New Report Shares Lessons on Pre-K Teacher Compensation Parity Policies

Blog Post

Oct. 30, 2017

“A labor of love,” is often a term associated with being an early childhood educator. While working in pre-K does require an affinity for playing with young children, there is a popular misconception that pre-K teachers are simply babysitters. Early childhood educators do have the pleasure of leading storytime and guiding imaginary play, but they also have the complex and challenging responsibilities of building children’s language and literacy skills, introducing foundational mathematic and scientific concepts, developing their critical thinking, and encouraging their social-emotional development---all through an immense amount of love and patience. While teaching pre-K is indeed a labor of love, it also needs to be a labor of adequate pay.

Recognizing that low compensation can impact pre-K program quality, more states are working to provide compensation parity among pre-K and K-3 teachers in state-funded programs.The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) in collaboration with the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), recently released Strategies in Pursuit of Pre-K Teacher Compensation Parity: Lessons From Seven States and Cities, a new report examining state and local compensation parity policies for pre-K teachers in different education settings. This is the third part in a series on pre-K parity.

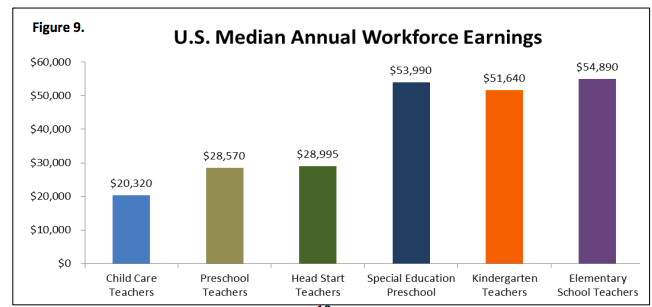

Data show that salaries for pre-K teachers are significantly lower-- sometimes less than half-- of those teaching children five years or older. As a nation, there is growing recognition that early childhood education is not only valuable, but critical to the development of young children. The education qualifications and credentials for pre-K teachers have started to catch up with the research in some places, acknowledging that these teachers need specialized knowledge and skills. Even when their qualifications match K-3 teachers, early childhood teacher salaries and benefits remain lower. As shown below, the median annual wage for pre-K teachers in the United States is only $28,570, as compared to an annual wage of over $50,000 for K-3 teachers. Pre-K teachers are earning near poverty level wages; many teachers working with infants, toddlers, and pre-kindergarteners receive public assistance.

Source: Department of Education

The CSCCE and NIEER report defines compensation parity as “salary and benefits for equivalent levels of education and experience, adjusted to reflect differences in hours of work, and including payment for non-child contact hours (such as paid time for planning).” To show diverse parity strategies, the report analyzed state policies in Alabama, Georgia, New Jersey, Oregon, and West Virginia. It also explored local parity policies in New York City and San Antonio. These states and cities are making gradual efforts toward full compensation parity. Though still in the early stages, some of these policies may have the potential to serve as models for other states.

The examined states and cities are using a combination of strategies. In New Jersey, for example, state law requires compensation parity for all pre-K teachers, regardless of education setting in two out of the state’s three pre-K programs. Parity includes paid time for planning and professional development equivalent to that of K-3 teachers. Under this law, pre-K teachers in larger school districts also receive benefits equivalent to K-3 teachers.

Oregon attempted requiring parity, specifying that “target salary requirements shall be comparable to lead kindergarten teacher salaries in public schools.” Legislative language has been weakened, however, allowing regional pre-K administrators to instead set “practicable” salary guidelines for pre-K teachers comparable to lead kindergarten teacher salaries in public schools. While this a step in the right direction, it likely means there will be more progress on parity in some settings, but not statewide.

States’ and cities’ approaches to determining parity also vary. Some use median kindergarten salaries as a benchmark for pre-K teacher salaries, while others place pre-K teacher compensation on the same salary scale as K-3 teachers. In Alabama, for example, pre-K teachers and K-3 teachers have the same starting salary, but the methods for ongoing salary raises differ.

It’s not surprising that states with better funded pre-K programs are generally the states with compensation parity policies in place. San Antonio, for instance, moved beyond full parity and provides pre-K teacher compensation higher than the pay of local K-3 teachers.This is partly because the city raised its local sales tax and the pre-K programs in the city receives contributions of state education funds from many of the local school districts.

State and city pre-K program administrators interviewed for the report commonly referenced the differences in public funding for early childhood education as a constant challenge in their efforts to reach pre-K compensation parity. Levels for funding pre-K vary across the states and cities in the report. Alabama uses a combination of federal grants and the state education trust fund. Georgia uses education lottery funds as a pre-K funding source. General state funds are used in Oregon, while New Jersey uses state education funds. San Antonio and New York City incorporates local sales tax and state pre-K funds. West Virginia uses a combination of state pre-K funds (including multiple grant sources), city tax levies, and a federal pre-K grant.

State and city pre-K program administrators also noted the persistent challenge community-based providers face in meeting the cost of increasing compensation, specifically benefits, for pre-K teachers. It is explained in the report that “because pre-K funding is limited to specific classrooms within a program and because other classrooms likely rely on lower funding amounts from parent fees or child care subsidies, providers may be reluctant to increase salaries only for certain pre-K teachers, while being unable to increase salaries for other teachers, some of whom may be doing equivalent work, have equivalent qualifications, or may even have significantly greater tenure and experience, yet earn much less.” Parity in benefits and salaries would require providers to offer the same benefits package for pre-K teachers in a small center as they would in a large elementary school, which presents a challenge when adequate funding is not available.

While approaches and policies toward pre-K compensation parity are relatively new, pre-K administrators already reported positive benefits. According to the report, in both New York City and Georgia, proposals around compensation parity for certified pre-K teachers are influencing discussions on improving compensation for infant and toddler teachers. In New York City, the city’s child care union successfully negotiated compensation parity among certified early childhood teachers in community-based settings and those teaching outside of pre-K. Alabama pre-K administrators reported that their kindergarten teachers are increasingly becoming interested in teaching pre-K, rather than the other way around. Many of the administrators are optimistic that developing new compensation levels will result in lower teacher turnover rates and higher quality pre-K programs in the future.

*11/7/2017: This post has been updated to reflect a change in source for the table and terminology.