Duncan's Record in Chicago

Blog Post

Feb. 18, 2009

When Arne Duncan was tapped to become the new U.S. Secretary of Education, early-education advocates praised the choice. (We, too, were pleased.) Media reports and interviews with Duncan's colleagues, not to mention Duncan's own words, have signaled his strong grasp of the importance of early education. Now everyone wants to know: How will this translate at the federal level?

Previous: All Eyes on Illinois…

Today: Duncan’s Record in Chicago

Next week: Q-and-A with Barbara Bowman

Next week: What’s been cut

On Tuesday we showed how Illinois's state-wide approach provides a potential framework for increased federal involvement. Today we look at Chicago, where Duncan was chief executive officer of the city's public school system from 2001 to 2008. Continuing the work of his predecessors, Duncan baked early education into the public school system, and the number of children enrolled in publicly funded programs for 3- to 5-year-olds increased by several thousand over the past several years to more than 30,000 as of last month. (The number rises to nearly 39,000 if you count infants and toddlers.)

But Duncan didn't make these cookies from scratch. He started with a ready-to-mix box of ingredients and many batches already in the oven. He was blessed with the support of a mayor and governor who believed in early childhood funding; a new state-wide funding stream called Preschool for All; a band of fiercely devoted advocates for early childhood with national reputations; an internationally renowned research center for early childhood -- the Erikson Institute -- in his own backyard; and decades of vetted research showing the effectiveness of Chicago's Child-Parent Centers.

What's more, Duncan had Barbara Bowman, co-founder of the Erikson Institute. Duncan appointed her to run C.P.S.'s early childhood programs in 2004. "Bowman was someone who Arne really relied on to set the agenda and carry the ball," said Cornelia Grumman, executive director of the First Five Years Fund, a project of the Chicago-based Ounce of Prevention Fund.

The combination of Bowman's vision and the flexibility of the state's Preschool for All program has worked well so far for Chicago's early childhood system, though not everything was perfect at first. In 2004, a Chicago Tribune editorial chastised Duncan for not using state pre-K money for its intended purpose. He quickly changed course. According to an opinion piece in the Tribune a few weeks later from child advocates, Duncan "restructured the budget to ensure that all new preschool dollars are indeed spent for preschool." Today, preschool advocates and Grumman - who, in fact, was a member of the Tribune's editorial staff until last year -- sing Duncan's praises for "getting it" on the importance of early learning. Preschool programs across Illinois have received high marks for quality from the National Institute for Early Education Research. And David Kirp, a public policy professor at the University of California at Berkeley, focused on several of Chicago's preschool centers in his book, The Sandbox Investment: The Preschool Movement and Kids-First Politics, calling them "models of good practice."

An examination of Chicago's system shows how Duncan may envision change on a federal level. Observers say Duncan is a pragmatist, not unlike his friend President Obama. He is known for having a philosophy of "letting a thousand flowers bloom," giving the go-ahead to new projects that show signs of working and keeping options open for innovation with outside organizations. "That's been the general approach: private-public partnerships and evidence-based efforts," Grumman said.

Early childhood efforts in the Chicago public schools include:

- Enabling 27 preschools to run a third shift, from 3 to 5:30 p.m., to accommodate more families

- Using Title I funding for some preschools, continuing a strategy that was in place long before Duncan's arrival. (This approach was hailed in a recent Ed Week piece by Yale psychologist Edward Zigler, and we've pushed for it too as an innovative way to improve No Child Left Behind)

- Embedding tuition-based preschool programs in the public schools to encourage middle-income families to become part of the school community

- Including independent, community-based centers in the school system's early education network

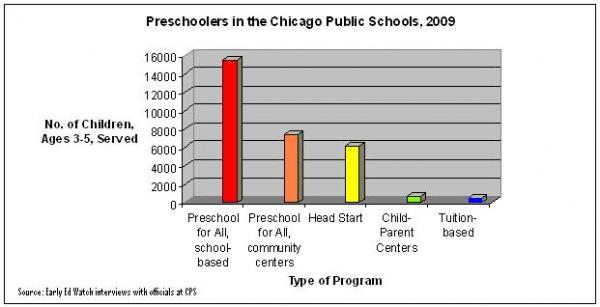

But probably the strongest example of this "let a thousand flowers bloom" approach is the structure of the C.P.S. early childhood program. Families have multiple centers to choose from -- an emphasis on variety that could be a harbinger of how Duncan will proceed on a national level. Parents in Chicago have the option of enrolling their children in one of four types of preschools under the C.P.S. umbrella: "Preschool for All" centers at the public schools or in facilities run by community providers, Head Start centers and Child-Parent Centers. Each of these three provides free tuition to low-income families. The daily "Preschool for All" programs are 2.5 hours long; other centers offer half- or full-day programs.

Middle-income families can choose to enroll in a C.P.S. preschool, too, by paying around $9,000 a year for the full-day, tuition-based programs. Paula Cottone, deputy chief in C.P.S.'s early childhood office, said that Duncan established these options to encourage middle-income families to get involved early in the public schools. (For all of these choices, parents are invited to use a locator site with interactive maps to find programs close to their homes or offices.)

Bowman's job is to keep a handle on each of these four programs (five if you count the two Preschool for All types), ensuring they measure up on quality. With community-based providers, this is particularly difficult because each center comes with its own traditions for hiring staff members and its own philosophies about working with young children. But Bowman has instituted requirements that ensure these providers meet Preschool for All's criteria for quality in order to get extra funding from C.P.S. and be included in the school system's early education offerings. The Preschool for All law mandates that every lead preschool teacher have a bachelor's degree with training in early childhood. (For more on Bowman's strategies to improve quality, watch for our next blog post in the series.)

Arthur J. Reynolds, a professor of education and human development at the University of Minnesota who has spent years studying Chicago's early childhood systems, says this oversight from the school district is "probably far ahead of what a lot of cities and states do."

"They tried to build a system that has clear lines of authority but lots of flexibility," Reynolds said.

On the federal level, of course, early childhood funding and authority will look quite different. For one, Head Start is overseen by the Health and Human Services Department, so the quality of Duncan's relationship with whomever is appointed to run H.H.S. will have bearing on how early learning programs take shape.

Note too that Duncan didn't do everything all at once in Chicago. Supporters say that he wanted to ensure first that programs could be kept going once they were started. "That's a key point that Arne and Barbara are on," said Jerome Stermer, president of Voices for Illinois's Children and newly appointed chief of staff to Illinois Gov. Quinn. "You have to grow programs that you can sustain." He added: "The idea is not to say, three years later, ‘sorry we're going to now fund another program.'|"

In fact Duncan was criticized by the Tribune for dragging his feet in the first six months as C.E.O of the Chicago public schools. He responded in a letter to the editor in December 2001, assuring readers that "school reform is well under way." If we can predict anything, it's that on the national front, he may face the same impatience.