent on the observations of a student’s teacher. Researchers Matthew Ladner and Christopher Hammons argue that school districts "do not make special education placements in a color-blind fashion," and that race "plays a powerful role" in whether students are placed in special education, even when controlling for other factors.6

Lawmakers, and education groups, such as the National School Boards Association and the National Education Association, have called for more flexibility in NCLB accountability provisions for special education students because the students-with-disabilities subgroup often requires the most intensive instruction and is often the lowest performing subgroup.7 And the Department of Education has responded by allowing states and districts to count, for NCLB accountability, passing scores from special education students tested with "alternate assessments," or under "modified standards."8 Approximately 30 percent of special education students can be tested this way for NCLB.

But because the majority of special education students have disabilities that do not preclude them from reaching grade-level standards there doesn't seem to be a need to rollback NCLB's accountability measures for students with disabilities. To the contrary, doing so could hurt such students by reducing schools' responsibility for ensuring that they are taught to high standards.

It would also go against the views of the many parents of special-needs children who argue against labeling their children as "perpetual underachievers," or "writing them off" academically.9 As Madeline Will, vice president of public policy for the National Down Syndrome Society, has argued, the law is "more than an accountability statute; it is the institutional embodiment of the high expectations that students with disabilities need to succeed."10

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Endnotes

1 See for example, Susan Gvozdas, "Law Doesn't Fit All, Teacher's Say," The Baltimore Sun, January 14, 2007, or Karen Gutierrez, "Disabled Tested, too," The Cincinnati Enquirer, March 5, 2006.

2 G. Reid Lyon, Jack M. Fletcher, Sally E. Shaywitz, Bennett A. Shaywitz, Joseph K. Torgesen, Frank B. Wood, Ann Schulte, and Richard Olson, "Rethinking Learning Disabilities," inRethinking Special Education for a New Century, eds. Chester Finn, Andrew Rotherham, and Charles Hokanson (Washington, D.C.: Public Policy Institute, May 2001).

3 Rewards & Roadblocks: How Special Education Students are Faring Under No Child Left Behind (New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2007).

4 Wade F. Horn and Douglas Tynan, "Time to Make Special Education 'Special' Again," inRethinking Special Education for a New Century.

5 Ibid.

6 Matthew Ladner and Christopher Hammons, "Special but Unequal: Race and Special Education," in Rethinking Special Education for a New Century.

7 See Christina A. Samuels, "Advocates for Students With Disabilities Balk at Proposed NCLB Changes," Education Week, July 6, 2007.

8 These measures include a 2003 provision that allows states to include in their count of "proficient" students the scores of students tested under alternate assessments, which are intended for students with the most severe cognitive disabilities, and a 2005 provision that allows states and districts to count as proficient the scores of students tested with "modified standards," which are intended to cover those students who do not have severe-enough disabilities to require alternate assessments, but cannot achieve grade-level standards in the typical timeframe.

9 When It's Your Child: A Report on Special Education from the Families Who Use It (New York: Public Agenda, 2002).

10 Commission on No Child Left Behind, Testimony of Madeline Will, Vice President of Public Policy, National Down Syndrome Society, September 25, 2006.

This work by Education Sector is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.

Education Sector encourages the free use, reproduction, and distribution of our ideas, perspectives, and analysis. Our Creative Commons licensing allows for the noncommercial use of all Education Sector authored or commissioned materials featured on this site. We require attribution for all use. Link to and credit Education Sector as the original publisher of the work and, if applicable, also credit a particular author.