Ryan Budget Brings Little New to the Table

Blog Post

Gage Skidmore / Flickr

April 1, 2014

Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI), chair of the House Budget Committee, this morning released his own fiscal year 2015 proposed budget. The budget, if the House adopts it, would serve as that chamber’s 2015 budget resolution, establishing spending and revenue targets for the upcoming fiscal years. (The Senate has already decided not to pass a budget resolution, so even if the House version passes, there will be no joint fiscal year 2015 resolution.)

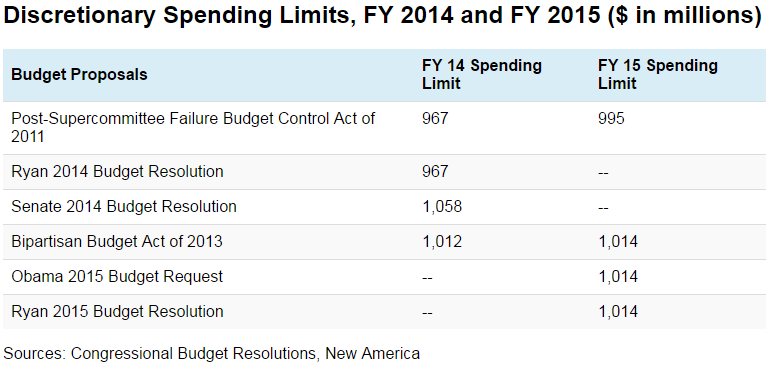

There are few differences between Ryan’s proposed 2015 budget and last year’s proposal, at least in terms of education policy. But there is one point worth noting: The Ryan budget abides by the overall discretionary spending targets he negotiated with Senate Budget Committee chair Patty Murray (D-WA) last year, passed into law through the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. That’s no surprise, given how involved Ryan was in creating the targets, but it does mean spending under his plan is well above the targets originally set by the Budget Control Act of 2011. And it means the Senate, which plans to use the Bipartisan Budget Act limits as well, will be exactly aligned with the House in terms of overall spending targets.

In fact, Ryan’s budget even complies with the defense/non-defense breakdown of spending agreed to in the Bipartisan Budget Act – in its first year, at least. Later years make significant cuts to non-defense spending and restore much of that funding to the defense budget. But Ryan’s commitment to sticking with those caps, even for just one year, could make the politics of passing appropriations bills in fiscal year 2015 simpler than it has been in recent years.

That doesn’t mean education programs are entirely in the clear. Because the Ryan budget proposal seeks to balance the budget over its 10-year spread, and sacrifices non-defense spending in later years in favor of defense spending, some education programs would see cuts. (Though it should be noted that, even if the House passes this bill, its provisions would have to become law separately through appropriations bills or other legislation also signed into law.)

Ryan’s commitment to sticking with the spending caps, even for just one year, could make the politics of passing appropriations bills simpler.

Most of the education provisions in the 2015 budget proposal also made it into Ryan’s 2014 budget – and in some cases, seem to be cut-and-pasted from last year’s version. Ryan would consolidate more than 50 workforce and training programs and a number of K-12 programs to eliminate bureaucracy and avoid duplication of federal efforts. He would "encourage innovation" in fields like online education and give renewed consideration to higher education data available to students.

Whereas last year, he proposed maintaining the then-maximum Pell Grant of $5,645 for the full 10-year budget window, this year he proposes maintaining the 2013-14 maximum award of $5,730. In both years, he proposed rolling back reforms that made Pell Grants available to more people (for example, resetting the family income at which families’ expected contribution is automatically zero). And as in prior proposals, Ryan’s budget notes additional changes that could be made to reduce the costs of the Pell Grant program, including a maximum income cap and making the awards unavailable to students who attend college less than half-time.

But changes to the Pell Grant program aren’t the hot topic they used to be. Given that the Pell Grant program is actually expecting another, larger surplus in 2015, it’s unlikely Congress will spend much time pecking around its edges, so those proposed reforms probably won’t see much action in Congress this year. Moreover, these reforms aren’t necessarily that significant. Depending on the level at which he set the income line, the Congressional Budget Office estimates it could save about $700 million over 10 years – a relative pittance in a $35-billion annual program. The elimination of less-than-half-time student awards, CBO estimates, would save about $300 million over 10 years; again, that’s relatively little given the size of the program.

Ryan also proposes changes to the Return of Title IV Funds requirement – including requiring students to attend classes for longer before being eligible to withdraw from school without debt owed. That, he says, will make it more likely students finish school – and less likely the program will be used for fraud. And he would eliminate the administrative fees schools receive under the campus-based aid programs, although he doesn’t propose any changes to the widely derided funding structure of those programs.

On the student loan side, Ryan would also make a few changes to the student loan program. He would eliminate the interest-free benefit for undergraduates, whereby students with Subsidized Stafford loans don’t begin accruing interest on those loans until they leave school. And he notes, as New America has on many occasions, that income-based repayment (IBR) in its current form may overly benefit graduate and professional students. Instead, he says, IBR should be repealed and reformed to better target its benefits before expanding it.

Finally, one of the most significant–albeit least understood–reforms would restructure the way the government calculates the costs of the loan program altogether. Currently, the cost calculation excludes an added cost for the “market risk” of lending to borrowers. Also included in last year’s proposal, Ryan notes that the House Budget Committee has already passed a bill to switch to “fair value accounting” – not just for student loans, but for federal housing and other government lending programs, as well.