Eligible for Luck?

Weekly Article

Shutterstock

May 12, 2016

My parents, first-generation Americans, worked tirelessly to ensure I had access to everything I would need to succeed academically, professionally, and personally. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized just how exceptional my childhood really was. More often than not, people don’t make it out of the types of neighborhoods my parents grew up in, and while my parents worked very hard to get where they are, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that, for many, working tirelessly is not enough. Luck played its part in my parent’s, and, in turn, my own success. But luck should not be a, much less the, determining factor when it comes to whether a person is able to pull themselves out of poverty. We need systems that work to address short-term needs and support long-term success.

Dreaming of a more equitable, less luck-dependent world was not enough for me. I joined AmeriCorps and started working for a D.C.-based nonprofit, LIFT, where staff and volunteers partnered with community members to help them navigate the complex system of public and private resources needed to achieve economic stability. I collaborated with clients to create resumes for their employment searches, generated referrals for free or low-cost medical assistance, and helped people pull their credit reports, among other, still more varied tasks. While it was fulfilling to assist people in such a direct way, when it came to accessing affordable housing or disputing public benefits claims, I was always silently fuming over how little I could do. Red tape kept my hands tied as I explained, time and time again, “I’m sorry. There’s nothing I can do.”

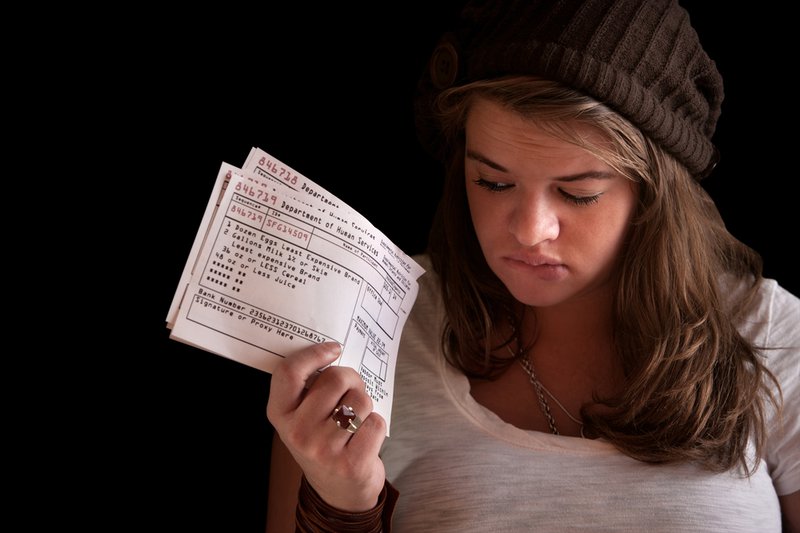

Each time a community member came in to access those benefits, there were a set of questions I asked to determine if they were eligible. If the client was above the income limit (calculated using federal poverty guidelines), they were ineligible. If they had too much money in their savings accounts, they were ineligible, although that didn’t happen very often because many clients were unbanked. Some benefits have a limit on how often or how long a person can receive them. If a person or family was over that limit, they were—you guessed it!—ineligible. Small deviations from arbitrary guidelines regularly prevented people with clear needs from receiving support.

The list of families and individuals I could not help is depressingly long, and out of all of those people, there are two individuals who stand out in my mind: Ms. Anderson and Ms. McCallister.*

After moving to the area from Pittsburgh, Ms. Anderson needed to find a new home. She had a housing voucher for a two-bedroom apartment, so Ms. Anderson and another staff member went to work looking for a place within the monetary limit listed on the voucher. We found a suitable apartment quickly and the landlord accepted Ms. Anderson’s rental application, but we then ran into a roadblock: Ms. Anderson didn’t have enough money for the security deposit. Rather than admit defeat, we turned to the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) for help. Given that Ms. Anderson was under the income limit and hadn’t received ERAP within the last year, we were confident she would receive the assistance she needed. Unfortunately, she, too, was ineligible.

Why? Because though Ms. Anderson met all of the requirements listed on the ERAP application, she was not yet a D.C. resident. Since she was temporarily staying with her uncle in nearby Maryland, she was encouraged to apply there, only to find herself turned away for the same reason. We had reached an impasse. The last time I spoke with Ms. Anderson she genuinely believed that no one—not family, friends, community organizations, the government, nor I—could help her. And so it was that a technicality prevented Ms. Anderson from accessing a service created explicitly for the purpose of helping people in situations like her own.

A similar situation prevented another member, Ms. McCallister, from accessing the services she needed to move into her new home. Ms. McCallister was retired and collecting a pension from the D.C. City Government, and while it was just enough money for her, it was not enough to support the extended family in her care. Her niece’s job had unpredictable hours, which made it hard to estimate their combined monthly income in advance. Nevertheless, they knew they needed more space. Like Ms. Anderson, she turned to ERAP for assistance. Like Ms. Anderson, she was deemed ineligible. Though her pension was barely enough to support her family, it was $100 too high for ERAP.

Throughout my time on the frontlines with LIFT, I saw families doing everything in their power to get ahead, only to be knocked down a few pegs because of bad policy. I realized that if I wanted to make lasting change, I needed to work to change the very systems that were so often failing people like Ms. Anderson and Ms. McCallister. The policies I work on now are personal to me because they seek to improve the economic stability of American households filled with people I have met. People who were ineligible for luck. People for whom luck shouldn’t have to play a part.*Names have been changed