Every Community is Resilient

Learning from how communities share information every day to plan for community-based emergency communications.

Blog Post

Oct. 5, 2015

Amid talk of our tech-dependent, always-on culture, it’s hard to imagine that most people who have experienced a major disaster in this century have been cut off, unable to contact loved ones or find vital information. Yet communications “black holes” have occurred in every major disaster -- from 9/11 through Katrina, the Boston Marathon bombing, and Sandy. Volunteers resort to word-of-mouth, flyers, and bullhorns to organize aid efforts; contradictory information and rumors get passed around; and vulnerable communities like elders, people with mobility challenges, and non-English speakers may not receive or understand alerts.

Most communications preparedness efforts focus on official emergency management, and there is a good reason for this: first responders need good information so they can save lives. Yet residents on the front lines, whose households and communities are under extreme stress, also need emergency communications. People have to communicate to help their neighbors, families, and friends in need, to find out where to go for shelter, water, food, information and comfort -- in fact, community residents and local organizations are also critical responders. Viable citizens’ communications networks and strategies are essential during a disaster.

In gearing up to start work on our RISE : NYC project bringing community wireless networks to Sandy-affected neighborhoods, I had the opportunity to co-facilitate a series of resilience workshops with the Municipal Art Society in April and May of 2015. The Municipal Art Society organized the workshops with local partners in Staten Island, Queens, the Bronx, and Brooklyn, bringing together stakeholders from community-based organizations, long-term recovery organizations, and other groups to gather feedback towards a city-wide framework for support of community-based resilience building efforts.

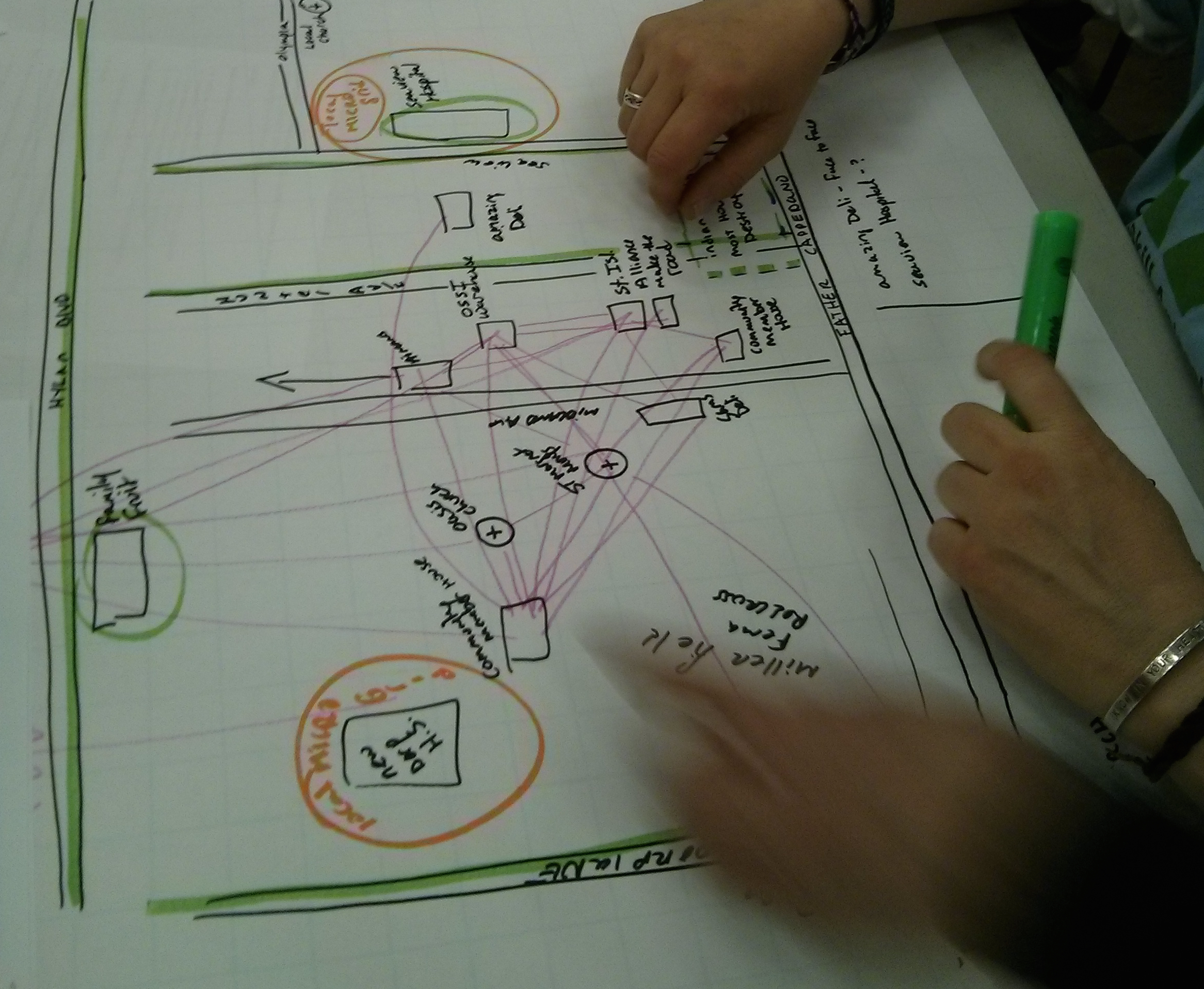

New America’s contribution to the convenings was a participatory mapping module co-developed with Detroit-based social enterprise The Work Department, a design studio that partners with businesses and organizations to increase social impact using human-centered and participatory design processes. The collaborative mapping module, “Every Community Is Resilient,” focuses on understanding local communications needs. It uses a participatory planning approach to share knowledge about communication assets and patterns in a neighborhood (e.g., where do people go for information, who do they listen to, which kinds of media do they use and trust). The workshop was intended to help residents, and the organizations and agencies that support them, plan ahead for communications resilience.

Participants discuss a local communication hub at the Municipal Art Society’s Staten Island community-based resilience convening.

Two and a half years out from Sandy, a series of initiatives and efforts have been implemented in the storm-damaged areas where we held the workshops. Yet many people have not been able to return home, and many more have spent retirement or personal savings to rebuild. With sea level rise and flood risk on the horizon, a focus on resilience and preparedness for the future is urgent for these neighborhoods. Yet residents are also suffering from “recovery fatigue” -- they’ve gone through extensive and repetitive aid processes with different agencies, efforts, and initiatives, for the most part without a return to life as usual. So there are many converging reasons to think about access to information and preparedness in these communities, and with the workshops we had an opportunity to address current, future, and long-standing communications issues.

Across the workshops, we learned about NYC residents’ communication challenges during Sandy and its aftermath, as well as equitable access to information generally -- especially the roles of different kinds of communication technologies, how information gets around in everyday life, and how that pattern changes in an emergency. Following are some of the main themes we heard about regarding communication in Sandy-impacted communities.

Theme 1. Connect offline hubs with the online world

Across the workshops, people talked about local community hubs -- well-known hangouts where people instinctively go for help and comfort -- and the unique role those spaces played during Sandy. These ranged from a well-known neighborhood neighborhood watering hole in Staten Island to churches in Long Island City and the South Bronx to a YMCA in Sheepshead Bay. In each case, these were places where people went during Sandy to seek out comfort, companionship, and information -- where they trusted they could find their neighbors and make plans to help the elderly, isolated, and sick in their communities. Many workshop participants saw value in the idea of adding communications infrastructure to these hubs in order to link the online and offline worlds. But they were also clear that online or digital resources would never replace physical hubs and face-to-face connections. Rather, they talked about linking these spaces with online resources like the Amazon registries used by volunteers during Sandy to log needs and gather donations -- and about the need to designate local people in advance to lead these efforts.

Participants saw offline networks as a fundamental part of resilient communications systems.

Theme 2. Work collaboratively to address past, present, and future challenges

Participants in all the workshops emphasized the importance of local leadership, along with physical hubs and connection points. Representatives of local advocacy and public housing tenant groups especially spoke about long-standing challenges related to poverty, lack of access, and legacies of inequality, and how these add to challenges around response and recovery. Many maintained that it is crucial to consult local leaders already working on issues related to poverty and opportunity in implementing any communications resilience planning, since these leaders have a sense of existing challenges and issues.

In Staten Island and Sheepshead Bay, which experienced devastating flooding, loss of property, and public health crises due to Sandy, residents emphasized the demands placed on local leadership and resource centers. Many residents in these areas feel they are still in response and recovery mode, and that moving toward a resilience framework could take attention away from critical and immediate needs. They stressed the need for communications tools to help support CBOs and small businesses that have shouldered much responsibility in their communities, and in some cases have not survived the crisis.

In the South Bronx and Long Island City, which had less critical flood damage, long-standing “digital divide” issues came into focus when discussing emergency communications planning. Residents insisted that any new infrastructure or intervention must address issues not only around emergency preparedness, but around everyday access to broadband service and computers, as well as digital literacy. They also pointed out that increasing digital access could help to address other pressures on their communities, from lack of employment opportunities to poor schools. In the South Bronx, many participants described a collective “cradle to career” impact framework that supports and coordinates the efforts of many groups across the borough, providing a holistic framework to improve outcomes. They stressed that emergency communications planning should speak to and support long-term goals informing this work.

Workshop participants in the Bronx focused on creating collaborative processes in building resilience.

Theme 3. Meet people where they are

A major finding of our workshops was that in many places, different communities using different communications methods live in the same places. For example, in Sheepshead Bay, Chinese speakers, Turkish speakers, and English speakers all live in the same neighborhood but share information differently, using different media like radio, newspapers, and flyers, in addition to limited digital media. Likewise, in almost every community, people of different ages use different kinds of communications platforms. Across the board, we found that a central challenge for information preparedness planning was coordinating a communications strategy among different groups with different communications styles.

This was true especially in places undergoing transformation, as in neighborhoods like Sheepshead Bay under development pressure, where long-standing tensions exist among longtime residents and newcomers. In these places, communications planning -- including planning for coordination across different language groups, platforms, styles, and offline hubs -- was seen as a relationship-building process that could bring added benefits for community organizing and cohesion. Every group we spoke to also stressed the importance of incorporating and linking among multiple communications modes and styles as a way of building local relationships.

Participants in the Queens community-based resilience convening discuss connectivity in the Astoria neighborhood.

Outcomes: Designing connections, relationships, and strategies

The learnings from these workshops are informing the work of New America’s new Resilient Communities Program, which helps communities and local leaders protect and improve assets, infrastructure, and systems to ensure availability, affordability, and fair access to food, water, sanitation, health, housing, transportation, energy, and communications – day-to-day and in an emergency. The Resilient Communities Program will use the specific findings from each mapping activity to inform our work with communities in Staten Island, Queens, the Bronx, and Brooklyn co-designing and building resilient community wireless networks as part of the RISE : NYC citywide Economic Development Corporation resilience initiative.

Meanwhile, the City is moving forward with its coordinated resilience planning, with convening power added by the Municipal Art Society. On September 29, MAS held an all-day resilience convening to help inform New York’s Phase 2 proposal to HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition. The City’s proposal, “Protect and Connect,” cites to the clear need for improved infrastructure and connection among storm-vulnerable New York neighborhoods, particularly in lower Manhattan. At the convening, many participants talked about just how integral community-based organizations have been throughout the Sandy recovery process. CBOs and community groups of all sorts, in turn, talked about the need to build resilient networks and strategies among themselves for communication, coordination, and self-organizing. Yet as trusted community groups and local organizations take on this essential role in building resilience, they also add a burden and a set of capacities to their existing work. Government agencies, philanthropies, and official response networks will need to recognize and support them.

Meanwhile, local groups have a range of options for communications preparedness: wireless networks like Red Hook WiFi are one kind of technology tool that can help communities become more resilient and prepared in an emergency, but there are many others, including neighborhood listservs and shared docs, SMS alert systems, and even guides on how to manage power and networking on devices. Communities can decide what kinds of technology are most useful for them and require the right level of effort and expertise for their own capacities. The important thing is to think now about communicating during an emergency, and plan ahead for how to reach out to each other and share information if and when normal systems fail. Experts have shown that relationships among people, and existing social support networks, are the bottom line for responding, recovering, and becoming resilient to emergencies and disasters. Communication systems -- high-tech, low-tech, and no-tech -- are just some of the ways in which those connections are expressed.

Download the "Every Community Is Resilient" collaborative mapping module.