Why We Don’t Need to Get Rid of Common Core to Have Play in Kindergarten

Blog Post

April 1, 2015

My first experience in elementary school was magical. My kindergarten teacher Mrs. Mantz was friendly and warm, and I remember meeting my first friend, Marwa, in the play area. I showed her around the kitchen pointing and telling her the names of different plastic foods as we played. Kindergarten was Marwa’s first experience in school and she was just beginning to learn English. Our time together in the play kitchen-- or what I would later learn to refer to as the dramatic play center--developed her language skills as well as my own.

Now, I enjoy observing young children read their environment and discover written words and new vocabulary through play when I have the opportunity to visit elementary schools. Like the time one of my former pre-K students, Amy, looked up from building in the block area and noticed that there was a word on our classroom door. She took her finger and pointed to each letter as she said, “D-O-O-R. Door.” What a discovery!

Literacy and reading are everywhere-- that’s the incredible thing about teaching young children to build language, listening, and reading skills. The educator-constructed classroom environment enables children to become excited about school and learning. Even when children leave school, they are engulfed by a world that is filled with words.

Teachers use learning standards to develop instructional strategies and an enriching environment to foster literacy skills. The standards are a frame to help teachers think about what students need to learn by the end of the school year. Most people have heard of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The National Governors Association and the Chief State School Officers, two bipartisan bodies, launched the work to create the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) because there was a wide range of learning goals across the states — some with lower benchmarks at different grade-levels than others. Although the Common Core was bipartisan in its inception, the discussion surrounding the standards has shifted to an often politicized and ideological debate.

In early childhood, however, the debate is not about politics-- it’s about whether the standards are developmentally appropriate. Some early childhood advocacy groups, like Defending the Early Years, question the kindergarten English Language Arts standards because of the perceived focus on reading. It’s well known that children develop reading skills at different rates and during this stage of development the range of skills can be wide among a classroom of students. Additionally, the sole focus on content standards (reading and math) is not always conducive to addressing other early childhood goals, such as developing socioemotional skills, approaches to learning (like persistence and problem-solving), and physical development.

While, the majority of states have voluntarily adopted and implemented the Common Core standards, this does not mean that every classroom is the same. Teachers must read the standards and plan their lessons to facilitate how each individual student will learn and work towards his or her goals by the end of the year. The way that school leaders interpret the reading standards largely determines the kind of learning environments teachers are able to create to support the Common Core.

These implementation concerns were raised in a 2012 policy brief from the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Under the Common Core, some kindergartners are experiencing early childhood best practices, while others are being subjected to the worst, because of misguided interpretation and implementation of certain standards. In the best kindergarten classrooms, children are working in centers and are authentically being introduced to new vocabulary, writing, and other literacy skills, often through play. However, in other classrooms, children are robotically completing worksheet assessments and circling answers to "build literacy skills." (Not appropriate for a 5 year-old.) This broad variation of Common Core implementation at the kindergarten-level is a result of misinterpretations of the standards and a lack of understanding about how young children learn, which contributes to the push-down effects that are negatively impacting kindergarten children.

The Implementation of Kindergarten Common Core Can Follow Early Childhood Best Practices

There are schools that have implemented Common Core in kindergarten classrooms using center-based play to facilitate learning in all domains of development (social and emotional, cognitive, physical, approaches to learning, literacy and language, and math). One of the more controversial standards is: “Read emergent-reader text with purpose and understanding.” Some advocates argue that this goal is unrealistic for kindergarten. Others, like the Fordham Institute, argue that teaching children to read in kindergarten is not harmful and that educators should work towards aspirational goals by challenging all kids. There is a middle ground. Dorothy Strickland, Rutgers University, says, “High-quality means that indeed we have exposure to high cognitive skills, high-quality experiences, but they are engaging and they are playful and that we don’t have to choose play as opposed to high-quality cognitive education.” It is the job of school leaders to create an environment where teachers can facilitate high-quality, child-directed learning experiences to strike this balance between these high standards and early childhood best practices.

Although this current debate over the introduction of reading instruction at the kindergarten-level is contentious, it is not new. Many parents and society at large want their children to begin reading at the end of kindergarten. When I interviewed a parent from Michigan about her expectations for her daughter who will enter kindergarten in the fall she said, “I want her to be reading fluently by the end of kindergarten. I would like her to have basic addition and subtraction skills. I would like her to develop her science and social studies skills as well. She knows all of her letter sounds and can sound out basic words, already.” But what does “reading fluently” really mean? Is it a reasonable expectation, and is that what the Common Core is asking of kindergartners?

Again, the Common Core standard is “read emergent-reader texts with purpose and understanding.” So what does “emergent-reader text” mean? Robert Pondiscio of the Fordham Institute addressed how the standards define emergent-reader texts, explaining that these books include a combination of sight words (a, the, who) and consonant-vowel-consonant words (cat, bag, peg).

As early education advocates rightly caution, developmentally, students learn to read at different times. For instance, by the end of kindergarten, some children may be able to read simple books that might contain two words per page that correspond with the pictures and may include a repetitive sight word, while others may be able to read something like Where’s Spot?. The Common Core kindergarten standards account for this range of development.

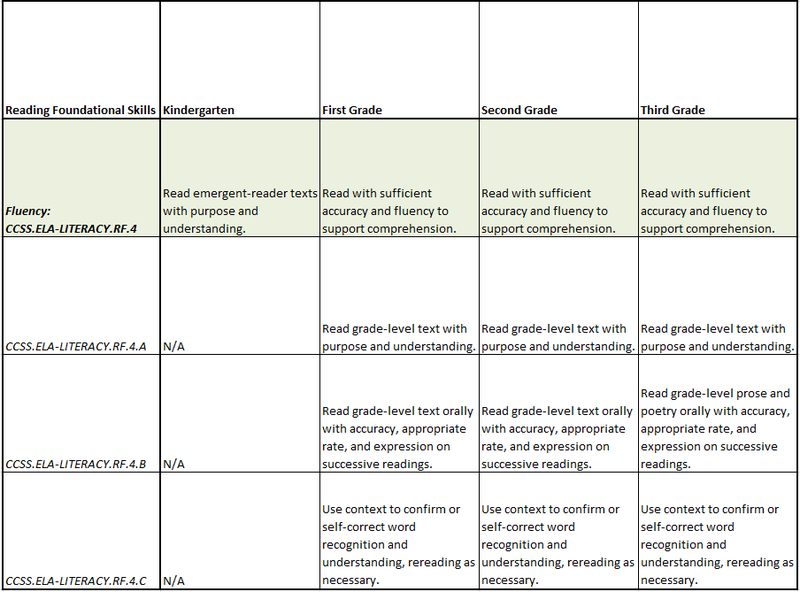

You can see in the chart below, the kindergarten Common Core Standard does not designate that students should be reading at “grade level”. This is, however, specified for students in grades first through third.

The Common Core standards are not the problem. They leave room for children’s developmental pace. The real problem is implementation. Some school systems have decided to set a kindergarten end of the year “grade-level text” reading goal that is the same for all students (despite the fact that for some children, kindergarten is their first-time in a formal learning setting) and are evaluating teachers against a goal that may not be attainable for children who have not yet developed all the enabling skills for reading. This policy encourages teachers to overfocus on the district’s grade-level reading expectation rather than on instructing in ways that kindergartners learn best.

It is important for teachers to have the flexibility to teach the emergent-reader standard in an appropriate way that individualizes learning for each child. In addition, there are many other standards that teachers need to address throughout the school year. To be sure, it is a challenge to seamlessly scaffold all of these standards in real-time, through play. But, it is even more challenging to help students meet the standards when children are only in school for three hours a day. New America’s Early Education Initiative has discussed the benefits and importance of school districts’ providing full-day kindergarten. My colleague, Laura Bornfreund, explains that the Common Core kindergarten standards were not created with half-day kindergarten in mind. Without full-day kindergarten, schools may short change children’s learning and development to achieve the reading and math expectations for which they are held accountable.

The case for more play in today’s kindergarten classroom is legitimate, and school leaders need to know that there is a way to integrate intentional play back into the classroom while teaching the high-level literacy skills that are found in the Common Core. Play is so important, particularly for young children, to develop long-term cognitive skills that will enable students to become “college and career ready”, in the long-term. Principals must be convinced that a print-rich kindergarten classroom that fosters language and literacy development is possible through play, rather than primarily through direct instruction.

To reintegrate play back into the kindergarten classroom, we don’t need to get rid of the Common Core. We need to explain to school leaders that teaching in the ways young children learn best will achieve better outcomes for children, than any “Common Core” aligned worksheet ever could.

*Student name was changed to protect her identity.