The Hidden History of America's 'Code Girls'

Weekly Article

National Security Agency / nsa.gov

Oct. 19, 2017

As the United States moved into World War II, thousands of young women moved to Washington, D.C.

After receiving invitations to join a secret government project, these women—teachers, mathematicians, and students recruited from around the country—arrived with no knowledge of what they were there to do.

They soon learned that they were part of a government project to decypher and decrypt the Axis Powers’ communications. The United States had lagged behind other nations in its cryptology studies, but World War II forced the country to invest more heavily in codebreaking.

At a time when they were expected to stay in the home, more than 10,000 women became codebreakers. They were sworn to secrecy; if anyone asked where they worked, they were to say that they were secretaries. They became invaluable members of an effort to crack the codes of the Axis Powers, protect American troops, and, ultimately, win the war.

The stories of these brave and brilliant women are now being told in Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II, a book by Liza Mundy, a New America senior fellow and a New York Times bestselling author.

“The women are pleased, as they should be, that their story is coming to light,” Mundy said at a New America and Future Tense event on Tuesday. “They were told to keep this secret, and they did for more than 70 years. Their contribution was almost forgotten by history. And, as a result, we’re still contending with some of the myths and stereotypes about women—this idea that women aren’t biologically fit to work in the tech sector. And yet, we see from these stories that it was women who were pioneering the tech sector during the war.”

It was a woman, for instance, who cracked Japan’s Purple cipher after many others had called it undoable and had given up. It was women who studied and understood U.S. military radio traffic to such an exact degree that they were able to create fictitious radio signals—known as dummy traffic—to convince German soldiers that the D-Day invasion was going to occur in a different area of France. It was a 22-year-old woman who was selected by her peers to be the head of a cryptographic unit, which was responsible for enciphering U.S. codes.

It was women, above all, who dedicated themselves to serving their country in secret, knowing that they might never see public recognition for their work.

In addition to uncovering and celebrating the work of female codebreakers, the book also serves as inspiration for women in the tech sector today, a point that Courtney Eimerman-Wallace, director of technology at civil rights advocacy organization Color of Change, noted.

“It’s important for us to have these stories, because sometimes it feels like we’re constantly paving the way,” Eimerman-Wallace said. “For some of us in this work right now, it’s a reminder that there were people before us who got through and did amazing work, and we are the next generation. We’re standing on their shoulders, and this book allows us to continue to build on the work they did. These stories allow me to experience the people in front of me while trying to pull the young women behind me.”

Yet as brilliant as these women were, their positions were never expected to last beyond the war. As Mundy found in her research, recruiters of codebreakers knew that after the war, regressive social norms would push women out of the workplace and encourage them to be, instead, wives and mothers—the role for which society felt they were truly meant. And indeed, once the war ended, multiple measures were taken to ensure there was no place for women in the workplace, which has contributed, in no small part, to a lack of women in STEM fields today.

Although countless women dare to enter male-dominated fields, they often encounter unwelcoming, sexist environments—environments that are only worse for women of color. Eimerman-Wallace noted that even the most well-intentioned diversity programs may not be enough. Erie Meyer, senior director of the National Network at Code for America and co-founder of the U.S. Digital Service, echoed this sentiment.

“The talent we’re losing out on because of systemic sexism and racism is costing us more than we’ll ever know,” Meyer said.

Both Eimerman-Wallace and Meyer noted the importance of Mundy’s book, as well as the power it has to energize and empower women.

“When I read about these women, what strikes me is how I want to live up to that,” Meyer said. “I want to create that energy and that space for women to live up to their talent. And I can’t see a future where we make it without doing that.”

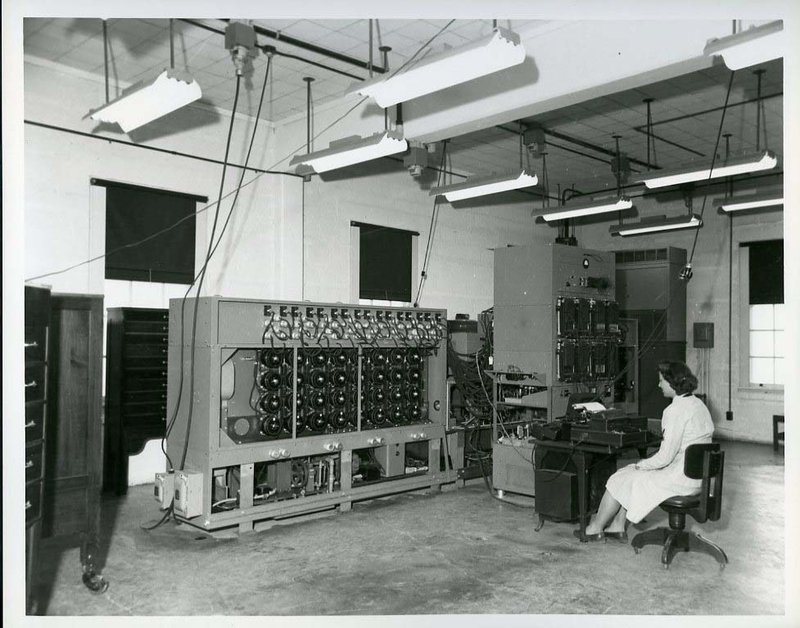

While many of these women were ushered out of their positions after the war, their work left a lasting impression; the cryptology offices and departments of World War II eventually became what we recognize today as the National Security Agency (NSA). And one of the female codebreakers from World War II, Ann Caracristi, became the first female deputy director of the NSA.

More than that, though, their legacy will inspire a new generation of women to scramble gendered notions of the kinds of work women allegedly can and can’t do—women who, like the female codebreakers of World War II, will make it possible for women behind them to push the needle of progress more than they ever imagined.